1 "The Dialectic of Civilization" Michael Becker California State

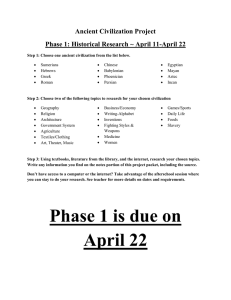

advertisement

"The Dialectic of Civilization" Michael Becker California State University, Fresno Abstract: Civilization is rooted in lies, at both a simple, prosaic and complex, philosophical level. Ideas of a "fall from a golden age" in western political theory, from Plato to Rousseau, serve as cover for large scale crimes by which civilization extends itself and eliminates primitive cultures. But these lies do more. They distort the image of the primitive in such a way that attainment of the highest civilized aspirations seems to redeem civilization and recuperate lost, allegedly primitive values in a higher form. In fact, these aspirations are unattainable. The result is a "double-bind" that engenders widespread social pathologies. Anarcho-primitivism rejects the terms of civilization and seeks wholeness through a "future primitive." "Deception is a state of mind, and the mind of the state." James Angleton This essay concerns the relationship between the civilized and the primitive. Primitive cultures are rooted in myths; civilizations are based on lies. The lies that concern us disguise the relentless violence by which civilization displaces and then eradicates the primitive. These lies are of two sorts, both dialectical in form. The more prosaic, political dialectic constitutes an erasure of the primitive. This suffices for a basic political or historical account of the civilized world. But it does not suffice for generating the necessary frenzied pace with civilization, especially modern, western civilization, drives itself forward. A second, more refined dialectic incorporates a distorted depiction of primitives and an equally distorted depiction of civilization, a contradiction that appears to be resolved through "higher culture." Civilization wants it all; mostly it wants to redeem something that it has to destroy in order to exist, the primitive. Necessarily then it must deceive itself both about the primitive and its own highest meanings. Such deception is a key constituent in civilization's furious violence. Genocidal destruction threatens to betray civilized man's idea of himself. A higher-order dialectic must be created, one which, in a moment of ostensible transcendence, can re-inscribe what was allegedly lost. But redemption never actually arrives. The attendant despair of irredeemable loss and the (non)recognition of irresolvable contradictions are motive forces of a conquest that founds civilization and never ceases (at least until civilization implodes). Needless to say, the dialectic of civilization resists disclosure, hence the difficulty of what is set out here. A "negative dialectics of civilization" might be a more appropriate title for this endeavor. Adorno claims that "whatever truth concepts cover beyond their abstract range can have no other stage than what the concepts suppress, disparage and discard." Moreover, the sublimation of concepts gives unconscious sway to the ideology that the not-I, l'autrui, and finally all that reminds us of natures is inferior, so the unity of the self-devouring thought may devour it without misgivings. This justifies the the principle of the thought as much as it increases the appetite. The system is 1 the belly turned mind, and rage is the mark of each and every idealism.1 What better exemplifies a dialectics of hidden rage than the deceptions in western political theory? Gone is the violence that wipes out the only sustainable cultures the world has seen. In its place arises the mendacious notion of a "fall" from the golden age, as if it is is those who commit the crime that are to be mourned. Moreover, the conditions in this alleged primordial state of nature are only reflections of the civilized mind misrepresented to itself. To be sure, by that noblest of instruments, civilized reason, we will reintroduce, at a higher level, the lost harmony of the golden era. In reality, those committed to civilization are barred from a return to the primitive, and the promise of its return in a conscious and complete form is void. What is intended here, then, is a brief analysis of both the prosaic and the philosophical instances of dialectical reason. The place to begin is at home, a violent crime scene wherever you live. The Dialectic of Erasure Where I live, in the heart of the Great Central Valley of California, there is a plaque in front of the County Courthouse dedicated to the valley's first settlers. It reads: "they made the desert bloom." The plaque is both historical and relates to law, hence the courthouse locale. The dialectic it conceals is, obviously, temporal in its divisions. First, there is a desert; it is devoid of life, a barren place. In and of itself it cannot be thought of as first in a sequence because, until it is discovered, it exists outside of time. Only upon discovery does its potentiality avail itself to the discoverer and thus become an initial moment. Until then it is a desert, not just of unused land, but of any conceivable purpose or meaning. The tabula rasa of the desert cannot become a moment dialectically until it shows itself as potentially meaningful, i.e., economically valuable as a source of commodities. The past tense "made" encompasses the relentless work of the settlers who, through their labor, challenge the desert to release its potentiality into actual productivity.2 This work constitutes the antithesis to the fallow nature of the desert as such. As opposed to the meaningfulness of work, the desert strikes one as almost perverse in its inert meaninglessness.3 The desert as mere presence provokes its opposite, the furious action of transformative laboring. The introduction of labor makes the desert "real" in the sense that it creates a moment in time. Civilized rationality can only exist in rationally measured time, and the desert in its opposition to labor becomes rational and real. This is the compulsion of the dialectic; it rules in all science and technology. First nature is a provocation. 1 Theodore W. Adorno, Negative Dialectics, trans. E.B. Ashtom, (New York: Continuum, 1973), pp. 22-23. The totality of this mania is perhaps nowhere better expressed than in Pascal's, Penseé 347: “if the universe were to crush him, man would still be more noble than that which killed him, because he knows that he dies and the advantage which the universe has over him; the universe knows nothing of this. All our dignity consists, then, in thought. By it we must elevate ourselves, and not by space and time which we cannot fill. Let us endeavor, then, to think well; this is the principle of morality.” If primitive cultures teach us anything it is that thinking well and being moral are predicated precisely on an awareness of our dependence on one another and on the natural world of which we are a part. It is on the basis of the illusion of elevating ourselves above the entire universe, especially through thought, that humans commit monstrous crimes. 2 See Heidegger's discussion of "challenging forth" and "standing reserve" in Martin Heidegger, "The Question Concerning Technology," translated and with an introduction by William Lovitt, (New York: Harper Row Publishers, 1977) 3 It is common in settler accounts of the Central Valley to hear the Europeans marveling at the beauty and abundance of the land and, simultaneously, to protest that the Indians are letting it all "go to waste." 