Emergency Department and Urgent Care for Children

Excluded From Child Care

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT: Previous studies have

revealed that children in child care are frequently ill with mild

illness and are unnecessarily excluded from child care at high

rates.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS: Parent race/ethnicity, single parents,

and work-related concerns are associated with increased

emergent/urgent care use for a sick child excluded from child

care, even for mild illnesses.

AUTHORS: Andrew N. Hashikawa, MD, MS,a David C.

Brousseau, MD, MS,b Dianne C. Singer, MPH,c Achamyeleh

Gebremariam, MS,c and Matthew M. Davis, MD, MAPPc,d

aDepartment of Emergency Medicine, cChild Health Evaluation

and Research Unit, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann

Arbor, Michigan; bSection of Pediatric Emergency Medicine,

Department of Pediatrics, Medical College of Wisconsin,

Milwaukee, Wisconsin; and dInstitute of Healthcare Policy and

Innovation and Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy, University

of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan

KEY WORDS

child care, illness, urgent care, emergency care, policy, survey,

and parents

abstract

BACKGROUND: Children in child care are frequently unnecessarily excluded for illness. We investigated parental use of urgent medical

evaluation for sick children unable to attend child care.

METHODS: In May 2012, authors conducted a nationally representative

survey of parents, who completed online questions regarding child illness causing absence from child care and their medical care-seeking

behavior. Main outcome was parents’ use of emergency department or

urgent care (ED/UC).

RESULTS: Overall survey participation rate was 62%. Of participating

parent cohort with children 0 to 5 years old, 57% (n = 357) required

child care, of which 84% (n = 303) required out-of-home child care.

Over 88% of parents sought acute medical care for their sick children unable to attend child care. Approximately one-third of parents needed a doctor’s note for employers and/or child care. Parents

sought medical evaluation (.1 option possible) from primary care

(81%), UC (26%), or ED (25%). ED/UC use was most common for rash

(21%) and fever (15%). Logistic regression indicated ED/UC use was

significantly higher among single/divorced parents (odds ratio [OR] =

4.3; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.5–13.5); African American parents

(OR = 4.2; 95% CI: 1.2–14.6); parents needing a doctor’s note (OR = 4.2;

95% CI: 1.5–11.7); and those with job concerns (OR = 3.4; 95% CI: 1.2–9.7).

CONCLUSIONS: A substantial proportion of parents whose sick children cannot attend child care seek care in ED/UC. Training child

care professionals regarding appropriate illness exclusions may

decrease ED/UC visits by lowering child care exclusions. Pediatrics

2014;134:e120–e127

ABBREVIATIONS

AAP—American Academy of Pediatrics

ACA—Affordable Care Act

aOR—adjusted odds ratio

CI—confidence interval

ED—emergency department

GfK—GfK Custom Research, LLC

NPCH—National Poll on Children’s Health

OR—odds ratio

UC—urgent care

Dr Hashikawa conceptualized and designed the study, helped

with data acquisition, and drafted the initial manuscript;

Dr Brousseau helped conceptualize and design the study,

contributed substantially to data interpretation, and critically

reviewed and revised the manuscript; Ms Singer made

substantial contributions to study design, study analysis and

data interpretation, and critically reviewed the manuscript;

Mr Gebremariam carried out data analysis and interpretation

and critically reviewed the manuscript; Dr Davis made

substantial contributions to study design and development of

data collection instruments and critically reviewed and revised

the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript

as submitted.

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2013-3226

doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3226

Accepted for publication Mar 25, 2014

Address correspondence to Andrew N. Hashikawa, MD, MS,

Department of Emergency Medicine, Children’s Emergency

Services, 2800 Plymouth Rd, Suite G080, NCRC Building 10, Ann

Arbor, MI 48109-2800. E-mail: drewhash@umich.edu

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275).

