Sites of Resistance: Weblogs and Creative Commons Licenses

Clancy Ratliff

University of Minnesota

ratli008@umn.edu

Abstract:

In this essay, I analyze the growing trend of Creative Commons-licensed weblog content.

Data from a survey I distributed reveals that bloggers are obtaining CC licenses instead of

“All Rights Reserved” because they want to help create an intellectual commons. I argue that

what makes the weblog a public-domain-oriented genre is its collaborative model of

composition and reliance on others' content. More important, though, is weblogs' cultural

context, which includes major shifts in the intellectual property landscape: the rise of open

source and publicly licensed software, the tightening of copyright restrictions, and the

popularity of and controversy surrounding peer-to-peer networks.

In recent months, weblogs have garnered significant interest among Internet

users, the popular media, and academics in a variety of areas, including psychology,

sociology, rhetoric and composition, journalism, cultural studies, and Internet research.

Blogging is quickly becoming a leading form of communication on the Internet, and the

implications of this new genre for communication and culture are becoming clearer every day.

Because relatively few weblogs are password-protected, blogging is very much a public

activity, and the content, though implicitly copyrighted (as is all Web content), is quoted,

linked to, responded to, and built upon freely. The weblog, by design, is a collaborative genre

of writing that challenges traditional notions of authorship and intellectual property. Creators

of weblogs, called bloggers,are taking increasing advantage of this fact and are seeking out

and implementing alternatives to the current model of heavy copyright protection of ideas.

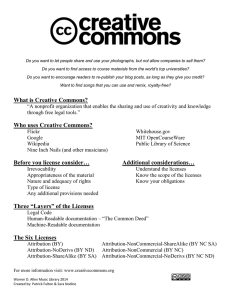

One of these alternatives is getting a Creative Commons license for content.

Thousands of bloggers are now getting Creative Commons licenses for the content on their

weblogs, which includes creative writing, essays, photographs, visual art, and even audio and

1

video. Creative Commons was designed in 2001 by lawyers to help citizens who compose

creative and intellectual content and are affected by recent U.S. copyright laws and

controversies contribute to the intellectual commons by giving up some, or all, of the

copyright privileges granted to them by law. In the essay that follows, I will review the history

of weblogs, give a brief review of copyright law as it has developed in United States history,

trace the development of Creative Commons and its mission, and examine the trend of

Creative Commons licenses on weblogs using data from brief email interviews with ten

bloggers who have Creative Commons licenses on their weblogs. I will then point out the

implications of Creative Commons-licensed weblog content for an intellectual commons.

Is the use of Creative Commons licenses in blogging practices contributing to the

realization of the Web as an intellectual commons? I will argue that it is, due to the

compelling cultural context in which bloggers are writing: blogging began and evolved pari

passu with other important technological and cultural events: the United States v. Microsoft

case and the rise of GPL (General Public License) and open source software, the tightening

of copyright restrictions that came with the 1998 Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act

and the Digital Millenium Copyright Act, and the popularity of peer-to-peer networks along

with the music industry’s attempts to eliminate them.

A Brief Review of Weblogs

In 1997, Jorn Barger started using the term weblog to refer to his online journal, Robot

Wisdom1 and other maintainers of sites similar to his followed suit. Weblogs, also called

blogs, are frequently updated personal journal-style Web sites on which people post links to

and commentary on articles, other Web sites, and other weblogs.

2

They can be devoted to

only one topic, or they can reflect what the blogger is interested in at any given time. They

can have one composer, or they can be community weblogs with thousands of contributors.

All posts to the weblog are time-stamped with the most recent post at the top, making their

structure not that of a coherent, logical argument, but a reverse chronological structure

governed by spontaneity and novelty. Maintainers of weblogs write about their jobs, ideas,

political views, research interests, childhood memories, and dreams. They post reviews of

movies they’ve seen, books they’ve read, and albums they’ve heard. They read other

weblogs and freely copy and paste others' content onto their own weblogs, usually with a link

back to the original post, often responding and building upon the original post. Often, a

blogger will write an essay, post it to his or her weblog, and solicit feedback. Other bloggers

post comments underneath the essay (or link to the essay and write response pieces on their

own weblogs), and the blogger who wrote the essay may revise it, or simply let the comment

discussion stand on its own as a conclusion to the essay. This is the collaborative authorship

model blogging offers. Because of the novelty of weblogs, scholarly literature about blogging

is not plentiful. Most of the extant publications about weblogs are how-to manuals for starting

and maintaining a weblog using one of the many software tools, but they also offer insight

into the uniqueness of the weblog as a genre that challenges traditional notions of authorship

and intellectual property. I would like to review briefly three of these publications.

