WWTW Queensland recommendations report

advertisement

Whistleblowing legislation in Queensland The agenda for reform A J Brown Griffith University Final Report to the Queensland Government of the Australian Research Council Linkage Project: Whistling While They Work: Enhancing the Theory and Practice of Internal Witness Management in Public Sector Organisations September 2009 Contents The author ..................................................................................................................... ii

Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................... ii

Summary of recommendations ....................................................................................... iii

Part I. Background ........................................................................................................ 1

1. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1

2. The research ............................................................................................................. 2

3. Whistleblowers Protection Act 1994 (Qld) in context ............................................. 4

Part II. Reform of Whistleblowers Protection Act 1994 (Qld)..................................... 9

1. Objectives and title................................................................................................... 9

2. Subject matter of disclosure ................................................................................... 11

3. Person making disclosure....................................................................................... 12

4. Receipt of disclosure .............................................................................................. 14

5. Recording and reporting......................................................................................... 15

6. Acting on a disclosure............................................................................................ 15

7. Oversight agency.................................................................................................... 17

8. Confidentiality........................................................................................................ 20

9. Protection of person making disclosure ................................................................. 21

10. Disclosure outside an agency ............................................................................... 22

11. Agency responsibility to ensure protection.......................................................... 26

12. Remedial action.................................................................................................... 28

12. Remedial action.................................................................................................... 28

13. Ongoing assessment and protection ..................................................................... 34

Part III. Restoring Queensland as national leader .................................................... 35

1. Non-whistleblower complainants and informants –

consistent, but separate justice............................................................................ 35

2. Private sector whistleblower protection – taking the initiative.............................. 40

References ...................................................................................................................... 47

Appendix 1 – Select Queensland complainant and

witness protections (all complainants) ............................................................... 49

ii

The author A J Brown is John F Kearney Professor of Public Law, Griffith Law School, Griffith

University, and project leader of the Australian Research Council Whistling While They

Work project.

His former roles include Senior Investigation Officer, Commonwealth Ombudsman

(1993-1997); Associate to Justice G E 'Tony' Fitzgerald AC, President, Queensland Court

of Appeal (1998); and Ministerial Policy Advisor to the Hon Rod Welford MLA,

Minister for Environment, Heritage and Natural Resources, Queensland Government

(1998-99).

He is also a former Senior Research Fellow and Director of the Integrity and Corruption

Research Program, Key Centre for Ethics Law Justice and Governance, Griffith

University; and was lead author of Chaos or Coherence? Strengths, Opportunities and

Challenges for Australia's Integrity Systems (2005), the Final Report of the National

Integrity Systems Assessment (NISA), published by Griffith University and

Transparency International.

Email A.J.Brown@griffith.edu.au.

Acknowledgements This report was produced as part of the national research project ‘Whistling While

They Work: Enhancing the Theory and Practice of Internal Witness Management in

the Australian Public Sector’ (see www.griffith.edu.au/whistleblowing). This

research was made possible by support from the Australian Research Council

(Linkage Project LP0560303) and the partner organisations to the project:

Commonwealth

Commonwealth Ombudsman

Australian Public Service Commission

New South Wales

Independent Commission Against Corruption

New South Wales Ombudsman

Queensland

Crime & Misconduct Commission

Queensland Ombudsman

Public Service Commission

Western Australia

Corruption & Crime Commission

Ombudsman Western Australia

Office of the Public Sector Standards

Commissioner

Victoria

Ombudsman Victoria

Northern Territory

Commissioner for Public Employment

Australian Capital Territory

Chief Minister’s Department

Non-government partner

Transparency International Australia

The author thanks all project partners, colleagues on the project research team, and

participating agencies for their support and direct and indirect contributions to these

results. The findings and views expressed are those of the author and do not

necessarily represent the views of the Australian Research Council or the partner

organisations in the project.

Whistleblowing Legislation in Queensland: The Agenda for Reform iii

Summary of recommendations Reform of Whistleblowers Protection Act 1994 (Qld)

1. Objectives and title

No major

reform needed

Reform

needed

Reform

imperative

2.

Subject matter of disclosure

No major

reform needed

Reform

needed

Reform

imperative

3.

Person making disclosure

No major

reform needed

Reform

needed

Reform

imperative

4.

Receipt of disclosure

No major

reform needed

Reform

needed

Reform

imperative

5.

Recording and reporting

No major

reform needed

Reform

needed

Reform

imperative

6.

Acting on a disclosure

No major

reform needed

Reform

needed

Reform

imperative

7.

Oversight agency

No major

reform needed

Reform

needed

Reform

imperative

8.

Confidentiality

No major

reform needed

Reform

needed

Reform

imperative

9.

Protections for disclosure

No major

reform needed

Reform

needed

Reform

imperative

10. Disclosure outside an agency

No major

reform needed

Reform

needed

Reform

imperative

11. Agency responsibility to protect

No major

reform needed

Reform

needed

Reform

imperative

12. Remedial action

No major

reform needed

Reform

needed

Reform

imperative

13. Ongoing assessment and protection

No major

reform needed

Reform

needed

Reform

imperative

Objectives and title

Recommendation 1. That s 3 of the Act be amended to state its legislative objectives

in terms similar to s 3 of the Protected Disclosures Act 1995 (NSW)

Recommendation 2. That the Act be retitled the Public Interest Disclosure Act.

iv

Subject matter of disclosure

Person making disclosure

Recommendation 3. That Part 3 of the Act be amended to provide that a public

interest disclosure on any matter may be made by:

• a public contractor (in respect of their contracts or the public agency with

which they contract), an employee of a public contractor (in respect of the

delivery of publicly-funded services by the contractor, or the public agency

with which their employer contracts), or a volunteer who is de facto an

unpaid public official or employee of a public contractor; or

• a public officer, public contractor, employee of a public contractor, or public

volunteer who has ceased to work in that capacity or hold that contract.

Further, that if the Commonwealth proceeds with a 'deeming' provision for who may

make a public interest disclosure, consideration be given to including such a

provision in the Queensland Act.

Recommendation 4. That s 14(2) of the Act be amended to provide that a disclosure

will trigger the Act, either (a) if the person making it honestly believes on reasonable

grounds that the information tends to show the conduct or danger, or (b) if the

information does tend to show relevant conduct or danger, irrespective of what the

person believed it to show at the time they made the disclosure.

Receipt of disclosure, Recording and reporting

Acting on a disclosure

Recommendation 5. That a new Part 5 be inserted in the Act (also replacing the

current ss 30-32) providing minimum duties and standards for the assessment and

investigation of disclosures under the Act, for the provision of information about

action taken to persons who make disclosures, and for public and parliamentary

reporting on the Act's operation.

Oversight agency

Recommendation 6. That a new Part be inserted in the Act (also replacing the

current s 31) establishing a new framework for oversight and coordination of the

implementation of the Act, including a designated agency or unit with a

clearinghouse and quality assurance role for individual investigations, and

responsibility to promote, support and require best practice agency whistleblowing

programs.