Copyright © 2014 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have

no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: No external funding.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated

they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

e120

HASHIKAWA et al

Downloaded from by guest on October 1, 2016

ARTICLE

More than 80% of the children in the

United States will require nonparental

child care by 6 years of age because of

working parents, welfare reform, and

economic necessity.1–3 Children in child

care center settings have more upper

respiratory infections, diarrheal illness,

ear infections, and myringotomy tube

placement than children who stay at

home exclusively.4–7

Previous research demonstrates that

ill children are routinely excluded from

child care unnecessarily given that

most child care-related illnesses are

minor in severity.8–11 Unnecessary

exclusions place a substantial burden

on working families, businesses, and

health care resources.1,9,12–18 Nationally, an estimated 44 million workers

lack any paid sick leave benefits to

care for sick children, disproportionately affecting poor and minority

families.19

The American Academy of Pediatrics

(AAP), in its publication Caring for Our

Children: National Health and Safety

Performance Standards for Out-ofHome Child Care and Early Education

Programs,20 outlined clear child care

illness exclusion guidelines, particularly

if the child cannot participate comfortably in activities or needs more attention

that staff can provide safely. Several

studies demonstrate that child care

provider adherence to the guidelines is

low, however, and training is unavailable

in most states.8,9,21,22

Consequently, child care providers unaware of AAP national child care recommendations may increase parents’

perceived need for urgent medical

evaluations for nonurgent conditions

to avoid loss of wages or missed time

from work.23–26 An estimated 50% to

80% of the 25 million pediatric visits to

the emergency department are for

nonurgent conditions.27–30 High emergency department (ED) utilization for

nonurgent conditions leads to increased

cost, prolonged wait times, patient dis-

satisfaction, and adverse events.28,31

Studies suggest that most families

seeking nonurgent pediatric ED visits

report having a regular primary care

physician.27,32 Multiple factors associated with pediatric nonurgent ED

utilization have been identified, including single parent status, Medicaid

insurance, lack of convenient/weekend

hours, parent ED utilization, and quality

of relationship with primary care provider.27,28,33,33 Many of these factors are

prominent characteristics of parents

who need child care services. No

studies of pediatric ED or acute care

use, however, have assessed the impact that child care illness might have

on parents’ need for urgent medical

evaluations.

The C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital National Poll on Children’s Health (NPCH)

survey was used to investigate the prevalence and characteristics of parents

who use the ED or urgent care (UC) for

sick children unable to attend child

care.

METHODS

Study Design and Sample

The NPCH, located within the Child

Health Evaluation and Research Unit of

the Division of General Pediatrics at the

University of Michigan, measures perceptions concerning major health care

issues and trends for US children. The

NPCH is conducted in partnership with

the GfK Custom Research, LLC (GfK)

Group’s Web-enabled KnowledgePanel,

a probability-based panel designed to

be representative of the US population.

The KnowledgePanel has served as the

sampling frame for several other peerreviewed studies on health topics related to children.34–37

The NPCH sample includes oversampling

of parents and members of racial and

ethnic minorities to ensure adequate

representation of those groups. Panel

participants were originally chosen

through random selection of telephone

PEDIATRICS Volume 134, Number 1, July 2014

numbers and residential addresses and

were invited by GfK to participate by

telephone or mail. If individuals agree to

participate but do not already have Internet access, GfK provides them a laptop and Internet service connection at no

cost. Panelists receive unique log-in

information for accessing surveys online,

and then are sent emails each month

inviting them to participate in research

ona wide array of topics.After joining the

panel, participants provide individual

and household demographic data, used

for sampling purposes.

The survey for the current study was

piloted in April 2012 by using a separate

convenience sample of 105 KnowledgePanel participants. The process for the

pretest sample is very similar to the

process for the main survey, with identical sample definitions in both samples.

When the survey items were judged by

the investigators to be functioning as

intended, the final survey was fielded in

May 2012. Eligible participants in the

survey were adults 18 years or older. This

study is based on responses of parents

with children 0 to 5 yearsold in child care.

The study was approved by the University

of Michigan Medical School Institutional

Review Board.