Bausch, Haughey, and Hourihan (2002) center on how to create and maintain a

blog using Blogger as a software application, but they provide a thorough contextualization of

blogs as well, including a historical account, explanation of different kinds of weblogs,

including multi-author or community weblogs, single-author weblogs, business weblogs, and

Intranet weblogs. Rodzvilla’s (2002) anthology is a collection of weblog posts that originally

3

appeared on the Internet. The authors of the posts focus on how their weblogs are affecting

them, why they blog, and why they read weblogs. Mortensen and Walker’s (2002) article

analyzes how blogging influences the way the authors think and points to the weblog’s

potential as a research tool. Mortensen and Walker also use Habermas’s theory of the public

sphere as a framework to examine weblogs as liminal spaces between public and private,

and they offer insight into the “social network of blogging” (p. 271)

The first weblogs were launched between 1994 and 1998. Justin Hall’s weblog,

“Links from the Underground,” dates back to 1994 (Bausch, Haughey, & Hourihan, 2002, p.

9). Bausch, Haughey, and Hourihan’s book and Rebecca Blood’s essay in We’ve Got Blog

describe the explosion of the weblog when, in July 1999, several no-cost, easy-to-use weblog

content management tools were released: Pitas, Blogger, and Groksoup. Before the tools

were released, most bloggers were Web designers, software designers, and computer

scientists, and keeping a weblog required knowledge of hypertext markup language (HTML)

and Java® tools. The new software tools for weblogs made posting to a weblog no more

difficult than sending an e-mail, which enabled many people at all different computer skill

levels to create and maintain a blog. Evan Williams, the co-creator of Blogger, addresses the

growth in popularity of weblogs in a February 28, 2001 interview with Giles Turnbull in We’ve

Got Blog:

For the first couple months [after the release of Blogger], we got 1020 new users a day. We launched a new version in November of

’99, after which we got a relatively large influx and were up to about

2,300 by the end of the year. Through last year, we averaged 20 to

40 percent growth per month, and that continues today. As of right

4

now, there are 117,970 registered users. 19,582 of those signed up

in January [2001] (p. 80).

The number of blogs is now in the millions (Blogger alone has over one million members),

and popular weblogs get hundreds of thousands of hits per day.

All of the pieces attempt to account for this phenomenal popularity by discussing

the myriad reasons why people blog and read weblogs. Mortensen and Walker say that their

weblogs “became tools with which to think about [their] research, its values, connections and

links to other aspects of the world. They altered the way in which we approached online

communication, and have influenced the writing of both dissertations” (251) Brad L. Graham,

in the Rodzvilla anthology, keeps a weblog out of a “need to publish,” a way to pass along

jokes to friends without sending them multiple e-mail messages, a “license to explore” the

Web and a means of learning more about Web design, and means of participation in the

weblog community (p. 37-39). Bausch, Haughey, and Hourihan, accounting for why people

read weblogs, point to the voyeuristic allure of getting a glimpse into other people’s minds

and the function of a weblog as a filter of Web sites. Instead of finding a site through a search

engine that simply matches search terms with words in the text of a site, one can go to the

weblog of a person whose opinion he or she values and find sites that the blogger, an

intelligent human being with ethos, has personally reviewed and found worthy of linking.

Bloggers often have spaces for reader comments underneath each post, inviting audience

response. The motivations behind keeping a weblog are telling; in none of the sources I

reviewed did anyone say that they kept weblogs for financial gain, or that monetary incentive

play any role at all in whether they kept weblogs or not.

Audience response to weblogs, and the sense of community blogs foster, is also

5

a common theme in the conversation about weblogs. Bausch, Haughey, and Hourihan

recommend adding a comment function to Blogger so that the author of the weblog can

communicate with his or her readers. They also recommend creating an “About” page on

which the blogger puts personal information about himself or herself and looking regularly at

the Web referral statistics, in other words, who is linking to the weblog, who is visiting the

weblog, and from where the reader surfed to find the blog. Mortensen and Walker note that

“[w]eblogs tend to come together in clusters as they link to each other” (271). The popularity

of a weblog is measured in how many sites link to it, which all three sources affirm.