2 But Now!, the plaque suggests, we are the recipients of the settlers' undaunted labor; we are living in the luxurious blooming of the desert. The flowering of the desert constitutes the synthesis of the potential fertility of the desert with the hard labor of the settlers who brought the desert to life. This eternally fecund moment replicates the eternity of the desert but differently. Through the rationality of the dialectic we come to know that the eternal moment of blooming occurs within the rationality of successive historical stages. The desert can now be grasped as materials or resources ready to hand for laboring. Laboring, in turn, must be constantly repeated to deliver the bloom, not to mention the fruits. The timelessness of the synthesis, the perfected moment of scientific and technological productivity, depends upon the constant repetition of transformative labor: the desert turns into product ceaselessly. Now is utopia, always, this moment, and everywhere. As it is reality fulfilled, there is no possibility of anything rational subsisting outside of the endless repetition of production and consumption; it is this perfection that confirms one's identity as a legitimate recipient of a desert turned cornucopia. This crude version of the dialectic of civilization provides a prosaic, if perverse, accounting of European conquest in central California. It shows up in such mundane places as courthouse plaques and presidential speeches.4 It is simultaneously more directly honest about the nature of civilization and, in equal measure, less enlightening than the refined and ultimately more significant versions appearing in philosophical and religious works. The plaque characterizes the place of the settlers' arrival as a "desert." The phrase obliquely memorializes the erasure of the original people, plants, and animals of the Great Central Valley. Simultaneously it inverts biological reality. This place, actually, once was what might now be termed a "biodiversity hotspot." There were huge Tule Elk herds, pronghorn antelope herds, deer herds, innumerable grizzly and black bears, and wolves. The largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi--Tulare Lake--supported countless migratory and native birds, shellfish, and wild rice, while the rivers "teemed" (the word used so frequently in settler accounts) with salmon, steelhead, and other fish. First settlers give accounts of miles wide swaths of different colored wildflowers carpeting the valley in springtime. In, amongst, with, and around it all, the valley and foothill Yokuts Indians "tended the wild," in M Kat Anderson's apt phrase.5 Their interactions in the world of which they were a part were designed both to feed, shelter and clothe themselves and to increase the abundance of the lifeworld. Archeologists indicate a continual human presence for onehundred thirty centuries. In ecological terms what once was a paradise of life has now become a wasteland of agri-industrialism and suburban tracts. The dialectic of erasure is an inversion of reality. Every political truth obscured within the prosaic mode of the dialectic of civilization (the plaque) is a Titanic irrationality which proves itself, first, through the relentless slaughter of those to be subjugated. The indigenous are constantly present to the civilized by their absence. Erasure is the means by which the crime is to be denied and leveled off in a technocratic and utilitarian morality that exchanges the civilized subjects' servility for a delivery of the material goods. "Every society is founded on a crime committed collectively, but the deed (the anguish and revulsion it provokes) is subsequently denied by those who most benefit from it. Complicity and 4 Perhaps a more common version acknowledges the existence of indigenous peoples as an obstacle to the inevitable and undoubtedly preferable path of civilization. But the "philanthropist will rejoice" that an "unhappy" and "ill-fated" race will be removed to new lands where "under the paternal care of the government" they will eventually "share in the blessings of civilization." Erasure of the primitive occurs when the antagonism between savage and settler is resolved through all sharing in civilization. Andrew Jackson, "Farewell Address," http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=67087#axzz1p5s8yzKx 5 Anderson, M Kat, Tending the Wild, (Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 2005). 3 denial are constitutive of morality, whose concern for utility is merely there to suture the wound."6 Analytically, disclosure of the erased violence in the prosaic dialectic is necessary as a reminder of the systematic violence inherent in civilization. It reawakens "anguish and revulsion." During the gold rush, towns across California paid for Indian scalps, and the state government reimbursed local governments for the cost of hunting down Indians. The services of displaced, vagrant Indians could be auctioned off. Whites were permitted to compel Indian children to work for them, and vigilantes kidnapped Indian children to be sold them as "apprentices." Of course, there also occurred wholesale slaughters of Indians as at Campbell Mountain near where I live and where hundreds of men, women and children of the Choinumni band of Yokuts were murdered in cold blood.7 As Thomas Packenham has noted "The attitude of...all Europe was tabula rasa, terra incognita, here was a place that was sort of a no-man's land; in other words we can create our own states there and we're going to bring order and civilize them; always the word 'civilize' was used whatever you were actually doing, whether you were shooting them, you were civilizing them."8 To begin to grasp the seemingly irreconcilable contradiction between civilized, rational order and mass murder it will be necessary to consider a higher order dialectic. On this level the primitive is also erased but via a distortion. It seems as if the primitive serves as a kind of rebuke to the civilizing mission. There is something about the primitive that must be exposed. It must be forced to reveal itself to the civilized in a way that will allow the civilize to incorporate it by mastering it. Civilization must prove to itself that whatever is primitive and alien is merely aberrant and will be corrected and transformed into rational reality through the civilizing mission. This will to annihilate the other through its incorporation can be seen in the non-human as well as the "sub-human." Consider Baudrillard in his discussion of animals in Simulacra and Simulation. Regarding the various forms of animal use and abuse, specifically in laboratories, he remarks Animals must be made to say that they are not animals, that bestiality, savagery--with what these terms imply of unintelligibility, radical strangeness to reason--do not exist, but on the contrary the most bestial behaviors, the most singular, the most abnormal are resolved in science, in physiological mechanisms, in cerebral connections, etc. Bestiality, and its principle of uncertainty, must be killed in animals.9 The comparison of primitive peoples to animals, the longstanding claim that their languages were indistinguishable from animal grunts and cries, is obviously familiar. But what are we to make of the displaying of primitive peoples in zoos, like animals?10 It is possible that the mass killing of the 6 Sylvere Lotringer in George Bataille, On Nietzsche, trans. Bruce Boone, St Paul, Minnesota: Paragon House, 1994), p. xii. 7 The mountain is named after the officer who led the slaughter and who later became a prominent local citizen. Its real name is Waitoki Mountain named for one of the last, prominent chiefs of the Choinumni. 