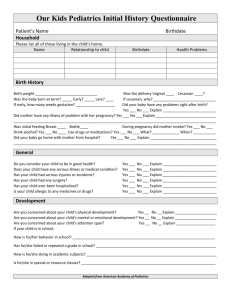

Survey Items

The focus of this study was on parental

responses to 5 questions related to

child care and illness, within a larger

survey of 52 questions on topics including bullying, hearing loss, top child

health concerns in respondents’ communities, and whole genome sequencing. The survey questions related to

child care and illness developed by the

study team are presented in Fig 1: for

purposes of analysis, “child care” also

included “daycare” and “preschool”

settings. Only children who required

care outside their homes were included.

For parents with .1 child, each parent

was asked to select the youngest child

as the index case for purposes of this

study.

e121

Downloaded from by guest on October 1, 2016

FIGURE 1

Survey questions in NPCH survey related to child care illness and management.

e122

HASHIKAWA et al

Downloaded from by guest on October 1, 2016

ARTICLE

Parents completed survey questions

regarding illnesses that caused absence

from child care and medical careseeking behavior when their children

could not attend child care. Five hypothetical vignettes about a child with illness symptoms (cold symptoms without

fever, conjunctivitis, gastroenteritis,

mild fever, and ringworm), adapted

from Copeland et al8 and previously

used by the authors,9,21 were presented

to each respondent (Fig 1). For each of

the illness vignettes, parents chose

whether the child would be a) sent to

child care despite symptoms; b) excluded by child care because of illness;

or c) kept at home even if the child was

allowed at child care. Parents were also

asked if they would take their children

for medical care if their children developed symptoms the evening before

an important parent meeting. The median time to complete the survey was

10 minutes.

Survey Analysis

Deidentified data were presented from

the survey partner to the authors, with

sampling weights on the basis of the US

Census to yield nationally representative estimates. All result data are presented weighted for the US population.

Bivariate analyses (x2 tests) were

conducted for the relationship between parent-reported ED/UC use and

several parent (gender, race, parent

education, household income, house

ownership status, housing type) and

child (insurance status, allergy status,

asthma status, seizure, lung disease

from prematurity, obesity) characteristics. The primary outcome was

parent’s use of either the ED or UC for

their child. Parents’ choices of site of

urgent medical care (ED, UC, or primary care provider) were initially analyzed separately, but UC and ED were

then combined for final analysis, given

the sample size and distribution of

answers.

The authors then applied logistic regression models to examine the associations between parent-reported ED/UC

use and child variables. All variables

achieving a P , .05 level of significance

in bivariate analyses were retained in

our final multivariate model. Descriptive

statistics were used to summarize

responses to vignettes.

RESULTS

Study Participants

Overall survey participation rate was

62%. Among the participating cohort of

parents with children 0 to 5 years old (n =

630), 57% of parents (n = 357) required

child care for at least 1 child, of which

84% (n = 303) of parents had a child

requiring child care outside the home.

Parent and child demographics are

presented in Table 1.

Overall, 38% of parents required

a doctor’s note either for their own

work (20%), and/or so their children

could return to child care (30%). Onethird of parents (33%) were concerned

about loss of job or pay when taking

time off of work to care for their sick

children when those children were

unable to attend child care.

Most parents (88%) took their children

to a medical provider when their sick

children were unable to attend child

care. Although 80% of parents reported

seeking medical care for their sick

child in the past year at a primary care

physician’s office, substantial proportions

of parents also reported choosing UC

(26%) or ED (25%) settings.