Confidentiality

Recommendation 7. That sub-section 55(3) of the Act be amended to provide that a

person may make a record of confidential information or disclose it to someone else,

for purposes including the protection of any person under the Act, including a person

who has made a public interest disclosure – provided that information which

identifies or could tend to identify a person who has made a public interest

disclosure may only be disclosed with the prior, informed consent of that person, or,

if consent is impossible to obtain, where the interests of that person are not harmed

and there is reasonable excuse to do so.

Whistleblowing Legislation in Queensland: The Agenda for Reform v

Protections for person making disclosure

Recommendation 8. That sub-s 42(1) of the Act be amended to provide that 'any

person' – not just 'a public officer' – who takes a reprisal commits an offence.

Disclosure outside an agency

Recommendation 9. That a new section be inserted in the current Part 5 of the Act,

to the effect that ss 39-43 of the Act will also apply to a public interest disclosure

made to a third party, including a journalist, where the matter:

• has already been disclosed internally to the agency concerned and to an

external integrity agency of government, or to an external integrity agency

alone, and not been acted on in a reasonable time having regard to the nature

of the matter; or

• is exceptionally serious, and special circumstances exist such as to make prior

disclosure, internally or to an external integrity agency, impossible or

unreasonable (for example, in some circumstances involving serious and

immediate threat to public health or safety).

Agency responsibility to ensure protection

Recommendation 10. That s 44 of the Act be replaced with a new, more detailed

section providing that:

•

it is the responsibility of the CEO and management of each agency to ensure

that appropriate action is taken on all public interest disclosures, and that

appropriate support and protection is provided to employees; and

•

each agency must develop and implement a whistleblowing program which

addresses all the requirements in principle 11, the Australian Standard, and

the guidelines or model code developed by the oversight agency.

Remedial action

Recommendation 11. That s 43 of the Act be amended to provide that:

•

Damages may also be sought against any person who, through act or

omission, fails to take reasonable steps to protect a person from detriment

that could reasonably be foreseen to befall them as a result of a person

having made a public interest disclosure;

•

The liability of a person or organisation under s 43 is unaffected by the fact

that any person (including the defendant, or an employee or person under the

control of the defendant) has been, or could be, prosecuted for an offence

under s 42; and

•

Neither the liability of a person or organisation under s 43, or any other right

of compensation created by the Act, nor the procedure by which a person

may seek damages under those sections, are affected by the fact that the same

or similar damages may have been sought under any other legislation

(including workers' compensation legislation), provided that the same

damages may not be sought twice.

vi

Further, that a new Part be inserted in the Act, creating:

•

A right for a current or current public officer, public contractor, or employee

of a public contractor, to seek damages in the Queensland Industrial

Relations Commission against an employing or contracting public agency, of

no limit, for any act or omission (including but not limited to wrongful

dismissal) which caused or contributed to damage or loss on the part of the

employee or contractor because they did, or might make a public interest

disclosure;

•

An obligation on public agencies to make an ex gratia payment of

compensation or other appropriate restitution to any public officer or public

contractor whom it is reasonably satisfied has suffered damage or loss

because they did, or might make a public interest disclosure, irrespective of

whether the person has availed themselves of the above right to

compensation (but with any such compensation or restitution to be counted

against any later award for compensation); and

•

A power and obligation on the oversight agency to take action on behalf of

any public officer or public contractor whom it is reasonably satisfied has

suffered damage or loss because they did, or might make a public interest

disclosure, in respect of whom no reasonable compensation or restitution

has been made, with the consent of that person.

Ongoing assessment and protection

Recommendation 12. That the statutory requirements for minimum procedures in

recommendation 10 include a requirement for ongoing assessment of the welfare of

public officers who have made a public interest disclosure.

Restoring Queensland as national leader 1. Non-whistleblower complainants and informants –

consistent, but separate justice

Recommendation 13. That the Queensland Government commission a public review

of the extent and adequacy of general protections for complainants, informants and

other witnesses under Queensland legislation, separately to its reforms to the

Whistleblower Protection Act 1994, with a view to further reforms aimed at ensuring

best practice in public complainant protection.

Further, that once amendments have been introduced into other relevant Queensland

legislation to bring it into line with best practice in public complainant protection –

including environmental protection, public health and safety, and disability services

legislation – that protections for 'any person' who makes a public interest disclosure

on these matters be transferred from the Whistleblower Protection Act 1994 to more

appropriate legislation.

Whistleblowing Legislation in Queensland: The Agenda for Reform vii

2. Private sector whistleblower protection –

taking the initiative

Recommendation 14. That the Queensland Government show leadership in the field

of private sector whistleblower protection, by initiating a joint State Government-led

project through a mechanism such as the Council for Australian Federation, seeking

the support and participation of the Commonwealth Government, to identify the key

principles and legislative strategies needed for an effective, comprehensive, national

regime for the protection of public interest whistleblowers in Australia's nongovernment sectors.

Whistleblowing Legislation in Queensland: The Agenda for Reform 1

Part I. Background 1. Introduction This report sets out recommendations for the reform of whistleblowing legislation in

Queensland, as well as review of associated legislation in Queensland and, where

relevant, nationally.

The report focuses on the reforms that are necessary to rectify proven deficiencies in

Queensland's public integrity framework, and desirable to restore Queensland to a

national leadership role on issues of integrity and accountability generally.

The report states key lessons for Queensland from the national research project,

Whistling While They Work: Enhancing the Theory and Practice of Internal Witness

Management in Public Sector Organisations (2005-2009), led by Griffith University.

The Queensland Government played a major part in initiating this research, and was

a major contributor and participant in the project.

The report is also a submission in response to the Queensland Government Green

Paper, Integrity and Accountability in Queensland (August 2009, pp.25-26). In

particular, it seeks to help answer the question (p.26):

How could the current legislative protections for whistleblowers be enhanced?

As acknowledged in the Green Paper, the Whistling While They Work project has

already published several national reports which serve as background to this

Queensland report. They include:

•

Public Interest Disclosure Legislation in Australia: Towards the Next Generation

(Brown 2006). An issues paper published by the Commonwealth, NSW and

Queensland Ombudsman, comparing whistleblowing legislation nationally.

•

Whistleblowing in the Australian Public Sector (Brown 2008). The first report of

the Whistling While They Work project, published by the Australia & New

Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG) and ANU E-Press.

•

Whistling While They Work: Towards best practice whistleblowing programs in

public sector organisations (Roberts et al 2009). The draft second report of the

project, released at the 2nd Australian Public Sector Anti-Corruption Conference,

Brisbane, July 2009.

This report draws on research results, findings and conclusions contained in the

above reports.

In general, the Whistling While They Work research has confirmed the absolute

importance of effective whistleblowing programs for integrity and accountability in

the public sectors studied. It has also confirmed both the utility and the importance

of robust, well-designed whistleblowing legislation to provide the necessary

framework to support those programs.