Conversations can also take place across different weblog sites by way of linking. This

proliferation of linking is one way that the use of Creative Commons licensing has become

popular among weblogs; when one blogger sees a Creative Commons license on someone

else's weblog and clicks through to Creative Commons Web site, he or she might also get a

Creative Commons license. In the next section, I will review briefly the history of copyright in

the United States and explain how recent developments spurred the development of Creative

Commons.

A Brief History of Copyright

The reason the United States drafted copyright law was originally to encourage creativity and

innovation. Copyright law began with the public’s interests in mind: first, it was conceived as a

quid pro quo, meaning that the public gave the exclusive right of distribution and creative

control to the creator for a limited time, with the understanding that the work would enter the

public domain at the end of the time allotted. Then it became a sort of bargain, in which the

public “bribed” creators to produce more work by granting exclusive copyright (Litman, 2001,

6

p. 78). The original Copyright Act of 1790 gave the creator these rights for fourteen years,

with an option to renew for an additional fourteen years. In 1831, Congress made it possible

to renew the copyright for another fourteen years. Congress extended the copyright term

again in 1909, 1976, and then again in 1998 (Vaidhyanathan, 2001, p. 45). Under the current

copyright law, as soon as any creative expression enters a fixed medium—for example, as

soon as any file is saved on any hard drive, or as soon as an exposure is made onto a piece

of film, or any words are written with pencil on paper—it is automatically copyrighted for the

life of the author plus seventy years. The process by which copyright laws are made is

skewed in favor of the private industries and their copyright lawyers; in other words, the

content industries—record companies, motion picture companies, television networks, cable

television companies, satellite television companies, and publishers—are deciding what kinds

of laws they want, and their lobbyists are presenting them to Congressional representatives,

who, in turn, pass them without much consideration of their implications for the public

interest, which they are supposed to represent (Litman, 2001). Some argue that these

extensions of copyright terms are moving toward making copyright perpetual and leaving the

public not only without representatives of their interest in the intellectual property debate, but

without ideas to use for new innovations and creations. Some are "copyright-rich" and some

are "copyright-poor," (Vaidhyanathan, 2001), and, seeing this gap between the two,

concerned citizens decided to fight the laws that they thought of not as encouragement of

creativity and innovation, but the stifling of it, the corporate ownership of culture.

Creative Commons: Its History and Mission

Creative Commons began in 2001 as a collaborative effort between Harvard Law

7

School and Stanford Law School. Lawrence Lessig, a well-known writer and lawyer who is

also an activist for shortening copyright terms, is a founding member of Creative Commons.

Their goal is “to develop a rich repository of high-quality works in a variety of media, and to

promote an ethos of sharing, public education, and creative interactivity” (About us, 2003). In

December 2002, inspired by the General Public Licenses for software, they released their

Creative Commons licenses. The terms include Public Domain Dedication, Attribution,

Noncommercial Use, No Derivative Works, and Share Alike. Another of Creative Commons’

projects is the “Founder’s Copyright.” If an author licenses a book or an artist licenses a piece

of art under a Founder’s Copyright, the creator will hold the copyright for fourteen years with

an option to renew for an additional fourteen. In support of the Founder’s Copyright, some

bloggers have a button on their weblogs that says, “Create like it’s 1790!” For weblogs, the

most popular combination of selection items in the range of licenses offered is Attribution,

Noncommercial Use, and Share Alike. That is, people may use that particular blogger’s work

as long as they attribute it to the author of the weblog, do not use it for commercial gain, and,

if they create derivative works based on the weblog, license them in a similar “Some Rights

Reserved” way. This combination, although popular among bloggers, is not the only

combination of licensing terms that bloggers use. Lessig, for example, has Attribution as the

only term in the license on his weblog. The license on Doc Searls’ weblog is a Public Domain

Dedication, meaning that he has relinquished all copyright privileges.

Bloggers with Creative Commons Licenses

To move toward answering my original question of whether or not the use of Creative

Commons licenses in blogging practices contributing to the realization of the Web as an

8

intellectual commons, I emailed ten bloggers with CC licenses and asked them the following

questions3:

●

How did you find out about Creative Commons?

●

Why did you get a Creative Commons license for your weblog?

●

What do you think the value of a Creative Commons-licensed blog site is over a traditional

"All Rights Reserved" site?