Factors Associated With ED/UC

Utilizations: Bivariate Analysis

In bivariate analyses, ED/UC use was

significantly higher among parents

needing a doctor’s note (versus those

who did not), parents with work concerns (versus those without), African

American parents (versus all others),

single/divorced parents (versus married parents); and parents with an-

PEDIATRICS Volume 134, Number 1, July 2014

TABLE 1 Parent and Child Characteristics

Parent and Child Characteristics, N = 303

Parent gender

Women

Men

Parent race/ethnicity

Non-Hispanic white

Non-Hispanic black

Other non-Hispanic

Hispanic

Parent marital status

Married

Living with partner

Never married

Divorced

Separated

Annual household income

,$30K

$30K to $60K

.$60K to #$100K

.$100K

Parent education level

Less than high school

High school

Some college

Bachelor’s degree or higher

Child age

0–11 mo

1y

2y

3y

4y

5y

Time in child care

.30 h per week

10–30 h per week

,10 h per week

Child asthma

Yes

No

Child insurance

Private

Public

None

%

53

47

59

16

6

19

71

13

10

4

2

23

28

27

22

11

21

33

35

7

7

15

18

22

31

31

40

29

8

92

64

33

3

nual household income ,$60 000 (vs

$$60 000). Parent education level,

child insurance status, and other child

variables were not statistically significantly associated with ED/UC use in

our analysis.

Parents’ need for a doctor’s note, parent race/ethnicity, marital status, and

parent work concerns remained statistically significant in multivariate

analyses. ED/UC use was higher among

parents needing a doctor’s note (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 4.2; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.5–11.7). African

American parents were more likely than

e123

Downloaded from by guest on October 1, 2016

white or Hispanic parents to use the

ED/UC (aOR = 4.2; 95% CI: 1.2–14.6).

Single or divorced parents (aOR = 4.3;

95% CI: 1.4–13.5), and parents with job

concerns (loss of pay or job when taking

time off work to care for a sick child

unable to attend child care; aOR = 3.4;

95% CI: 1.2–9.7) were also more likely

to use the ED/UC.

Vignettes and Medical

Care-Seeking Behavior

Collectively across all vignettes, .85%

of parents would seek acute medical

care for their children for any symptoms

presented. Parent responses to illness

vignettes are presented in Fig 2.

FIGURE 2

Will parents send a child with symptoms to child care?

Parent preference for the type of acute

medical care (primary care provider

versus ED/UC versus no visit) also varied

depending on illness symptom in each

vignette (Fig 3).

DISCUSSION

Our survey is the first study to demonstrate that a high proportion of parents

report seeking medical evaluation in

acute care settings when their children’s

illnesses prevent attendance at child

care. The potential impact of this type of

health care-seeking behavior on health

care resources may be substantial

given the sheer number of children

currently using child care services

nationally. Reasons for seeking acute

medical care for a child excluded

from child care may be multifactorial,

with ED/UC use higher among singleparent households, African American

parents, parents concerned about job

threats to their job or job-related income, and parents in need of a doctor’s

note.

Our results concur with previous studies

that revealed factors associated with

nonurgent pediatric emergency visits

include single-parent status and the

need for convenient before- and afterwork hours.27,33 Our additional findings that parents at higher risk for using

e124

FIGURE 3

Parent preference for acute medical care.

ED/UC settings for child care illnesses

were African American parents and

single parents are also consistent with

previous studies.23,25 Our study did not

find that Hispanic families were at higher

risk for ED/UC use, consistent with

studies revealing that Hispanic families are more dependent on child care

provided by extended families.38,39

Parents without sick leave benefits face

a considerable dilemma as they risk

either loss of wages or loss of a job to

stay home with a sick child excluded

from child care. Parents may view the

HASHIKAWA et al

Downloaded from by guest on October 1, 2016

situation as a socioeconomic emergency, choosing the inconvenience of an

urgent medical evaluation over the inability to return to work in a timely

manner. This choice may partially explain why almost 9 of 10 parents in our

study chose to seek medical evaluation

when their sick child could not attend

child care. Lack of health insurance was

not associated with increased ED/UC

use because the majority of children

in our survey, similar to 2011 national

statistics, had health insurance coverage.40

ARTICLE

Child care illness policies that differ

from AAP child care guidelines may impact parent medical care-seeking behavior. The need for a doctor’s note, as

reported by almost one-third of parents

in our survey, was associated with increased ED/UC use for sick children excluded from child care. Many child care

settings, in contrast to AAP guidelines,

require health care visits before a child

can return to child care.21 National AAP

child care guidelines no longer require

a mandatory health visit for many

symptoms of illness and children can

usually return to child care as long as

general exclusion criteria are resolved,

the child can participate in usual activities, and child care providers can provide and maintain safe staffing ratios.19,41