2

Accordingly, this report will not repeat the case for effective whistleblowing

programs and legislation, other than as necessary to justify a specific reform.

The Whistling While They Work research team commends the Queensland

Government for publishing the current green paper, and for taking a holistic

approach to the review and development of Queensland's public integrity system.

We trust this report will assist in resolving some of the most complex, and in some

cases overdue issues going to the heart of public integrity.

What is 'whistleblowing'? In this report:

•

'whistleblowing is taken to mean the 'disclosure by organisation members

(former or current) of illegal, immoral or illegitimate practices under the

control of their employers, to persons or organisations that may be able to

effect action' (Miceli & Near 1984: 689; see Brown 2008: 8-13);

•

'whistleblowing' also means 'public interest' whistleblowing – that is,

disclosures about suspected or alleged wrongdoing which affects more than

simply the personal or private interests of the person making the disclosure,

while noting that such disclosures may well also include such interests;

•

'whistleblower' means only a person who discloses wrongdoing by or within

an organisation of which they are a member, or with which they have a

privileged or special relationship such as to mean their disclosure comes

'from within' (e.g. former employees, contractors, employees of contractors,

volunteers); and

•

other persons who disclose suspected or alleged wrongdoing, who are not

members of the organisation about which they are disclosing, are defined as

other 'complainants', 'informants' or 'witnesses'.

These definitions have significant implications for unscrambling some of the current

deficient aspects of Queensland's whistleblower protection regimes, and restoring

Queensland to a position of leadership in integrity system best practice.

2. The research As discussed in the Green Paper, the Whistling While They Work project has been a

four-year collaborative research project funded by the Australian Research Council

and 14 partners, including three Queensland Government agencies: the Crime and

Misconduct Commission, Queensland Ombudsman and Public Service Commission.

Together these agencies contributed $141,027 to the project on behalf of the

taxpayers of Queensland, in addition to substantial in-kind contributions and

participation, within an overall national project budget of $1.01 million. The project

is believed to be the most comprehensive empirical study of whistleblowing, and the

largest per capita, conducted to date worldwide.

Table 1 summarises the survey-based research conducted as part of the project.

Whistleblowing Legislation in Queensland: The Agenda for Reform 3 Table 1. Quantitative research, Whistling While They Work project (see Brown 2008: 16)

Short title

Full title

No. of

items

Cth

No. of participating agencies

a

NSW

Qld

WA

Total

1. Agency Survey

Survey of Agency Practices and

Procedures (2005)

42

73

85

83

63

304

2. Procedures Assessment

Assessment of Comprehensiveness

of Agency Procedures (2006-07)

24

56

60

31

28

175

3. Employee Survey

Workplace Experiences and

Relationships Questionnaire

(2006-07)

50

27

34

32

25

118

Surveys distributed

5,545

8,324

6,343

2,965

--

Responses

2,307

2,561

1,729

1,007

--

(25)

(31)

(29)

(17)

(102)

(Procedures Assessment &

Employee Survey)

Total

surveys

Total

responses

23,177

7,663 b

4. Internal Witness Survey b

Internal Witness Questionnaire

(2006-07)

82

4

4

4

3

15

455

240

5. Casehandler Survey c

Managing the Internal Reporting of

Wrongdoing Questionnaire (2007)

77

4

5

4

3

16

1,651

315

6. Manager Survey c

Managing the Internal Reporting of

Wrongdoing Questionnaire (2007)

77

4

5

4

3

16

3,034

513

7. Integrity Agency Survey

Survey of Integrity Agency

Practices and Procedures (2007)

45

5

5

3

3

16

8. Integrity Casehandler Survey

Managing Disclosures by Public

Employees Questionnaire (2007)

75

3

3

3

3

12

304

82

a

Throughout this report, Cth figures include a range of both APS (Australian Public Service) and non-APS agencies unless otherwise indicated.

includes 59 responses for which jurisdiction/agency unknown.

c

indicates written questionnaire response to be followed up by qualitative interview in willing cases (case study agencies)

b

4

Among the total of 304 Commonwealth, NSW, Queensland and Western Australian

agencies, a total of 83 Queensland Government agencies participated in the research.

This includes the 32 Queensland agencies (and over 1,700 individual public servants)

who participated in the major Workplace Experiences and Relationships

Questionnaire; and the four Queensland organisations who participated in the

national group of 16 agencies, as 'case study' agencies for closer evaluation of their

whistleblowing systems and procedures.

Further details of the research, and the features of the participating agencies, are set

out in the first and second reports (Brown 2008: 4-21; Roberts et al 2008: 14-20).

3. Whistleblowers Protection Act 1994 (Qld) in context History Historically, Queensland was the first Australian jurisdiction to provide legislative

protection to whistleblowers, in the wake of the Fitzgerald Inquiry (Whistleblowers

(Interim Protection) and Miscellaneous Amendments Act 1990 (Qld)).

Subsequently, following a public inquiry by the Queensland Electoral and

Administrative Review Commission (EARC 1991), the Queensland Parliament

enacted the Whistleblowers Protection Act 1994 (Qld).

Today, all Australian State and Territory jurisdictions possess public sector

whistleblowing legislation of some kind (Brown 2006). The exception has been the

Commonwealth Government, although recommendations for federal legislation as

well as Private Members Bills have been in existence since 1994 (see Senate 1994).

At the Commonwealth level, the Rudd Government has now committed to 'provide

best-practice legislation to encourage and protect public interest disclosure' (ALP

2007), and is preparing its response to a House of Representatives Standing

Committee report on how to do so (House of Representatives 2009).

In Queensland, the EARC Report remains an authoritative guide to many of the

major issues of legislative design involved in such legislation today. The resulting

legislation was, and remains, the most detailed special-purpose whistleblowing

legislation in Australia, and one of the most detailed such Acts in the world.

However, the fact that Queensland's legislation is detailed, including best practice

provisions in some key respects, does not mean that its legislative approach ever

reflected best practice in all key respects.

Moreover, national and international comparisons, combined with the empirical

evidence gathered by the Whistling While They Work project, indicate that:

•

The Whistleblowers Protection Act 1994 (Qld) has now been surpassed

nationally and internationally in relation to several of the most important

features of statutory whistleblowing regimes;

•

Implementation of the Act has fallen short of original objectives; and

•

New questions have arisen about how whistleblower protection should fit

within the wider public and private sector integrity systems.

Whistleblowing Legislation in Queensland: The Agenda for Reform 5 Table 2. Main legal effects of whistleblowing legislation compared

No.

Type of legal effect

1.

Obligations on organisations/employers, and others, to

receive and act upon public interest disclosures by

organisation members

2.

3.

Obligations on organisations/employers to provide and

maintain a safe and non-discriminatory working

environment for organisation members who make public

interest disclosures, including support and protection

Defences against liability for disciplinary, criminal or

civil actions that might be taken against an organisation

member as a result of their disclosure (e.g. breach of

instruction or confidence, disclosure of secrets,

defamation)

4.

