Information as a Commodity: New Imperatives of Commercial Law

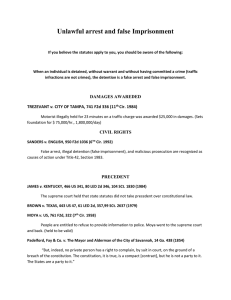

advertisement