Their responses have informed the reasons I point out why bloggers are contributing to

the Web as an intellectual commons. I realize that such a small sample of bloggers cannot

justify a generalization to the entire population of bloggers with Creative Commons licenses,

but I maintain that their responses to my questions are an accurate qualitative representation

of bloggers' thoughts on Creative Commons.

The implementation of Creative Commons licenses has become akin to a meme

in blogging communities. Because blogging is a community activity the Creative Commons

license phenomenon has spread quickly. The communal nature of the activity of blogging

plays a role in weblogs’ contribution to the Web as an intellectual commons. Widely-read

weblogs, such as Slashdot, Doc Searls' weblog, Lessig's weblog, and Kuro5hin, have been

powerhouses in the spread of Creative Commons licenses. All the people who responded to

my questions said that they had found out about Creative Commons via other weblogs. Matt

Haughey, co-author of We Blog: Publishing Online with Weblogs, and one of the creators of

popular community weblogs Metafilter and Blogroots, is also the creative director of Creative

Commons. Other widely-read bloggers also have Creative Commons licenses.

The vast majority of bloggers do not get paid for keeping their weblogs at all; they

do it in order to freely give and publish their ideas and receive other ideas in return. The

9

bloggers I interviewed, when asked why they got Creative Commons licenses, all expressed

desires to share ideas and relinquish some control over their content. Timothy Jarrett writes,

"I've been arguing the cause of the intellectual commons long enough that I felt I should take

action once an alternative was available." The idea that composers need a financial incentive

in order to create and distribute content is not the reality of blogging communities. Bloggers

keep their weblogs for pleasure, to write and be read by others, and to engage in a

collaborative meaning-making process. Charles Lowe writes, “I am convinced that our society

would be better off with copyleft as the default mode of publishing/software publication and

creation. After all, copyleft and open source are a more collaborative model for knowledge

creation that the current intellectual property paradigm.” Jarrett writes, “The philosophy of

subverting the continued elimination of the intellectual commons through explicitly declaring a

share-alike license struck me as brilliant.” Other bloggers I corresponded with echoed similar

sentiments of preferring a shared-knowledge, anti-ownership model of producing content.

They prefer the freedom Lessig refers to in The Future of Ideas:

Because our bias is to ignore the choice between the free and the

controlled, we ignore the costs of a system of control over a system

that remains free. We fail to see the benefits from freedom because

we assume that freedom is not possible. We assume that creativity

and innovation and growth will occur only where property and

markets function most strongly.

10

Against this ideology, I offer the Internet. Against this

bias, I submit a tradition that has understood balance better. The

past decade has demonstrated the value of the free; that freedom

came from the Net’s architecture (p. 238).

How can we account for many bloggers' strong conviction that an intellectual commons is of

paramount importance? To answer that question, I argue that we should look at bloggers and

blogging in their context. One might argue that Creative Commons licenses are just a fad in

blogging, but my claim is that most bloggers with Creative Commons licenses are informed

citizens who understand, at least to some extent, copyright law and intellectual property and,

as concerned citizens, use their Creative Commons licenses as statements responding to the

discourse from corporations and the government.

Weblogs in Context

Weblogs emerged in the early 1990s, but they did not become mainstream until

1999. The cultural context with regard to copyright and piracy is particularly important to

establish here, because the late 1990s and early 2000s saw dramatic shifts in the U.S.

intellectual property landscape that have greatly influenced the way members of the public,

especially those with access to and knowledge of digital technology, view the copyright

system. Bloggers linked to and responded to the proliferation of news stories about copyright,

piracy, and the public domain.

The first phenomenon is Microsoft’s attempt to create a monopoly with its

Windows interface and MS-DOS (Microsoft Disk Operating System), while at the same time

refusing to share the source code from any versions of its products. Lessig (2001) states that

11

“[w]hile Microsoft had built an important platform upon which

developers across the world had constructed code, Microsoft had

adopted a practice that chilled certain kinds of innovation. When an

innovator had a technology that threatened Microsoft’s platform,

Microsoft, the government claimed, adopted a strategy to kill that

innovation. The platform, in other words, turned against some kinds

of innovation, while no doubt protecting others.” (p. 62)

In response to this threat of monopoly, open source software and operating systems and

software and operating systems licensed under a General Public License (GPL) have

become a public-commons alternative to Microsoft and Apple products. A GPL states that if

auser adds to or modifies the code of a software tool or operating system, he or she must

release that new version under a GPL as well. In other words, GPL-licensed software cannot

be bought or sold. Open-source software can, but the source code must still be made public.