8 Packenham, Thomas, Racism: A History, DVD, directed by Paul Tickell (London: BBC, 2007) 9 Jean Baudriallrd, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. Sheila Faria Glaser, (Ann Arbor, Michigan: The University of Michigan Press, 1994), p. 129. 10 Sixty African people were put on display in a mock African village in the "Palace of the Colonies," part of the 1897 International Exposition and later incorporated into the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tevuren, Brussels, Belgium. Similarly, the "last wild California Indian," Ishii, who was the last remaining survivor of the Yana people of northern California, was put on display on a regular basis at the University of California Berkeley Museum of Anthropology in 4 primitive is related to a desperate bid to eliminate a strangeness that simultaneously cannot be, yet must be, accounted for in the imperialistic bid. Premised, as civilization is, on certainty, the confrontation with the irreconcilable in primitive culture, as in non-human animals, must result in annihilation of the other. But this annihilation must be justified within the rational schema of the civilized. The Paradox of the "Fortunate Fall" Civilized people neither labor nor soldier under the banner of erasure. There obtains among civilized people a peculiar and pervasive nervous energy and anxiety that drives its adherents forward in the relentless, expansionary work of civilization. A different sort of dialectic is necessary for generating this civilized anxiety, though this too centers on an opposition between the primitive and the civilized. The trick of civilization is to establish an alleged fundamental separation from nature and then to argue that the principles of civilization are nonetheless natural. Our separation is our salvation. Arthur Lovejoy coined the apt phrase a "fortunate fall" to describe this phenomenon. In the Twelfth Book of Paradise Lost Adam reflects on the fate of humankind as described to him by the archangel Michael. Much of this history records the travails unfolding from the first sin. But in the end, with the second coming and final judgment, the faithful inherit a paradise even greater than Eden. "O Goodnesse infinite, Goodnesse immense, That all this good of evil shall produce, And evil turn to good--more wonderful than that which by creation first brought forth Light out of darkness! Full of doubt I stand, whether I should repent me now of sin by me done or occasioned, or rejoice much more that much more good thereof shall spring--to God more glory, more good will to men from God--and over wrath, grace shall abound."11 The paradox of the fall, as Lovejoy eloquently puts it, is that it "could never be sufficiently condemned and lamented and, likewise, when all its consequences were considered, it could never be sufficiently rejoiced over."12 But as "deception is the mind of the state" and as the prosaic version of the dialectic illustrates, the "fall" involves no sort of choice. Those warped by civilization slaughter those who aren't. The consequences are never fully considered, either in terms of the genocidal crime that wrought the destruction or of what has actually been destroyed.13 The effect is not paradoxical but dialectical, though the synthesis never occurs. The promise of deliverance from the first sin is a redemption that always fails. Among political theorists, the contradiction inherent in the fortunate fall was forcefully presented in Rousseau's famous opening to the "Discourse on the Origin of Inequality, "Man is born free and everywhere is in chains." Rousseau makes the move back toward civilization by arguing, first, San Francisco. 11 Arthur O. Lovejoy, Essays in the History of Ideas, (New York: Capricorn Books, 1960), p. 277. 12 Ibid., p. 278. 13 One is reminded here of the reflections of Black Elk on the heinous slaughter by the U.S. 7th Cavalry Regiment of hundreds of Lakota camped at Wounded Knee Creek on December 29, 1890. "I did not know then how much was ended. When I look back now from this high hill of my old age, I can still see the butchered women and children lying heaped and scattered all along the crooked gulch as plain as when I saw them with eyes still young. And I can see that something else died there in the bloody mud, and was buried in the blizzard. A people's dream died there. It was a beautiful dream.... the nation's hoop is broken and scattered. There is no center any longer, and the sacred tree is dead."Black Elk, Black Elk Speaks, edited y John Neihardt (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1988), p. 241. 5 that a return to primitive existence is impossible. The long development of civilization, especially in the way property has corrupted innate self-concern and empathy, has allegedly so altered the nature of man that the option of a return to simplicity is off the table. Second, Rousseau claims that rational man can invent social institutions (the General Will) that reclaim and surpass the original, unconscious freedom and social solidarity of savages. There is no going back, and who would want to? We will have something superior. These are the two basic catechisms of life under the Law; they show up almost without exception in the history of political ideas. Like other noted social theorists Rousseau implants in his conception of the primitive certain conventions which are actually facets of civilization. They falsify the natural side of the dialectic. In Rousseau's case, he posits two allegedly innate traits that are, in fact, paradigmatic of modern civilization: "a faculty of improvement" and an isolated, egoistic conception of the individual.14 In the formation of the General Will, each participant must express his own views in an entirely direct and unmitigated fashion and then accept without question the determinations of the public vote. The primitive is allegedly surmounted, then, by raising up and completing a trait--atomistic individualism-that is not primitive at all. Plato, does this in his "Republic" by asserting that division of labor, an innate desire for luxuries, and complex, monetized trade relations are part and parcel of every social group. They are not. The schemes Plato develops for locking individuals into immutable social classes does not refine and lift up original, unconscious harmony among separate classes. Class division is instead integral to the extreme social stratification in civilized society. In the Second Treatise Locke counterfeits natural existence by insisting that the labor theory of property acquisition is natural. It is not. The conception of one's body as an instrument of labor power, owned by oneself and the idea that intermingling one's labor with nature creates an exclusive, individual entitlement to private property are quite at odds with primitive communalism. It is, instead, a necessary facet of a labor commodity market under capitalism. This falsehood of the dialectical opposition between city and nature in western political theory is reinforced by sanctifying the move to civilization. Thus, the other side of the dialectic is similarly distorted. In cases like those of Plato, Locke, and Rousseau, there is the same contrived and paradoxical fall from primitive grace found in Milton (or, indeed, in the Eden story in "Genesis"). In Book II of The Republic, while discussing the formation of communities, Glaucon chastises Socrates for his depiction of humans in primitive villages, communities "fit for pigs." They lack luxuries--civilized