A previous study revealed that the majority of parents of children excluded

from child care reported they would not

have scheduled the medical visit if it

were not required by child care policies.42 Our study revealed that with almost one-third of parents (for fever,

pink-eye, rash, and gastroenteritis

vignettes) reporting their children

would not be allowed in child care, a

substantial proportion of parents may

be scheduling medical visits on the

basis of unnecessary child care illness

exclusion policies. Interventions targeting child care providers to use AAP

guidelines to make appropriate exclusion and return-to-care decisions may

decrease parents’ need to seek urgent

medical evaluation for nonurgent

child care illnesses.

All the illness symptoms in the vignettes,

per AAP child care guidelines, would not

have required immediate exclusion from

child care settings. In our study, few

parents would send their child with mild

symptoms to child care for ringworm,

gastroenteritis, or fever. Most parents

reported wanting to seek acute medical

care for at least 1 of the illnesses in the

vignettes. Moreover, parents’ decisions

to seek urgent medical evaluation varied

by vignette, suggesting parents are

more concerned about certain symptoms (eg, fever, rash) compared with

others. These findings are consistent

with a previous survey of child care

center directors, which reported that

children with these same symptoms

(rash or fever) would be more likely

than children with other symptoms to

be excluded from child care centers.9

Consistent with previous studies,

parents in our national survey reported

self-excluding their children from child

care, suggesting a lack of knowledge regarding AAP national child care guidelines by parents.1,8 We were surprised

by the proportion of parents who

reported they would seek medical care

for mild upper respiratory symptoms,

with almost one-fifth of parents reporting they would seek primary care provider evaluation for their child. Given

the large number of children in child

care settings, parents with sick children

unable to attend child care seeking

acute medical evaluation may profoundly impact available primary care

resources.

Our study also indicates that “fever

phobia,” described for many years in

the literature, continues to exist among

parents.43 Fever education and anticipatory guidance may benefit parents.44

New parents with young children in

child care should be given regular anticipatory guidance regarding the expected

increase in frequency of infections and

the management of common child care

related illnesses. Targeted parent educational interventions in child care could

help decrease the demand for antibiotics

for viral or respiratory conditions.

It is unclear how implementation of the

Affordable Care Act (ACA) may affect

health care-seeking behavior of parents

forchildren in child care. In this study and

others, most families have primary care

providers for their child, and expansion

of children’s coverage is not a major

focus of the ACA. The ACA’s emphasis on

PEDIATRICS Volume 134, Number 1, July 2014

providing care in patient-centered medical homes may encourage providers to

expand service hours, which can help

decrease ED/UC visits for primary careappropriate conditions.

The child care industry and child care

providers face numerous challengeswith

respect to managing illness in child care

settings. Many child care settings are

facedwithhigh-turnoverofstaff,poorpay,

and lack of available health-related

training; children with mild illness may

place a significant strain on child care

provider ratios. Additionally, child care

providers may face considerable opposition from some parents who feel any

illness should be excluded from child

care. To help child care providers establish policies for safe and appropriate

management of mildly ill children, the

AAP has established national recommendations that include guidelines that

allow for exclusion if staff to child ratio is

not adequate or the child cannot participatecomfortablyinactivities. The AAP

has created a new free online learning

course via PediaLink available through

the AAP’s Healthy Child Care America

Web site (http://www.healthychildcare.

org) for child care providers to learn

how to prevent and manage infectious

diseases in child care settings on the

basis of AAP national child care guidelines. Additionally, the AAP Web site offers

free, in-training materials that health

care trainers can use to teach groups of

child care professionals and parents

about AAP national child care illness

guidelines.45 Widespread dissemination

of AAP child care guidelines at the state

and national level along with active child

care provider training has the potential

to decrease parental work absenteeism

and health resource utilization.

