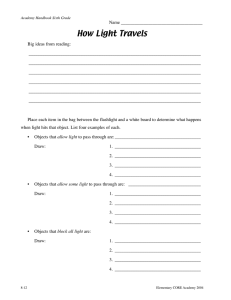

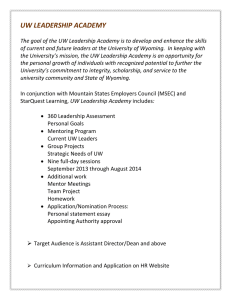

Contextualised learning examples

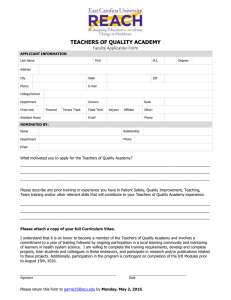

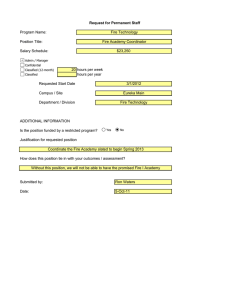

advertisement