Criminalisation of reprisals against persons as a result of

a disclosure by an organisation member

5.

Rights of compensation for organisation members who

suffer damage or loss to themselves or their career for

making a disclosure

Whistleblowers

Protection Act

1994 (Qld)

How Queensland Act compares with

other Australian

legislation

US federal

legislation

Weaker than some (within

strong overall integrity

framework)

Slightly stronger

(but US amendments

likely to strengthen)

Slightly stronger

(but UK provides

stronger incentives)

s 44

Weaker than several

Stronger

(but US amendments

likely to strengthen)

Slightly stronger

(but UK provides

stronger incentives)

s 39

Weaker than NSW and

proposed Cth (disclosures

to media not protected)

Weaker

(disclosures to media

protected in US

Weaker

(disclosures to media

protected in UK)

Slightly weaker than most

(only reprisals by public

officials are prosecutable)

Slightly weaker

(only reprisals by

public officials are

prosecutable)

Stronger

(no criminal offence

of reprisal in UK)

Slightly stronger in one

respect (IRC); similar/

weaker in others

Similar

(but US amendments

likely to strengthen)

Weaker

ss 29, 30

s 42

s 43

UK legislation

6

As shown in Table 2 above, contemporary whistleblowing legislation uses five basic

types of legal obligation and/or remedy to encourage and protect public interest

whistleblowing, as an element of modern integrity systems.

The research showed that the approaches used in Queensland for achieving these

effects, and the framework in which they are embedded, have not led to best practice

outcomes. Despite the historical importance, relative sophistication and profile of

Queensland's legislation, the state recorded:

•

Lower overall confidence in relevant legislation among public employees,

than in the other three jurisdictions studied;

•

Lower overall trust among public employees, as to how they would expect

the management of their agency to respond to an employee report of

wrongdoing, than in the other three jurisdictions studied;

•

Lower average outcomes in terms of the perceptions of whistleblowers as to

how they were treated by the management of their agencies, than in NSW or

Western Australia (but the same outcome as for Commonwealth employees,

who have no comprehensive whistleblowing legislation); and

•

Lower average comprehensiveness in agency whistleblowing procedures,

than in the other three jurisdictions studied (Roberts 2008: 240, 249).

These results will be further referred to in Part II.

Table 2 also shows how the Whistleblowers Protection Act 1994 (Qld) currently

compares with legislative best practice in other Australian jurisdictions, the United

States and United Kingdom, on each of these key features. More detailed

comparison will be referred to in Parts II and III (see also Brown 2006). However it

is useful at the outset, to note the broad ways in which Queensland and other

Australian approaches currently differ from the main international approaches.

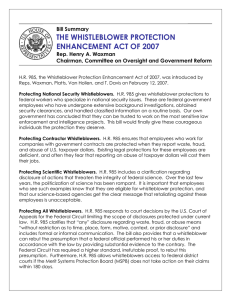

The United States approach As in Australia, whistleblower protection in the USA commenced as a public

integrity measure beginning, federally, with the Civil Service Reform Act 1978 (US),

followed by the Whistleblower Protection Act 1989 (US). There are many equivalent

State statutes.

The federal US approach provided legal protections to, and made it illegal to

undertake reprisals against, public sector whistleblowers who disclose 'a violation of

any law, rule, or regulation' or 'gross mismanagement, a gross waste of funds, an

abuse of authority, or a substantial and specific danger to public health or safety'. 1

The protections apply for any such disclosure made 'to the Special Counsel or to the

Inspector General of an agency or another employee designated by the head of the

agency to receive such disclosures of information' (i.e. disclosures to an integrity

agency and internal disclosures). 2

1

Whistleblower Protection Act 1989 (Title 5 US Code), Sec. 1213(a).

2

Whistleblower Protection Act 1989 (Title 5 US Code), Sec. 1213(a). Subsection 2.

Whistleblowing Legislation in Queensland: The Agenda for Reform 7

The protections also apply to any other such disclosure – for example, disclosures to

the media – where 'not specifically prohibited by law and if such information is not

specifically required by Executive order to be kept secret in the interest of national

defense or the conduct of foreign affairs'. 3

Queensland's legislation differed consciously from the U.S. approach by:

•

Providing more detailed systems to encourage internal disclosures and

disclosures to integrity agencies, thereby

•

Removing the need for legal protections to extend to external, public or

media disclosures, because if government's internal processes worked, this

should not be needed.

US whistleblowing legislation has itself been subject to many calls for reform. At

time of writing, two Whistleblower Protection Enhancement Bills are in the U.S.

Congress and are expected to be consolidated, passed and signed into law by

President Barak Obama. Once consolidated, these Bills will:

•

Catch up with Australian approaches by providing more detailed systems to

encourage internal disclosures and disclosures to integrity agencies;

•

Catch up with United Kingdom approaches by providing more effective

avenues for compensating mistreated whistleblowers (see below); and

•

Strengthen the protection for whistleblowers who go public, by removing the

preclusion against public disclosures by 'national security' employees.

The United Kingdom approach Four years after the Queensland Act, Britain enacted whistleblowing legislation

which differed from the US or Australian approaches in key aspects. The British

approach has since been followed in a range of countries including South Africa and

Japan. The main differences were:

•

To create a scheme applying equally to the public sector and the private

sector, through national employment law – i.e. the Public Interest Disclosure

Act 1998 (UK) embedded whistleblower protection in the Employment Rights

Act 1996 (UK) rather than creating stand-alone legislation; and

•

To focus almost solely on driving better organisational responses and

protection of employees, by providing effective avenues for compensating

mistreated whistleblowers (through the national Employment Appeals

Tribunal system, the equivalent of Fair Work Australia).

The UK approach differed from US and Australian approaches, in creating no

criminal offence of reprisal against a whistleblower.

The UK approach nevertheless followed the US approach in still extending

protection to most whistleblowers who go public – leaving Australian jurisdictions

such as Queensland as the only ones where, in the main, this cannot occur.

3

Whistleblower Protection Act 1989 (Title 5 US Code), Sec. 1213(a). Subsection 1.

8

In summary In short, Queensland legislation never matched some of the original US provisions,

while surpassing others. The UK then leapfrogged both Australia and the US in key

respects, while matching the US in others. The US is now looking to catch up with

best practice where found in Australia or the UK, while further strengthening those

provisions on which it was always strong.

The overall result is that Queensland (and other Australian jurisdictions) has now

either been left behind, or stands to be left behind in key respects, by comparison

with US and/or UK approaches. The empirical research results confirm this.

Fortunately, Queensland is in a strong position to rectify known deficiencies, regain

its position as both a national and world leader in the quality of its whistleblower

protection regime, and take a new leadership role in the resolution of the 'next

generation' of challenges in the field of whistleblower protection.

Part II of this report accordingly sets out specific recommendations to bring the

Whistleblowers Protection Act 1994 (Qld) into line with current and foreseeable best

practice, as informed by the research.