Our study has several potential limitations. First, similar to any survey,

selection bias and response bias may

exist. We used an established survey process recognized as valid and nationally

representative in previous peer-reviewed

e125

Downloaded from by guest on October 1, 2016

publications, but it is possible that unforeseen biases related to the perspectivesofparentswithchildreninchild

caremay haveinfluenced thefindings.34–37

Another limitation in our study design

is the use of vignettes to assess decisions about child care attendance and

care-seeking behavior. It is possible that

parents’ responses may not reflect actual

medical care-seeking behavior. Nevertheless, the vignettes provided a standardized approach to assess parents’

care-seeking behavior tendencies, in

a manner aligned with AAP guidelines.

Another potential limitation is that the

languageandstructureofthesurveyitems

may have been challenging for parents

with low literacy. For this reason, we

designed the survey at a Flesch-Kincaid

reading level of 3.1 (third grade); additionally, the vignette items have been

previously and successfully used in a

survey for parents.8 Finally, the fifth vignette presented a situation that may

potentially represent a bias toward parents in professional job settings. The

scenario, however, was intentionally nonspecific (parent faced with an important

meeting the next day) so that the scenario

could still occur for parents employed in

minimum wage or job-training settings

and not just in professional settings.

CONCLUSIONS

A substantial proportion of parents

seek care in ED/UC settings for children excluded from child care for

nonurgent conditions. Socioeconomic

and parent concerns about loss of pay

or job may be significant contributors

to urgent medical care-seeking behavior among parents with sick children unable to attend child care.

Adoption of national AAP child care

guidelines by states and the training of

child care providers and parents may

reduce the unnecessary exclusion of ill

children and the unnecessary utilization of ED/UC resources.

REFERENCES

1. Copeland KA, Duggan AK, Shope TR. Knowledge and beliefs about guidelines for exclusion of ill children from child care.

Ambul Pediatr. 2005;5(6):365–371

2. Shope TR, Aronson S. Improving the health

and safety of children in nonparental early

education and child care. Pediatr Rev. 2005;

26(3):86–95

3. Liu M, Anderson SG. Neighborhood effects

on working mothers’ child care arrangements. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2012;34(4):740–

747

4. Alexander CS, Zinzeleta EM, Mackenzie EJ,

Vernon A, Markowitz RK. Acute gastrointestinal illness and child care arrangements. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;131(1):124–131

5. Marx J, Osguthorpe JD, Parsons G. Day

care and the incidence of otitis media in

young children. Otolaryngol Head Neck

Surg. 1995;112(6):695–699

6. Pickering LK, Bartlett AV, Woodward WE.

Acute infectious diarrhea among children

in day care: epidemiology and control. Rev

Infect Dis. 1986;8(4):539–547

7. Wald ER, Guerra N, Byers C. Upper respiratory tract infections in young children:

duration of and frequency of complications. Pediatrics. 1991;87(2):129–133

8. Copeland KA, Harris EN, Wang NY, Cheng TL.

Compliance with American Academy of

Pediatrics and American Public Health Association illness exclusion guidelines for

child care centers in Maryland: who follows them and when? Pediatrics. 2006;118

e126

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/

content/full/118/5/e1369

Hashikawa AN, Juhn YJ, Nimmer M, et al.

Unnecessary child care exclusions in a

state that endorses national exclusion

guidelines. Pediatrics. 2010;125(5):1003–1009

Pappas DE, Schwartz RH, Sheridan MJ,

Hayden GF. Medical exclusion of sick children from child care centers: a plea for

reconciliation. South Med J. 2000;93(6):

575–578

Shapiro ED, Kuritsky J, Potter J. Policies for

the exclusion of ill children from group day

care: an unresolved dilemma. Rev Infect

Dis. 1986;8(4):622–625

Bell DM, Gleiber DW, Mercer AA, et al. Illness associated with child day care: a

study of incidence and cost. Am J Public

Health. 1989;79(4):479–484

Bradley RH; National Institute of Child

Health and Human Development (NICHD)