people are "accustomed to lie on sofas, dine off tables, and they should have sweets and sauces in the modern style." "Yes," says Socrates, now I understand: the question you would have me consider is, not only how a State, but how a luxurious State is created; and possibly there is no harm in this, for in such a State we shall be more likely to see how justice and injustice originate. In my opinion the true and healthy condition of the State is the one which I have described. But if you wish also to see a State at fever-heat, I have no objection. For I suspect that many will not be satisfied with the simpler 14 There are no instances that I know of, either from anthropology or archaeology, of humans living as isolated individuals. As for a "faculty of improvement," consider Raymond Firth's Primitive Polynesian Economy. The Tikopia show no particular inclination toward technological innovation. Their view oth of "natural resources" and of technique is governed by longstanding social and ceremonial beliefs and practices. It is the maintenance of a stable social order and world view which is paramount and which would, indeed, be threatened by technological development,. See chapter three, "Knowledge, Technique, and Economic Lore" in Firth, Primitive Polynesian Economy, (New York: WW Norton, 1965). 6 way of Life [emphasis added].15 It is Socrates' "opinion" that the primitive village is the "true and healthy" community. Plato's use of the word doxa here cannot be accidental when the entire purpose of his dialectic is to move from the uncertain ground of opinion to absolute knowledge. It is only through civilization that the possibility of coming to know the Form of Justice and the ultimate Form of the Good can be realized. This is precisely how the contradiction between simplicity and luxury, justice and injustice, is to be resolved not to mention its paradoxical payoff. Since coming to know the Form of the Good is the pinnacle of human existence, civilization must be a natural prerequisite. It seems obvious that Plato cannot regret that which he depicts in a priori terms. In comparison with other social theorists, Plato is uncharacteristically blunt about the immediate impact of the transition to civilization: the disintegration of an originally harmonious community, a general decline in people's health, and the need for a professional military to acquire more territory for the fevered state. This heightens the tension between the primitive and the civilized and thus raises the stakes for what civilized rationality must deliver. A new leadership class of philosopher kings will be necessary whose aptitude for dialectical reason can grasp, intellectually, the sublime world of the forms, its pinnacle the Form of the Good. Social harmony, in its purer abstract form, can be grasped perfectly by the rational mind. Coupled with longstanding political practice the Guardians will devise the necessary rules and political lies that will check the soldiers and workers and bring social harmony, in its perfection, down to earth. Plato's account is a fake anthropology inasmuch as the entire point is to see how a polis comes into existence. There is no consideration of anything human outside of law and formal justice. In this sense, Plato's too is a dialectic of erasure. But by confounding the development of the polis with an anthropological tracing of any and all meaningful human development, Plato distorts the primitive. His oracular account of the form of the Good merely reinforces the actual impossibility of attaining justice in an inherently unjust social formation. Perhaps Plato's mock-tragic sense of civilization as a fall from grace is also directed at those benighted enough to believe that the primitive is actually preferable to civilization. This would almost certainly be targeted at the anarcho-primitivists of his day, the Cynics. But Plato is wrong. Humans are not designed by nature to fit a preordained system of division of labor and monetary trade; the shift to civilization is not an inevitable characteristic of being human; and Plato's theory of forms, not to mention his theory of Justice and the ideal state, does not even remotely recuperate the inherent social solidarity of the original, "true and healthy" community. The dialectical tension between the civitas and nature is deepened and strengthened through the depiction of a paradoxical fall from natural grace. In the modern era this is achieved in the use made of a state of nature, particularly with regard to property. The paradigmatic case is that of Locke's "Second Treatise." The pseudo-anthropological rendering of the primitive involves the allegedly natural origins of property. Nature is originally common to all. But since the body is self-owned property, the mixing of one's bodily efforts with nature creates an individual and exclusive right of private property. Acquisition of property is only limited by the degree of labor one can perform, the spoilage of that 15 Plato, The Republic, translated by Benjamin Jowett ( New York: Anchor Books, 1973), p. 57. A state at "fever heat" is among the most honest depictions of civilization you will find in the western canon; it conveys the delirious intensity and sickening pace of modernity. Only a student of Socrates could present such an ironic portrait of the polis. 7 which is removed from nature, and the sufficiency of land and natural resources for others. The invention of money and its tacit acceptance as a medium of exchange, Locke contends, is rational. It facilitates trade and thus access to the conveniences of life. Yet, because it also allows for the acquisition of unlimited amounts of property, money is simultaneously depicted by Locke in Biblical terms of original sin. "This is certain, that in the beginning, before the desire of having more than one needed had altered the intrinsic value of things, which depends only on their usefulness to the life of man...each one of himself [had] as much of the things of nature as he could use [with] the same plenty...left to those who would use the same industry."16 Life in a state of nature is initially marked by "peace, good will, mutual assistance and preservation." With money comes greed and property inequality; these create conflict and the need for a state to adjudicate property disputes. As with Plato, remorse at the fall is fake. The achievements of civilization more than make up for the loss of primitive innocence. Locke, again like Plato, erases the actual crimes that found civilizations and depicts the Fall as a choice involving unintended consequences. In Locke's case the fall is compensated for by the superabundance which investment of money in land allows. Money does not spoil, allows for wage contracts to purchase others' labor, and increases productivity indefinitely. "In the beginning" when all was America, people were few and land was plenty. There was unlimited enjoyment in fulfilling simple needs and wants. Use value was the sole basis for judging worth. But money ended the idyll of the original state. A state of original abundance soon came to entail a zerosum game. Still, Hobbesian war is averted without a totalitarian state because an infinite variety of wants are supplied by an infinitely expanding, rational and productive process. References to a transcendent Law of Nature help to cover the gap between the primitive and those rights still retained under the state. Moreover, they are useful in combating the primitivists of his era, the radical Levellers and Diggers of the English