These new policies, made in the mid-1990s, were being formulated at the same time as the

earliest weblogs were being published.

The second significant cultural factor to consider with the emergence of blogging

is the 1998 passing of the Digital Millenium Copyright Act. Lessig (2001) argues that the

“particularly troubling” aspect of the law was its anticircumvention provision, which “regulates

code that cracks code that is intended to protect copyrighted material” (p. 187). Companies

that produce DVDs and CDs began putting CSS (Content Scramble System) technology on

their products so that only machines licensed to play CSS-encrypted discs—machines with

Macintosh OS and Windows MS-DOS—could play the discs (Lessig, 2001, p. 188-189). I

would argue that this move on the part of the content industries, which was considered

12

totalitarian by many, served as a direct challenge to the anarchist ethos of computer

aficionados. When a program called DeCSS was released to enable CSS-encrypted discs to

play on computers using Linux OS and other operating systems, “the industry went nuts”

(Lessig, 2001, p. 189).

The third phenomenon to emerge along with blogging is the popularity of file

sharing applications and peer-to-peer networks such as KaZaa, Gnutella, and the nowdefunct Napster and the recording industry’s subsequent attempts to quash file sharing and

users’ making digital copies of compact discs. The posturings of persons such as Hilary

Rosen of the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) and Jack Valenti of the

Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) have facilitated perhaps the biggest backlash

of all against the current copyright system. Users who enjoy music want to be able to

download songs to their hard drives for free, and cite the high price of CDs and DVDs as the

reason they would rather download them than buy them. A recent AOL members-only poll

indicated that 85% of members who responded to the poll do not feel that downloading

music, images, and movie clips is wrong. The popularity and subsequent criminalization of

peer-to-peer file sharing have coincided with the rise of blogging. Bloggers are the same

people who read about and/or use open source software and upload and download files from

peer-to-peer networks.

13

Conclusion: Blogging and the Commons

In keeping with the freedom of the Net’s architecture that Lessig pointed out, I would like to

gesture toward one promising way that bloggers are helping to make the Internet an

intellectual commons. Creative Commons license options are built right into the content

management software tools of two applications: the popular Movable Type and

Userland/Manila. I argue that this integration of “thin copyright” and “some rights reserved” at

the software level has important implications for the claim that weblogs, more so than other

Web sites, are helping to make the Internet an intellectual commons. Andrew Ó Baoill adds

that "As XML reading tools improve it [Creative Commons licensing] may allow better

syndication - automated harvesters can check whether reprinting is allowed (and under what

conditions) and use this to create aggregator-style sites."

These tools, also known as RSS (RDF—Resource Description Framework—Site

Summary) feeds, are news aggregators that can read the machine-readable CC licenses,

making the terms of the CC license accessible through the feed. Search engines can also

read the CC licenses. Eventually, users will be able to filter out anything that does not have a

CC license, which means that if someone wants to search for potential material to use in

teaching, public domain clip art to use in graphic design, etc., he or she can filter out any “all

rights reserved” material, and the intellectual commons will be more easily accessible to all.

It was perhaps a happy accident that blogging emerged along with explosive

debates in intellectual property and copyright law. I have argued that the same generation of

Web users and composers has participated in blogging as well as witnessed the ridiculous

ownership claims made by the content industries. They have seen the dwindling of the public

domain, but they are also helping to restore it through their creative content. They are

14

resisting near-perpetual copyright, corporate ownership of culture, Digital Rights

Management, software monopoly, and inhibition of fair use via their blog sites. Litman (2001)

argues that people need to be able to understand a law and see that it makes sense before

they are willing to follow it. Creative Commons responds to this by making their license terms

broad and flexible for new technology: a copyright system for the future. Kara Kerwin said

that “[t]here needs to be a critical mass of people, publishing companies, news agencies,

corporations, etc. who understand, use, and adhere to the CC license, (and there might never

be) before the CC has value.” Haughey has a more optimistic view, saying that

Weblogs have turned thousands of former web readers into web

writers, and they're creating hundreds of thousands of pages of web

content. Many are choosing to license their work and I think they're

setting a great example to other communities. Giving away a bit of

control in the spirit of sharing is a mainstay among weblogs, and I

hope independent music communities and beginning film makers take

notice and follow suit (personal communication, April 29, 2003).