'Best practice' in this context is defined as legislation which meets, to a high level,

the 13 principles proposed in chapter 11 of the first project report: 'Best Practice

Whistleblowing Legislation for the Public Sector: The Key Principles' (Brown et al

2008). These principles were developed jointly by: the author, Associate Professor

Paul Latimer (Monash University), Professor John McMillan (Commonwealth

Ombudsman) and Mr Chris Wheeler (Deputy NSW Ombudsman), in consultation

with other project team members and partners.

Professor McMillan also served as an engaged consultant to EARC in its original

inquiry into whistleblowing legislation in Queensland (see EARC 1991: 8).

Part III of this report sets out further recommendations for the contribution that

Queensland can make to resolving the relationship between the State's primary public

sector whistleblowing legislation, and:

•

protection of other complainants, informants and witnesses; and

•

protection of whistleblowers in the private and civil society sectors, not just

in Queensland but nationally.

Whistleblowing Legislation in Queensland: The Agenda for Reform 9

Part II. Reform of Whistleblowers Protection Act 1994 (Qld) Each key principle of legislative best practice as stated below [boxed] is taken from

'Best Practice Whistleblowing Legislation for the Public Sector: The Key Principles'

(Brown et al 2008).

1. Objectives and title The stated objectives of public interest disclosure legislation should be:

• to support public interest whistleblowing by facilitating disclosure of

wrongdoing

• to ensure that public interest disclosures are properly assessed, and where

necessary investigated and actioned

• to ensure that a person making a public interest disclosure is protected against

detriment and reprisal.

These objectives should be captured in the short and long title to the legislation.

Public Interest Disclosure Act is a preferred title to ‘Whistleblower Protection Act’

or ‘Protected Disclosures Act’.

No major reform

needed

Reform

needed

Reform

imperative

Currently, the principal purpose of the Act (s 3) focuses on the protection of persons

who make public interest disclosures under the Act, as if this is all the Act intends to

achieve and indeed, as if this is an end in itself. This is somewhat misrepresentative.

Better legislative practice is to incorporate the vital protection objective of the Act in

a statement which also recognises the overall purpose of whistleblowing itself

(public sector integrity and the identification and rectification of wrongdoing), and

also makes explicit the Parliament's intention that disclosures will be appropriately

acted upon, under this Act if not under other legislation.

It is noted that EARC's original proposals included a better statement of legislative

objectives than the one enacted (EARC 1991: A5). Current best legislative practice

in Australia is provided by s 3 of the Protected Disclosures Act 1995 (NSW).

Recommendation 1. That s 3 of the Act be amended to state its legislative

objectives in terms similar to s 3 of the Protected Disclosures Act 1995 (NSW)

10

The title of the Queensland Act ('whistleblower protection') followed United States

precedent almost by default, even though the approach taken was different to that

taken in the United States, and EARC (1991: 14) had determined it was 'preferable

not to provide in legislation' a definition of the term whistleblower.

The research showed a positive relationship between levels of knowledge of, and

confidence in, relevant legislation within public sector agencies, and organisational

attitudes towards whistleblowing (and in some cases, whistleblowing behaviour)

(Roberts 2008: 236-245). These results indicate the communicative importance of

both the existence of the legislation, and how it is titled and presented.

The case study research collected anecdotal evidence confirming that the legislation's

current title works against its reputation and implementation in three ways:

•

While public officials who make public interest disclosures are indeed

'whistleblowers', most do not self-identify, nor wish to self-identify as such.

This is for a range of positive reasons, including impressions (right or wrong)

that to be labeled a whistleblower is to be singled out for retribution. One

participant described the term as having 'extremely negative connotations':

… the term alone will surely negate much of the work done to change the

culture [of organisations]. It would hardly encourage me to come forward

(despite support and assistance being available), if I knew that despite this I

was still going to be labelled a ‘whistle blower’. … Not to put too fine a

point on it but it’s a bit like why parents don’t name their babies ‘Adolph’

anymore (see Brown 2006: 6).

This is believed to be a major reason for under-reporting by agencies of the

number of public interest disclosures they deal with, as well as the continued

unwillingness of many risk-averse employees from coming forward with

information about wrongdoing (see Brown et al 2008: 265).

•

At the same time, for those public officials who do seek to self-identify as a

'whistleblower', the title of the Act fails to communicate that the legislation

extends to a particular range of reported wrongdoing ('public interest

disclosures') and not any or all wrongdoing types in respect of which public

officials may seek protection (e.g. individual grievances); and

•

The title 'whistleblower protection' can give the false impression that anyone

self-identifying as a whistleblower is automatically protected against all

possible adverse outcomes that might befall them, when this is correctly not

the case – contributing to both poor respect for and implementation of the Act

among managers, and criticism by persons whose expectations are not met.

A preferable title is Public Interest Disclosure Act, given that this is what the Act

actually deals with and focuses upon, and it is a title which circumvents the above

problems. This title is in use in the ACT, Tasmania, Western Australia, the Northern

Territory and the United Kingdom, and is proposed for the Commonwealth.

Recommendation 2. That the Act be retitled the Public Interest Disclosure Act.

Whistleblowing Legislation in Queensland: The Agenda for Reform 11

2. Subject matter of disclosure Legislation should specify the topics, or types of proscribed wrongdoing, about

which a public interest disclosure can be made. The topics should cover all

significant wrongdoing or inaction within government that is contrary to the public

interest. The topics should include:

an alleged crime or breach of the law

official corruption, including abuse of power, breach of trust, and conflict of

interest

official misconduct, and

defective administration, including:

negligence or incompetence

improper financial management that constitutes a significant waste of

public money or time, and

any failure to perform a duty that could result in injury to the public, such

as an unacceptable risk to public health, public safety or the environment.

No major reform

needed

Reform

needed

Reform

imperative

Under ss 15-19, the Act is triggered by any disclosure by a public official of

suspected:

•

•

•

•

•

official misconduct, as defined by the Crime & Misconduct Act 2001;

maladministration that adversely affects anybody’s interests in a substantial

and specific way;

negligent or improper management directly or indirectly resulting, or likely to

result, in a substantial waste of public funds (provided not based on a mere

disagreement over policy that may properly be adopted about amounts,

purposes and priorities of expenditure);

a substantial and specific danger to public health or safety or to the

environment; or

a substantial and specific danger to the health or safety of a person with a

disability.

This range of wrongdoing types is comprehensive and, in legislative terms, currently

represents national and international best practice.

12

3. Person making disclosure A disclosure should qualify as a ‘public interest disclosure’ if either of two tests is

satisfied:

(a)

the person making the disclosure holds an honest and reasonable belief that

the disclosure shows proscribed wrongdoing (the subjective test); or

(b)

the disclosure does show, or tends to show, proscribed wrongdoing,

irrespective of the person’s belief (the objective test).

The motivation or intention of the person making the disclosure should not be

relevant. Nor should a person be required to use a special form or declare that it is a

public interest disclosure.