Revolution who proclaimed the retaking of private landholdings as a natural birthright. But in reality Locke's political thought is straightforwardly materialistic: for those who work hard, "the rational and industrious," that is to say the directors and investors in joint stock corporations, the abundance and variety of material pleasures in civilization more than make up for the loss of primitive equality and freedom. The world is theirs by legal right, founded in a social contract among property holders; state coercion and disqualification from political participation exist for the "covetous and quarrelsome." While Rousseau sees Locke's social contract as morally bankrupt, he does not, as noted, propose a return to the primitive. The healthy self-love of the savage is irrevocably lost. Vainglorious self-love, amour propre, develops in tandem with civilization and especially with property. But Rousseau too sanctifies civilization by arguing that reason is sufficient to "find a form of association which may defend and protect with the whole force of the community the person and property of every associate and by means of which each, coalescing with all, may nevertheless obey only himself, and remain as free as before."17 Rousseau's revised social contract allegedly achieves this self-conscious act of redemption. Traditional anarchism has always insisted on the plausibility of such a social arrangement without considering that it is the very socioeconomic and political practices of civilization along with 16 John Locke, The Second Treatise of Government, edited with an introduction by C.B. McPherson (Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Co, 1980) 23. 17 Jean Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract and Discourse on the Origin of Inequality, edited with an introduction by Lester G. Crocker (New York: Washington Square Press, 1976) 17-18. 8 the fake dialectics supporting them that make such an arrangement impossible. Utopia/Despair The lies that underpin civilization serve to erase the crimes that found it and to distort the primitive so that civilization's noblest promises seem to recreate and complete what was allegedly lost. Especially for the rich and powerful, civilization has its compensatory pleasures. But we miss the significance of the Fall if we look there. The search for meaning in the experience of material superabundance is not primordial; it is not even superficial. The veil of civilization's compensatory power lies not in varied material pleasures but in the equivalent impossibilities it engenders at the heart of our individual and social lives. The founding lies of civilization are the promises that what was lost in the Fall can be more than regained through mastery and control. Plato recognized this. It is why, out of his concern over the civilizational curse of the demand for luxuries, he invented a newer, more psychologically profound compensatory claim: contemplation of the form of the Good and the justice that it will ensure for the polis. The various, supposed redemptive promises are unattainable. They drive our alienation from Earth and from our human and especially non-human companions on this Earth into the underground of the psyche. Alienation, buried and suppressed, is substituted for by an allegedly attainable and sublime, transcendent truth. Devotion to a civilizing mission fills the void left by the Fall. In the hope for attainment of perfection through the mastery and control, the spiritual groundwork is laid for, at least, the acceptance of the terms of civilization, and, at most, a devotion of oneself to those terms. The alleged impossibility of turning back to live in freedom through identity with both human and nonhuman others engenders despair.18 A new (im)possibility must be created but one which is allegedly within reach, via contemplation, faith, or technical rationality. It must have all the characteristics of the primitive golden age which it claims to instantiate: social solidarity, spontaneous pleasure, identity between subject and object, and natural fitness for assigned tasks, to name a few. In these fundamental civilizational tropes, we discover two dishonest truth claims: the impossibility of returning to primitive life and the ostensible availability of a great (but actually, equally impossible) basis for reuniting ourselves with reality. Illusory hope in the face of hidden distress is the basic chemical ingredient of psychic shock. It creates in civilization a sort of double helix of despair, one strand being the submerged impossibility of returning to a golden age, and the more prominent strand, the impossibility of attaining the promised redemption. The essentially utopian character of western political theory is derived from this double helix. It can never take its bearings from the present except as the present is understood in reference to a future in which the civilizing promise has been obtained. The west is a non-place because it can never reach the imagined future nor return to the banished past. It is precisely because there has never been a single remedy for the inherent divisions, not to mention the founding crimes, of civilization that western political thought must endlessly churn out a variety of utopian schemes. Utopianism is the bad conscience of civilization. Those born to sweet delight, as Blake put it, go about their business 18 It is, perhaps, the poignant and persistent voicing of such despair that led the church to excise from the official version of the Bible Eden stories that have the first humans committing suicide over the magnitude of the loss of being ejected from paradise. Platt, Rutherford H., The Forgotten Books of Eden, (New York: Bell Publishing Company, 1980). 9 exploiting land and labor and occasionally ginning up public support for resource wars. They hold up the idea that a redemptive social scheme will soon arrive while their daily practice confirms that it never will.19 It is this fundamental indeterminacy which provides the psychic energy for civilization's harried pace. Civilization constantly needs more resources; but expansion is also the psychic (and psychotic) outlet for a nervous energy created from the double helix of utopian despair. There obtains in the dialectic of civilization something closely resembling Bateson's notion of the double-bind. Bateson locates the causes of schizophrenia in the social relations of the patient. Often the schizophrenic is caught in a dilemma with no possible resolution. Being stuck becomes a generalized system for interacting in the world. In the double bind a person is presented with contradictory compulsions each of which, if it is fulfilled, leads to punishment. A child is chastised for being dishonest but is also taught to win at all costs. A schizophrenic recovering from a psychotic episode sees his mother and embraces her. She reflexively stiffens, and her body language leads the patient to quickly remove his arms. Then she questions whether or not he loves her and admonishes him for not showing his true feelings. The double bind leads to a general and anxious sense of uncertainty and can lead a person to alternate between patterns of behavior expected of the schizophrenic--the schizophrenic participates in the very vicious circle of behavior that reproduces his pathology--or to outbursts of rage. In a sense the double bind presented in the dialectic of civilization is more intense. Both the options of a return to the primitive and its fulfillment in higher forms are attractive; they represent