Maybe Creative Commons will not overturn the content industries’ ownership claims, but the

use of their licenses and the flagrant dismissal of copyright laws by the general public will

surely send the content industries and the government a message they need to hear.

15

Notes

1. Available at http://www.robotwisdom.com.

2. Archives for TechRhet are available at http://www.interversity.org.

3. Those who replied to my email gave me their permission to publish their words and

attribute their words to them, without stripping the quotations of identifiers.

4. Ironically, Mena Trott and Benjamin Trott, the founders of Six Apart, the company that

makes Movable Type, do not have Creative Commons licenses on their weblogs

(http://www.dollarshort.org and http://www.stupidfool.org respectively). Six Apart’s site

(http://www.sixapart.com/) also does not have a CC license. I plan to inquire about this

soon.

16

References

About us. (2003). Retrieved April 26, 2003, from

http://new.creativecommons.org/learn/aboutus/

Bausch, P., Haughey, M., & Hourihan, M. (2002). We blog: Publishing online with

weblogs. Indianapolis, IN: Wiley Publishing.

Ebyryan. (2003). Re: Creative Commons Licenses on weblogs. Kairosnews: a weblog for

discussing rhetoric, technology, and pedagogy. Retrieved April 26, 2003, from

http://www.kairosnews.org/modules.php?op=modload&name=News&file=article

&sid=1824&mode=flat&order=0&thold=0.

Haughey, M. (2003). Notable recent CC licensors. Creative Commons weblog. Retrieved

April 26, 2003, from http://creativecommons.org/weblog/entry/3615.

Haughey, M. (2003). Harvard Blogs and Creative Commons. Creative Commons weblog.

Retrieved April 26, 2003, from http://creativecommons.org/weblog/entry/3648.

Lessig, L. (2003). Weblogs and the public domain. Lessig blog. Retrieved April 26,

2003, from http://cyberlaw.stanford.edu/lessig/blog/archives/2003_04.shtml#001066.

Lessig, L. (2003). Great CC news. Lessig blog. Retrieved April 26, 2003, from

http://cyberlaw.stanford.edu/lessig/blog/archives/2003_04.shtml#001065.

Lessig, Lawrence. (2003). Ticketstubs. Lessig blog. Retrieved April 26, 2003, from

http://cyberlaw.stanford.edu/lessig/blog/archives/2003_01.shtml#000823.

Lessig, L. (2003). Ways say ‘some rights reserved.’ Lessig blog. Retrieved April 26,

2003, from http://cyberlaw.stanford.edu/lessig/blog/archives/2003_03.shtml#001032.

Lessig, L. (2002). The future of ideas: the fate of the commons in a connected world.

New York: Vintage.

17

Litman, J. (2001). Digital copyright. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

Lowe, C. (2003). Re: Creative Commons Licenses on weblogs. Kairosnews: a weblog for

discussing rhetoric, technology, and pedagogy. Retrieved April 26, 2003, from

http://www.kairosnews.org/modules.php?op=modload&name=News&file=article

&sid=1824&mode=flat&order=0&thold=0.

Moore, A.D. (2001). Intellectual property & information control: philosophic foundations and

contemporary issues. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Mortensen, T., and Walker, J. (2002) Blogging thoughts: personal publication as an online

research tool. Retrieved April 26, 2003, from

http://www.intermedia.uio.no/konferanser/skikt02/docs/ Researching_ICTs_in_context-Ch11-Mortensen-Walker.pdf

mt26 – Guide to the new features in Movable Type 2.6. (2003). Retrieved April 26, 2003,

from http://www.movabletype.org/docs/mt26.html#creative%20commons%20licenses.

Munger, D. (2003). Re: Creative Commons Licenses on weblogs. Kairosnews: a weblog

for discussing rhetoric, technology, and pedagogy. Retrieved April 26, 2003,

from http://www.kairosnews.org/modules.php?op=modload&name=News&file=article

&sid=1824&mode=flat&order=0&thold=0.

Rodzilla, J. (Ed.). (2002). We’ve got blog: How weblogs are changing our culture.

Cambridge, MA: Perseus Publishing

Searls, D. (2003). The whatever license. The Doc Searls Weblog. Retrieved April 28, 2003,

from http://doc.weblogs.com/2003/04/13#theWhateverLicense

Winer, D. (2003). Creative Commons, RSS and Manila. Retrieved April 26, 2003, from

http://manila.userland.com/creativeCommonsRssManila

18