Early Child Care Research Network. Child

care and common communicable illnesses

in children aged 37 to 54 months. Arch

Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(2):196–200

Cordell RL, MacDonald JK, Solomon SL,

Jackson LA, Boase J. Illnesses and absence

due to illness among children attending

child care facilities in Seattle-King County,

Washington. Pediatrics. 1997;100(5):850–855

Cordell RL, Waterman SH, Chang A, Saruwatari

M, Brown M, Solomon SL. Provider-reported

illness and absence due to illness among

children attending child-care homes and

HASHIKAWA et al

Downloaded from by guest on October 1, 2016

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

centers in San Diego, Calif. Arch Pediatr

Adolesc Med. 1999;153(3):275–280

Giebink GS. Care of the ill child in day-care

settings. Pediatrics. 1993;91(1 pt 2):229–233

Lu N, Samuels ME, Shi L, Baker SL, Glover

SH, Sanders JM. Child day care risks of

common infectious diseases revisited.

Child Care Health Dev. 2004;30(4):361–368

Wald ER, Dashefsky B, Byers C, Guerra N,

Taylor F. Frequency and severity of infections in day care. J Pediatr. 1988;112(4):540–

546

National Partnership for Women and Families. Paid sick days. Available at: http://

paidsickdays.nationalpartnership.org/site/

PageServer?pagename=psd_toolkit_factsheets.

Accessed April 15, 2014

American Academy of Pediatrics, American

Public Health Association, National Resource Center for Health and Safety in

Child Care and Early Education. Caring for

Our Children: National Health and Safety

Performance Standards; Guidelines for

Early Care and Education Programs. 3rd

ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy

of Pediatrics; Washington, DC: American

Public Health Association; 2011

Hashikawa AN, Stevens MW, Juhn YJ, et al.

Self-Report of Child Care Directors Regarding Return-to-Care. Pediatrics. 2012;

130(6):1046–1052

Landis SE, Earp JA. Day care center illness:

policy and practice in North Carolina. Am J

Public Health. 1988;78(3):311–313

ARTICLE

23. Heymann SJ, Earle A. The impact of welfare

reform on parents’ ability to care for their

children’s health. Am J Public Health. 1999;

89(4):502–505

24. Heymann SJ, Earle A, Egleston B. Parental

availability for the care of sick children.

Pediatrics. 1996;98(2 pt 1):226–230

25. Heymann SJ, Toomey S, Furstenberg F. Working parents: what factors are involved in

their ability to take time off from work when

their children are sick? Arch Pediatr Adolesc

Med. 1999;153(8):870–874

26. Voigt RG, Johnson SK, Hashikawa AH, et al.

Why parents seek medical evaluations for

their children with mild acute illnesses.

Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2008;47(3):244–251

27. Phelps K, Taylor C, Kimmel S, Nagel R, Klein

W, Puczynski S. Factors associated with

emergency department utilization for nonurgent pediatric problems. Arch Fam Med.

2000;9(10):1086–1092

28. Mistry RD, Hoffmann RG, Yauck JS, Brousseau

DC. Association between parental and

childhood emergency department utilization. Pediatrics. 2005;115(2). Available at:

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/115/2/

e147

29. Fong C. The influence of insurance status

on nonurgent pediatric visits to the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6

(7):744–748

30. McCaig LF, Nawar EW. National Hospital

Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2004 emergency department summary. Adv Data. 2006;

(372):1–29

31. Stanley R, Zimmerman J, Hashikawa C,

Clark SJ. Appropriateness of children’s

nonurgent visits to selected Michigan

emergency departments. Pediatr Emerg

Care. 2007;23(8):532–536

32. Zimmer KP, Walker AR, Minkovitz CS, Zimmer

KP, Walker AR, Minkovitz CS. Maternal and

child factors affecting high-volume pediatric

emergency department use. Pediatr Emerg

Care. 2006;22(5):301–308

33. Doobinin KA, Heidt-Davis PE, Gross TK,

Isaacman DJ. Nonurgent pediatric emergency department visits: Care-seeking

behavior and parental knowledge of insurance. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003;19(1):