ideals of community solidarity, freedom, and personal sense of fulfillment that are genuinely human impulses. But one is not merely presented with punishment for seeking to actually attain either option; the options presented are impossibilities. We will be punished for trying to reach ends that are our own best, exclusive and unattainable options. Girard sees as a result of the double bind the transference of the unresolved tension to a scapegoat. The term itself comes form an ancient Jewish ceremony of atonement where a priest lays hands on a goat, transferring all of the sins within the community to it; the goat is then cast into the wilderness thus expiating the collective sins of the community. With the example of Jesus, "the lamb of God," the transference to the sacrificial victim is deepened inasmuch as the victim is seen as an innocent recipient of the community's collective transgressions. In modernity, where "violence is no longer subject to ritual and is the object of strict prohibitions, anger and resentment cannot or dare not, as a rule, satisfy their appetites on whatever object directly arouses them." The state, in Weber's all too telling description, has a monopoly on violence. In such a situation, new outlets for expiatory violence must be found. 19 In his Nuremberg Interviews, Nazi Gestapo founder, Chief of Staff of the Luftwaffe, and Reichsmarshall Herman Goering made some astute observations about war that help illuminate what we have in mind here. As he notes, people have no interest in going to war. Unaffected by propaganda, the most some "poor slob" can hope for is "to get back to his farm in one piece." It is up to the leaders to "drag them along." This is an easy matter: "All you have to do is tell them they are being attacked and denounce the pacifists for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same way in any country." In reality every "poor slob" knows that the best civilized life offers is to be left alone and in one piece. But civilizations need war; war requires the invention of a threat, a sub-human menace, the primitive, alien other. One hates that origin to which one cannot return. But there is also something to aspire to: "patriotism." It is the feeling, implanted from the first moments of education, that one is part of an organic, national whole. But the most basic conditions of civilization, especially division of labor, make social solidarity impossible. After all, it is the leaders who must drag the citizens along through fraud and the bosses and economic imperatives that drag them to work. 10 Victims substituted for the real target are the equivalent of sacrificial victims in distant times. In talking about this kind of phenomenon, we spontaneously utilize the expression "scapegoat." The real source of victim substitutions is the appetite for violence that awakens in people when anger seizes them and when the true object of their anger is untouchable. The range of objects capable of satisfying the appetite for violence enlarges proportionally to the intensity of the anger.20 Girard takes the boss as an example of the true object of violence. But the dialectic of civilization creates a psychologically untenable situation with two impossibilities held out as the alpha and omega of social existence. Harbored within these is an original act of violence. In creating "scapegoats," civilization always attributes to the sacrificial victim characteristics of the primitive. The enemy is subhuman, irrational, bare life, incapable of living in civilization, acting in contrast to all rules of civilization, savage, etc. There is then a reduplication of the original act of unrelenting violence. But the perpetrators are enacting violence upon themselves as well inasmuch as attributes of the primitive are held up--whether or not in the transcendent form--as essentially human: innocence, social solidarity, simplicity, truth-telling, communalism, and so on. Civilization is schizophrenic, divided within itself, hearing voices that can never quite be understood or realized, and, periodically, lashing out in paroxysms of violence .21 Conclusion: The Tragedy of the Unfortunate Fall The domestication of grains, legumes and other plants must be the greatest tragic irony in human experience. Domesticated grains serve a particularly important purpose in assuring a ready food supply. Their wild relatives have ears or pods that are more brittle and naturally tend to shatter and thereby scatter their seeds. By contrast, the domesticates are more pliable and remain encased within the pod; they "wait" for the human harvester who must remove the grain through threshing. Obviously, this variation (which depends on the mutation of just a single gene) allows for ready processing and easier storage. Moreover, among wild plants, germination and ripening varies slightly, thus increasing the likelihood of seed reproduction given varying times and amounts of rainfall. By contrast, among domesticates, germination and ripening of the plants happens virtually at the same time, again allowing the cultivator to know with relative precision when all the plants will be ready for harvesting. 22 The irony concerns the fact that it is precisely these qualities of domesticated plants that suit them to the "ideal state space," one in which those who labor to produce large volumes of fungible plant crops 20 René Girard, I See Satan Fall Like Lightning (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2001), see chapter twelve, "Scapegoat". 21 One might object that stories of the Fall have disappeared from popular culture. Technology, in its relentlessly forwardlooking and optimistic aspects has made history, in Ford's phrase, "bunk." A response might take two forms. First, consider that one of the foremost social theorists of technology, Marshall McLuhan, noted that electronic technology would create "a global village." Electronic media will recreate the immediate sense of communal experience found in the ancient village. In this case the dialectic of civilization would have simply been extended in an appropriate technological form. Alternatively, if we take seriously the idea that the Fall has, in fact, disappeared into the simulacrum, we might expect that violence will become completely unmoored from whatever cultural constraints once limited it. In this case we would expect to find the most random, senseless, and unpredictable acts of violence occurring on a more regular basis. 22 See Steven Mithen, After the Ice, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004). 