No major reform

needed

Reform

needed

Reform

imperative

Range of persons who may make a public interest disclosure To properly serve the integrity and accountability of the public sector, whistleblower

protections should be available to all categories of government 'insider' (or former

insiders). The entire reason for creating tailored regimes to ensure proper handling

and management of disclosures by such persons, is that their internal position in the

public sector may:

(a) give them access to privileged information regarding wrongdoing, which

should be disclosed; but also

(b) place them in a position of particular vulnerability to reprisals or

repercussions, especially relating to their career, employment and basic

livelihood, the fear of which also acts as a special barrier to disclosure.

The research has confirmed that public sector whistleblowing protections should be

available to current or former:

• Public officials, including permanent and contract staff;

• Public contractors (in respect of their contracts or the public agency with

which they contract);

• Employees of public contractors (in respect of the delivery of publicly-funded

services by their employer, or the public agency with which their employer

contracts);

• Volunteers who are de facto unpaid officials or employees; and

• Anonymous persons who can reasonably be suspected to belong, or who are

later identified as belonging, to one of these categories.

The Queensland Act provides current best practice in its definition of ‘public

officer’, which includes anyone employed in or by State government, including

legislators, judicial officers, and officers of government-owned corporations.

Section 27(1) of the Act also already provides that a public interest disclosure may

be made to an appropriate entity 'in any way, including anonymously'.

Whistleblowing Legislation in Queensland: The Agenda for Reform 13

However the Act has fallen behind best practice in relation to other categories of

public sector whistleblower. This may be because EARC (1991) originally

recommended that disclosures by any person (including non-whistleblowers) should

trigger the Act, as will be discussed in Part III. Fortunately, this approach was not

proceeded with, but in the process, other categories of whistleblower were not

captured in respect of the full range of wrongdoing reportable under the Act.

An example of better practice can be found in Tasmania, where s 6(2) of the Public

Interest Disclosure Act 2002 (Tas) provides that 'a contractor' may disclose improper

conduct by 'a public body with which the contractor has entered into a contract', with

'contractor' defined to mean 'a person who at any time has entered into a contract

with a public body for the supply of goods or services to, or on behalf of, the public

body'. The Tasmanian Act also provides that a contractor may make a disclosure

after they cease 'to hold or be a party to a contract with the public body' (s.25(2)).

At a Commonwealth level, the House of Representatives Standing Committee (2009:

55) has also recommended that new legislation include a 'deeming' provision by

which persons who are insiders to government and at equivalent risk of reprisal may

be deemed to be 'public officials' for the purposes of the Act.

Recommendation 3. That Part 3 of the Act be amended to provide that a public

interest disclosure on any matter may be made by:

• a public contractor (in respect of their contracts or the public agency with

which they contract), an employee of a public contractor (in respect of the

delivery of publicly-funded services by the contractor, or the public agency

with which their employer contracts), or a volunteer who is de facto an

unpaid public official or employee of a public contractor; or

• a public officer, public contractor, employee of a public contractor, or

public volunteer who has ceased to work in that capacity or hold that

contract.

Further, that if the Commonwealth proceeds with a 'deeming' provision for who

may make a public interest disclosure, consideration be given to including such a

provision in the Queensland Act.

Tests for disclosure Section 14(2) of the Act provides that a public interest disclosure will trigger the Act

if the person making it 'honestly believes on reasonable grounds that the person has

information that tends to show the conduct or danger'.

This provision has been shown to provide an appropriate test for when the Act's

requirements should apply. It is superior to a purely objective test, under which the

information disclosed must actually show or tend to show a proscribed form of

wrongdoing (required in NSW, South Australia and Western Australia: see Brown

2006: 22).

However, the best possible approach would be for the legislation to provide that the

Act is triggered either when a whistleblower honestly believes on reasonable grounds

that the information tends to show wrongdoing, or when a whistleblower provides

information which tends to show wrongdoing, even if they have no belief as to that

fact or as to what type of wrongdoing might be shown.

14

This approach would guard against the possibility of protection failing (e.g. in an

action for defamation, or in defense of an action for compensation) because it was

shown that the whistleblower did not hold the required level of understanding about

the information that they were supplying, at the time they supplied it, for it to be a

public interest disclosure.

Recommendation 4. That s 14(2) of the Act be amended to provide that a

disclosure will trigger the Act, either (a) if the person making it honestly believes

on reasonable grounds that the information tends to show the conduct or danger,

or (b) if the information does tend to show relevant conduct or danger, irrespective

of what the person believed it to show at the time they made the disclosure.

4. Receipt of disclosure Legislation should allow a public interest disclosure to be made to a variety of

different people or agencies, including:

the immediate or any higher supervisor of the person making the disclosure

the chief executive officer of the agency

any designated unit or person in an agency

any dedicated hotline, including external hotlines contracted by an agency, or

any external agency with jurisdiction over the matter (eg, ombudsman,

corruption commission, auditor-general, or public sector standards

commissioner).

No major reform

needed

Reform

needed

Reform

imperative

Sections 26(1) and 27(3) of the Act provide current best legislative practice in the

range of avenues by which a public interest disclosure may be made, to appropriate

entities within government. These were last extended in 2006, when the Queensland

Parliament legislated to allow public interest disclosures to be made to Members of

the Legislative Assembly, in response to the Bundaberg Hospital Commission of

Inquiry (Davies 2005).

Most importantly, the avenues include the requirement that the responsibility to

recognise and receive disclosures needs to be embedded in the duties of all public

sector managers (see Brown 2008: 293ff). At the same time, it is explicit that other

internal and external disclosure avenues are also available.

The issue of when a public interest disclosure should also be able to be made outside

internal or external government channels, for example to the media, is dealt with

below under principle 10.

Whistleblowing Legislation in Queensland: The Agenda for Reform 15

5. Recording and reporting All public interest disclosures to an organisation should be formally recorded,

noting the time of receipt, general subject matter, and how the disclosure was

handled. Recording systems, including required levels of detail, will vary

according to agencies’ circumstances, but should be consistent with minimum

standards across the public sector (see principle 7).

No major reform

needed

Reform

needed

Reform

imperative

Sections 29 and 30 of the Act require all public agencies to keep records of public

interest disclosures received, and action taken, with basic information on numbers

and outcomes of investigations to be published in their annual report.

However, the research revealed that most agencies currently lack sufficiently

comprehensive systems for recording and tracking employee reports of wrongdoing

– especially at junior and middle management levels, where the bulk of disclosures

are made in the first instance (Brown 2008: 304).

Some agencies still have no such systems, despite these being a basic prerequisite to

effective monitoring of how many public interest disclosures are being made, what

investigation or other action is being taken, and how those involved in the

disclosures are being managed, at an agency and a whole-of-government level. In

particular, they are vital to the early identification of the risks of reprisals, conflicts

or other detrimental outcomes, at a stage when such outcomes might still be able to

be averted or minimized.