10–14

34. Tarini BA, Singer D, Clark SJ, Davis MM.

Parents’ concern about their own and their

children’s genetic disease risk: potential

effects of family history vs genetic test

results. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162

(11):1079–1083

35. Dempsey AF, Singer DD, Clark SJ, Davis MM.

Adolescent preventive health care: what do

parents want? J Pediatr. 2009;155(5):689–

694

36. Clark SJ, Butchart A, Kennedy A, Dombkowski KJ. Parents’ experiences with and

preferences for immunization reminder/

recall technologies. Pediatrics. 2011;128

(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/

content/full/128/5/e1100

37. Freed GL, Clark SJ, Butchart AT, Singer DC,

Davis MM. Parental vaccine safety concerns

in 2009. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):654–659

PEDIATRICS Volume 134, Number 1, July 2014

38. Radey M, Brewster KL. The influence of

race/ethnicity on disadvantaged mothers’

child care arrangements. Early Child Res Q.

2007;22(3):379–393

39. Yesil-Dagli U. Center-based childcare use by

Hispanic families: Reasons and predictors.

Child Youth Serv Rev. 2011;33(7):1298–1308

40. Federal Interagency Forum on Child and

Family Statistics. America’s Children: Key

National Indicators of Well-being, 2013

Health Insurance Coverage. Available at:

www.childstats.gov/americaschildren/care1.

asp. Accessed March 1, 2014

41. Aronson SS. Managing Infectious Diseases

in Child Care and Schools, 2nd ed. Elk

Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009

42. Shope TR, Duggan A, Wilson M. Mandatory

doctor’s visits and notes for mildly ill children excluded from child care centers.

Baltimore, MD: Pediatric Academic Societies; 2001

43. Crocetti M, Moghbeli N, Serwint J. Fever

phobia revisited: have parental misconceptions about fever changed in 20 years?

Pediatrics. 2001;107(6):1241–1246

44. O’Neill-Murphy K, Liebman M, Barnsteiner

JH. Fever education: does it reduce parent

fever anxiety? Pediatr Emerg Care. 2001;17

(1):47–51

45. American Academy of Pediatrics. Healthy

Futures: Improving Health Outcomes for

Young Children. Available at: www.healthychildcare.org/healthyfutures.html. Accessed

April 15, 2014

e127

Downloaded from by guest on October 1, 2016

Emergency Department and Urgent Care for Children Excluded From Child

Care

Andrew N. Hashikawa, David C. Brousseau, Dianne C. Singer, Achamyeleh

Gebremariam and Matthew M. Davis

Pediatrics 2014;134;e120; originally published online June 23, 2014;

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2013-3226

Updated Information &

Services

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

/content/134/1/e120.full.html

References

This article cites 39 articles, 15 of which can be accessed free

at:

/content/134/1/e120.full.html#ref-list-1

Citations

This article has been cited by 2 HighWire-hosted articles:

/content/134/1/e120.full.html#related-urls

Subspecialty Collections

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in

the following collection(s):

Emergency Medicine

/cgi/collection/emergency_medicine_sub

Adolescent Health/Medicine

/cgi/collection/adolescent_health:medicine_sub

Toxicology

/cgi/collection/toxicology_sub

Advocacy

/cgi/collection/advocacy_sub

Child Care

/cgi/collection/child_care_sub

Permissions & Licensing

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures,

tables) or in its entirety can be found online at:

/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

Reprints

Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

PEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

publication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned, published,

and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point Boulevard, Elk

Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright © 2014 by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All

rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.

Downloaded from by guest on October 1, 2016

Emergency Department and Urgent Care for Children Excluded From Child

Care

Andrew N. Hashikawa, David C. Brousseau, Dianne C. Singer, Achamyeleh

Gebremariam and Matthew M. Davis

Pediatrics 2014;134;e120; originally published online June 23, 2014;

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2013-3226

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

located on the World Wide Web at:

/content/134/1/e120.full.html

PEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

publication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned,

published, and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point

Boulevard, Elk Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright © 2014 by the American Academy

of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.

Downloaded from by guest on October 1, 2016