11 can be located in close proximity to the various artisanal, military, religious and political specialists who comprise the state's core. In his remarkable book on "Zomia" George C. Scott notes that domesticated plants are perfectly suited to the tax collector and the general. As compared with wild plants or root crops, grain grows above ground and "predictably ripens roughly at the same time." The tax collector can survey the crop in the field as it ripens and can calculate in advance the probable yield.... if the army and/or the tax collector arrive on the scene when the crop is ripe, they can confiscate as much of the crop as they wish. Grain then...is both legible to the state and relatively appropriable.23 Scott further notes that grain is easily transported, has high nutritional and economic value per unit of weight, and is easily stored. Taken together these aspects of domesticated grain mean that, for state rulers, "large settled populations supported by abundant amounts of food were seen as the key to authority and power."24 Just as humans domesticate plants so do they themselves become domesticated within a political structure that will come to dominate them. The result is a tragic, unintended fall from primitive freedom, social solidarity and identity with the natural world. Domestication only happened incidentally and over a long period. Certainly, it was not a matter of choice. Its roots probably preceded the Younger Dryas. But once dramatic temperature increases occurred following this period, the possibilities for the success of plant selection and cultivation intensified dramatically. As Mithen puts it, the hunter gatherers who began to cary particular seeds around "must have noticed how much better their yields had become but they were surely quite unaware that those seeds were cultural dynamite."25 The dynamite was self-destructive. Across the globe, those cultures which most strongly embraced agriculture experienced rapid population growth and a need for territory. Hunter-gatherer cultures were displaced. Environmental degradation followed. It is in the Jericho Valley that agriculture on a large scale first occurs (7,500 BC at the latest) culminating in the appearance of sizable, relatively complex villages. By 6,500 BC the effects of intensive agriculture are unmistakeable. Valley hillsides "are quite barren--the soils exhausted by repeated cropping, and then washed away by winter rains after the remaining vegetation had been cleared for firewood." The depletion of soil nutrients and erosion forced farmers to go further afield for planting, for forage for their animals and for fuel. Streams ad rivers were silted by erosion and polluted by waste. Agricultural yields fell; infant mortality increased to catastrophic levels, and population collapsed. "Such is the story of all PPNB [Pre-pottery Neolithic B] towns of the Jordan Valley--complete economic collapse."26 Aside from the effects of collapse, other long term, sometimes incidental factors probably contributed to growing psychological distress. The increasing number of domesticated animals threatened carefully cultivated fields. They would have soon been seen as a pest to cultivators who would have "needed to impose a barrier between the domains of nature and human culture by fencing in their gardens. Such physical barriers may have also created a mental barrier between hunter-gatherers and horticulturalists, 23 24 25 26 12 James C. Scott, The Art of Not Being Governable, (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2009), p. 41. Ibid., pp. 41-42. Mithen, After the Ice, p. 54 Ibid., p 87 with people fencing themselves into one domain or the other."27 For Mithen the psycho-physical state to which neolithic farmers were ultimately brought is reflected in the cultural motifs found in one of the largest neolithic villages, Catalhoyuk in present day southern Turkey. A perimeter wall without gates or entrances (ladders were used for entrance and exit) surrounded the entire village. Clay figurines representing bulls' heads were prominent. During excavations stacks of them were found in certain residences, their faces covered in exotic designs. There is a figure of a woman seated on a throne, her hands resting on two leopards' heads; the leopard's tails wrap around the woman's body; she is seated next to a grain bin. Geometric designs are accompanied by depictions of great black vultures attacking headless people. Tiny people represented in a frenzy are surrounded by enormous deer and bulls. A sculpture of a woman's breasts with both nipples split apart and skulls of vultures, foxes and weasels staring out depicts "motherhood itself, violently defiled." To Mithen, "it seems as if every aspect of their lives had become ritualized, any independence of thought and behavior crushed out of them by an oppressive ideology manifest in the bulls, breasts, skulls, and vultures."28 Even in the earliest stages of domestication culture exhibits socio-pathological tendencies. If civilization, even in its earliest origins, is marked by extreme alienation and despair then diagnosing its elements is imperative. In the same way that Bateson discovered some of the basic patterns of social interaction that generated and reinforced schizophrenia, anarcho-primitivist writers like John Zerzan and Freddy Perlman have uncovered basic attributes of civilization that generate social pathologies and individual alienation. In Elements of Refusal Zerzan isolates such factors as abstract measurement of time and space, complex symbolism, number, specialization, and agriculture and shows how these have thrust humans out of simpler, more solidary, and more sane primitive life-ways into a world of relentless, alienating work and rule. In his "Against Leviathan" Perlman shows how state institutions have reinforced this process of extreme separation from self and from nature. It is possible that uncovering the elements of civilizational pathology will allow us to extricate ourselves from the double bind. In 1961, Bateson authored an introduction to a text called Perceval's Narrative. In Perceval's autobiography, Bateson discovered an early rendering of his own diagnosis of the double-bind. Perceval, who lived in the early 1800's, had experienced serious schizophrenic episodes throughout his life. But he began to grasp the social and relational dead ends in which he was caught and discovered ways to extricate himself from them. As Bateson wrote, Perceval had angrily “begun to realize the nature of the system that surrounded and controlled him” (1962b, p. xiii). And at the same time he painfully started to grasp and hold firmly a distinct, crucial piece of information in the changing flow of the delirium: the stabilizing role he had given himself, in syntony with the others, in the wider system.29 Anarcho-primitivism similarly denounces the detrimental forces of civilization, showing how we 27 Ibid., p. 346. 28 Ibid., p. 95. 29 Manghi, Sergio, "Traps for Sacrifice: Bateson's Schizophrenic and Girard's Scapegoat," World Futures: The Journal of General Evolution; Dec2006, Vol. 62 Issue 8, pp. 561-575. 13 ourselves reproduce the alienating effects of civilization when we identify with its claims. It insists that we break with those forces, rediscovering within ourselves, with others, and through primitive norms and values the means for re-establishing, as Zerzan calls it, a "future primitive." Perhaps there is a parallel between Perceval and indigenous forerunners of anarcho-primitivism. The latter similarly "self-diagnose" the social forces that hold them in a double bind and resist those forces by identifying and reversing them. In the account of his life given to Richard Erdoes, John Fire Lame Deer, takes the double bind into which Lakota traditionalists are thrust and turns it back against the allegedly superior, civilized mind. Civilization repeatedly tells Lame Deer that there is nothing to be gained and everything to lose in following traditional cultural beliefs. Anyway, say the experts, because so much has been lost traditionalists cannot perform the ceremonies properly. Lame Deer turns the tables with an impressive combination of humor, pathos, and philosophical acumen. In his first vision quest Lame Deer recounts how his grandmother had cut forty small pieces of flesh from her arm using a razor blade, the flesh to be dried and placed, along with certain, small, highly scared stones, within his rattle as a sacrifice by her for his ceremony. "Such an ancient ceremony with a razor blade instead of a flint knife," Lame Deer mockingly writes of the anthropologist's dismay. 