The frequent lack of effective agency-level systems for implementing the legislation,

calls for clearer and more detailed requirements to be placed in agency-level

procedures, and for these to be supported and enforced by more active central

oversight and coordination. These are dealt with below under principles 7 and 11.

6. Acting on a disclosure An agency receiving a disclosure should be obliged:

to assess that disclosure and take prompt and appropriate action, which may

include investigating the disclosure or referring it to an external agency

to the extent practicable and reasonable, to keep the person who made the

disclosure informed of action proposed to be taken, the progress of any action,

and the outcomes of any action, and

to include in its annual report a summary of the numbers of public interest

disclosures received, and the action taken.

No major reform

needed

Reform

needed

Reform

imperative

16

While the third of these requirements is met by the current Queensland Act, the first

two are not.

Sub-section 30(2) of the Act requires agencies to report on how many disclosures

were verified each year, which tends to presume some investigation. However the

Act otherwise imposes no clear guidance or responsibilities on agencies as to how

they should deal with disclosures, nor whether or how they must keep the parties to

the investigation (including the whistleblower) informed.

The research demonstrated the absolute importance of public employees' confidence

that a disclosure will be acted upon, to their decision to blow the whistle (Brown

2008: 53-82). Originally, EARC (1991: 125-133) also sensibly proposed basic duties

to investigate, but these were omitted from the legislation.

Section 32 of the Act requires agencies to provide reasonable information to a person

who makes a public interest disclosure, about the response to and outcomes of the

disclosure – but only when asked.

The research demonstrated that this is not a sufficient approach (Brown 2008: 109136). The whistleblowers in most need of information about what is occurring, may

not be those most likely to ask; and whistleblowers may not necessarily know when

to ask, until after they begin experiencing problems. An active strategy for managing

the expectations, fears and risks that surround a whistleblower, including a proactive

approach to keeping them reasonably informed of progress and outcomes, is

instrumental to the prevention and containment of a range of real and/or perceived

difficulties in whistleblowing outcomes.

There is no single model of legislative best practice for duties relating to

investigations (Brown 2006: 28-32). Legislation in other Australian jurisdictions

varies between imposing scant duties, on the assumption that investigation will occur

under other Acts, to detailed provisions which are sometimes imperfect and conflict

with other Acts.

Taking this experience together, in light of the research, new legislative best practice

would be to provide:

• A general requirement that all public interest disclosures must be assessed and,

where appropriate, investigated;

• Appropriate discretions for when an agency may assess that a public interest

disclosure does not require investigation, namely when:

- The substance of the disclosure has already been investigated or dealt with

by another appropriate process;

- The substance of the disclosure should be dealt with by another process;

- The disclosure is old, or age renders it incapable of investigation;

- The disclosure is otherwise incapable of investigation;

- The disclosure is manifestly too trivial to warrant investigation; or

- An external integrity agency with jurisdiction over the matter agrees, or

determines, that investigation is not warranted in all the circumstances.

•

A procedure for automatic internal and/or external review of agency-level

assessments that a public interest disclosure does not require investigation;

Whistleblowing Legislation in Queensland: The Agenda for Reform •

•

17

General requirements that a person who makes a disclosure (if known) must be

given reasonable information about the action proposed to be taken in

response, the progress of the action, and the results of the action; and may also

make reasonable requests for this information; and

A proviso that in the event of inconsistency between these requirements, and

more detailed requirements relating to the investigation of the matter under

other legislation, then to the extent of the inconsistency, the requirements in

the other legislation will apply.

Recommendation 5. That a new Part 5 be inserted in the Act (also replacing the

current ss 30-32) providing minimum duties and standards for the assessment and

investigation of disclosures under the Act, for the provision of information about

action taken to persons who make disclosures, and for public and parliamentary

reporting on the Act's operation.

7. Oversight agency One of the external agencies with responsibility for public interest disclosures

should be designated as the oversight agency for the administration of the

legislation. The responsibilities of the oversight agency should include:

being notified by agencies of all disclosures, and recording those disclosures

and how they were dealt with and resolved

having the option to decide, upon being notified of a disclosure, to provide

advice or direction to an agency on how the disclosure should be handled, to

manage the investigation of the disclosure by the agency, or to take over the

investigation of the disclosure

providing advice or direction to agencies on the steps that should be taken to

protect people who have made disclosures, or to provide remedial action for a

person who has suffered detriment as a result of making a disclosure

promoting the objects of the legislation, both within government and publicly,

and conducting training and public education

publishing model procedures for the administration of the legislation, with

which agencies’ internal procedures must be consistent; and

conducting a public review at least once every five years of the operation of the

legislation.

No major reform

needed

Reform

needed

Reform

imperative

As noted in the Green Paper (p.25), the Act created a scheme which sought to make

'each public sector agency responsible for receiving public interest disclosures about

the conduct of its officers, managing the disclosure process and taking steps to

protect its officers from reprisals.' The alternative, as seen at the time, was a

18

centralized system with one agency responsible for protecting whistleblowers in

Queensland (see EARC 1991: 122-125, 149-154, 184-188).

This was a false dichotomy. In hindsight, it would always have been more logical to

pursue a more effective path between these two extremes.

While rejecting the idea that one agency should act as the point of receipt, referral

and coordination for all disclosures (EARC 1991: 122-125), EARC did recommend

that implementation of the Act should be ensured by having the Criminal Justice

Commission (CJC, now CMC) act as a general oversight agency. This was proposed

to be achieved by:

•

Requiring all agencies to develop relatively detailed procedures for the

handling of public interest disclosures, including employee protection;

•

Empowering the CJC to receive, refer and where necessary, investigate any

type of public interest disclosure (not limited to official misconduct);

•

Empowering the CJC to oversight the existence and quality of agency

whistleblowing procedures, including the power to give standing or specific

directions to agencies regarding modification of their procedures;

•

Requiring the CJC to establish a whistleblowers counseling unit to provide

'counselling and assistance' to whistleblowers and potential whistleblowers

regarding the operation of the Act (EARC 1991: A11-12, A16-17).

However, not even these minimal requirements for coordination and standard-setting

were incorporated in the Act.

The CJC did establish a small whistleblowing support unit, without statutory

authority or roles, which was wound up by 1999. One apparent reason was the unit's

inability to find out about, let alone intervene in, whistleblowing cases being handled

by agencies at the stages when intervention might have been more productive.

Instead, apart from the requirement for agencies to annually report upon disclosures

received under the Act (above), the only provisions for ensuring the implementation

of the legislative scheme were:

• The requirement under s 44 that every agency 'must establish reasonable

procedures to protect its officers from reprisals that are, or may be, taken

against them by the entity or other officers of the entity'; and

• The requirement under s 31 that the responsible Minister (the Premier) 'must

prepare for each financial year an annual report to the Legislative Assembly

on the administration of this Act'.

These requirements can now be seen, in light of the research, to have substantially

failed. In addition to the research outcomes noted in Part I, the frequent absence, and

comparatively low quality of basic whistleblowing procedures and systems in many

Queensland Government agencies is further discussed under principle 11.