30 But it is precisely because of the presence of his relatives, living and dead, human and non-human, that Lame Deer receives a vision that sets his life's proper course. On domestication Lame Deer writes, "That's where you fooled yourselves. You have not only altered, declawed and malformed your winged and four legged cousins; you have done it to yourselves. You have changed men into chairmen of the boards, into office workers, into time clock punchers."31 While "white men chase the dollar, Indians chase the vision." On each facet, Lame Deer mocks the idea of the superiority of civilization: Before our white brothers came to civilize us we had no jails. Therefore we had no criminals. You can’t have criminals without a jail. We had no locks or keys, and so we had no thieves....We had no money, and therefore a man’s worth couldn’t be measured by it. We had no written law, no attorneys or politicians, therefore we couldn’t cheat. We really were in a bad way before the white men came, and I don’t know how we managed to get along without these basic things which, we are told, are absolutely necessary to make a civilized society.32 In the end, it is only Indians who turn toward white ways who stand to lose everything. "Declawed and malformed," white people have lost the most basic aspects of self-knowledge. All creatures exist for a purpose. Even an ant knows what the purpose is--not with its brain, but somehow it knows. Only human beings have come to a point where they no longer know why they exist. They don’t use their brains and they have forgotten the secret knowledge of their bodies, their senses, or their dreams. They don’t use the knowledge the spirit has put into every one of them; they are not even aware of this, so they stumble along blindly on the road to nowhere--a paved highway which they, themselves, bulldoze and make smooth so that they can get faster to the big, empty hole which they'll find at the end waiting to swallow them up. It’s a quick comfortable super highway, but I know where it leads to. I have seen it. I’ve been there in 30 John Fire Lame Deer and Richard Erdoes, Lame Deer: Seeker of Visions, (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1972), p. 3. 31 Ibid., p. 189 32 Ibid., p. 117 14 my vision, and it makes me shudder to think about it.33 The nihilism in civilization derives from the hollow character of its highest aspirations. It seems that, by contrast, what is necessary in order to restore health is a dialectics of anti-civilization. Whether from anthropological sources, from anarcho-primitivists, from traditional indigenous persons, or from within oneself, simple good health requires new sources of valuation that are very old. The lies that conceal what has been done to primitive culture and what has been lost as a result must be exposed and lost knowledge resurrected. The alienation in technological civilization is reflected both in the desire to synthesize knowledge and spirituality and in the rampant signs of ill health, physically and psychologically, among masses of civilized people.34 Constantly we are told that it is only through an extension of civilized, technical means that the ills of civilization will be remedied. But in an apt illustration of the double-bind Heidegger poignantly wrote "Everything depends on our manipulating technology... We will...get technology 'spiritually in hand.' We will master it. The will to mastery becomes all the more urgent the more technology threatens to slip form human control."35 A Nazi partisan, Heidegger looked for a "free relationship to technology" in a special correspondence between ancient Greek and German languages, especially German Romantic poetry. A dialectics of anti-civilization, by contrast, goes "all the way down" as it were, seeking to uncover wisdom that civilization so blithely and viciously discards. Ironically, the goal of such a dialectics is to do away with its own method as dialectics is thought divided against itself, a refection of a culture riven by every sort of distance. Here too considering an indigenous logic of simultaneity and cultural motifs that ward off socially disruptive innovation would be instructive. 33 Ibid., pp. 190-191 34 Ray Kurzweil, The Age of Spiritual Machines, (New York: Penguin Books, 2000) 35 Heidegger, "The Question Concerning Technology," p. 5. Leading scientists' warnings of the impact of climate change are instructive. James Hansen, for example, speaks of the danger of "passing tipping points that lead to disastrous climate changes that spiral dynamically out of humanity's control." James Hansen "Global Warming Twenty Years Later," in The Global Warming Reader, ed. Bill McKibben, (New York: Penguin Books, 2012), p. 276. 15 Bibliography Adorno, Theodore W. Negative Dialectics. Translayed by E.B. Ashtom. New York: Continuum, 1973. Agamben, Georgio. Homo Sacer: Sovereing Power and Bare Life. Translated by Daniel HellerRoazen. Stanford, California: Stanford University, Press, 1998. Anderson, M Kat. Tending the Wild. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 2005. Baudriallrd, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation. Translated by Sheila Faria Glaser. An Arbor, Michigan: The University of Michigan Press, 1994. Diamond, Stanley. Primitive Views of the World. New York: Columbia University Press, 1960. Firth, Raymond. Primitive Ploynesian Economy. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1965. Girard, Rene. I See Satan Fall Like Lightning. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2001. Hansen, James. "Global Warming Twenty Years Later," in The Global Warming Reader. Edited by Bill McKibben, (New York: Penguin Books, 2012), p. 276. Heidegger, Martin. The Question Concerning Technology and other Essays. Translated and with an introduction by William Lovitt, (New York: Harper Row Publishers, 1977. Kroeber, Theodora. Ishi In Two Worlds. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1961. Kurzweil, Ray. The Age of Spiritual Machines. New York: Penguin Books, 2000. 16 Lame Deer, John Fire and Richard Erdoes, Lame Deer: Seeker of Visions. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1972. Locke, John. The Second Treatise of Government. Edited with an introduction by C.B. McPherson. Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Co, 1980. Lotringer, Sylvere in George Bataille, On Nietzsche. Translated by Bruce Boone. St Paul, Minnesota: Paragon House, 1994. Lovejoy Arthur O. Essays in the History of Ideas. New York: Capricorn Books, 1960. Manghi, Sergio. "Traps for Sacrifice: Bateson's Schizophrenic and Girard's Scapegoat," World Futures: The Journal of General Evolution; Dec2006, Vol. 62 Issue 8, pp. 561-575. Mithen, Steven. After the Ice, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004. Packenham, Thomas. Racism: A. DVD. Directed by Paul Tickell. London: BBC, 2007. Perlman, Fredy. Against His-story, Against Leviathan. Detroit, Michigan: Black and Red Books, 1983. Plato. The Republic. Translated by Benjamin Jowett. New York: Anchor Books, 1973. Platt, Rutherford H. The Forgotten Books of Eden.New York: Bell Publishing Company, 1980. Rousseau, Jeanne Jacques. The Social Contract and Discourse on the Origin of Inequality. Edited with an introduction by Lester G. Crocker. New York: Washington Square Press, 1976 Scott, James C. The Art of Not Being Governable. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2009. Zerzan, John. Elements of Refusal. Seattle, Washington: Left Bank Books, 1988. 17