Over the 15 years of the Act's operation, rarely, if ever, has the Premier or the

Queensland Department of Premier and Cabinet compiled and published any

comprehensive annual report on the administration of the Act, whether as a stand

alone report or as part of the annual reporting obligations of the Department or its

agencies. In 2006, the Office of the Public Service Commissioner conducted an

internal-to-government review of the Act, examining three years of data on its

Whistleblowing Legislation in Queensland: The Agenda for Reform 19

performance, but declining to recommend significant reform (OPSC 2006). The

Whistling While They Work project team was not consulted by that review.

The question is what now should be done to put in place an effective framework for

oversighting the implementation of the Act.

An existing outcome of the research is the recommendation that all jurisdictions put

in place a dedicated oversight agency or unit for the coordination of responses to

employee-reported wrongdoing. The recommended statutory roles of the oversight

agency – which may be an existing agency – are set out under principle 7 above, and

further discussed in the first report (Brown et al 2008: 269-271; 310-311).

The House of Representatives Standing Committee (2009: 126-8, 132-7) has already

accepted this recommendation in respect of Commonwealth legislation,

recommending that these roles be conferred on the Commonwealth Ombudsman.

In Victoria, these roles are fulfilled under statutory mandate by Ombudsman

Victoria. In Western Australia, they are fulfilled by the Office of the Public Sector

Standards Commissioner. In the Northern Territory, they are fulfilled by a new

Commissioner for Public Interest Disclosures, located in the office of the

Information Commissioner.

In Queensland, in light of proven inadequacies in implementation of the Act by

Queensland Health as well as other general difficulties in its operation, the

Bundaberg Hospital Commission of Inquiry recommended that:

…. the Queensland Ombudsman be given an oversight role with respect to all public

interest disclosures save those involving official misconduct. I recommend a system

similar to that involving Official Misconduct where all public interest disclosures must

be referred to the Ombudsman who may then either investigate the disclosure itself, or

refer it back to the relevant department for investigation, subject to monitoring by the

Ombudsman (Davies 2005: 472, Rec 6.510).

This recommendation was supported by the Queensland Ombudsman and the Crime

& Misconduct Commission. However, the Queensland Government declined to

implement this recommendation, based on advice from the Queensland Health

System Review (the Forster Review) and Office of the Public Service Commissioner

(OPSC 2006: 12-21).

In my respectful opinion, the advice of the OPSC – on which the Whistling While

They Work project team was not consulted at the time, and with which the

Ombudsman continued to disagree – was neither internally consistent nor persuasive.

It was also prepared in consciousness that the results of the Whistling While They

Work project were not yet available (OPSC 2006: 2). The Queensland Government

should consider that advice to have now been superseded.

The choice of which agency should undertake these roles is one for Government.

The main considerations are that the roles include:

• Routine supervision of and assistance to agencies in respect of their policies,

practices and procedures;

• An ability to oversight the numbers and quality of investigations being

conducted by agencies (in close coordination with any other agencies

oversighting the same or similar investigations, including the CMC if the

oversight agency is not the CMC);

20

•

•

•

An ability to take over or conduct investigations where necessary, or refer

investigations to more appropriate bodies;

An ability to develop specialist expertise in reprisal risk assessment,

workplace strategies for preventing poor whistleblowing outcomes, and the

investigation and remediation of reprisals or poor outcomes; and

An ability to coordinate the operations of the oversight agency/unit with the

many agencies involved in implementation of aspects of the Act.

No agency should be tasked with these functions without legislative authority, and

appropriate financial resources. However the research strongly suggests that no

government can reasonably expect to achieve substantial improvement in the

implementation of the Act unless it tasks an appropriate agency with these functions.

Recommendation 6. That a new Part be inserted in the Act (also replacing the

current s 31) establishing a new framework for oversight and coordination of the

implementation of the Act, including a designated agency or unit with a

clearinghouse and quality assurance role for individual investigations, and

responsibility to promote, support and require best practice agency whistleblowing

programs.

8. Confidentiality Disclosures should be received and investigated in private, so as to safeguard the

identity of a person making a disclosure to the maximum extent possible within the

agency’s control. Avenues should be available for disclosures to be made

confidentially, and where practical, individual disclosures should be dealt with in

ways that do not disclose the identity of the person making the disclosure, and

preferably even that a disclosure has in fact been made. This principle is subject to

the need to disclose a person’s identity to other parties – for example, where this is

absolutely necessary to facilitate the effective investigation of a disclosure, provide

procedural fairness, protect a person who has made a disclosure, or make a public

report on how a disclosure was dealt with.

No major reform

needed

Reform

needed

Reform

imperative

Section 55 of the Act requires confidentiality to be maintained in the administration

of the Act, with appropriate qualified exceptions to deal with the need for

investigations and for the provision of natural justice.

However, best practice requires that the Act also provide flexibility in the constraints

that absolute confidentiality requires, in circumstances where it is necessary to reveal

information or even identify a person who made a public interest disclosure – with

their informed consent – in order to better protect and support them.

Whistleblowing Legislation in Queensland: The Agenda for Reform 21

The importance of this flexibility was significantly reinforced by the research

findings, that it is frequently not possible to maintain confidentiality in respect of a

public interest disclosure in practice – turning a strong statutory requirement into an

inflexible hindrance to the effective management of a whistleblowing situation, in

many situations (see Brown 2008: 149; Roberts et al 2009: 73-76).

Unlike the legislation in force in NSW, Western Australia and the Northern Territory

(Brown 2006: 47-48), the Queensland Act does not contain a provision which

enables the identity of a person to be revealed with their consent or in other

circumstances where there is a reasonable excuse why confidentiality should not be

maintained. Queensland Government agencies have reported these limitations as

representing operational barriers to the implementation of the Act.

Recommendation 7. That sub-section 55(3) of the Act be amended to provide that

a person may make a record of confidential information or disclose it to someone

else, for purposes including the protection of any person under the Act, including a

person who has made a public interest disclosure – provided that information

which identifies or could tend to identify a person who has made a public interest

disclosure may only be disclosed with the prior, informed consent of that person,

or, if consent is impossible to obtain, where the interests of that person are not

harmed and there is reasonable excuse to do so.

9. Protection of person making disclosure A person who has made a disclosure to which the legislation applies should be

protected against criminal or civil liability, or other detriment, for making the

disclosure. For example, the person:

should not be liable to prosecution for breach of a statutory secrecy provision

should not incur civil liability for, for example, defamation or breach of

confidence

should not be subject to discipline or other workplace sanction, such as

reduction in salary or position, or termination of employment, and

should be entitled to legal redress if they suffer detriment as a result of making

the disclosure.

No major reform

needed

Reform

needed

Reform

imperative

Sections 39-43 of the Act extend comprehensive legal protections to public sector

whistleblowers under the Act, in line with its basic objectives.

Several features of these provisions continue to represent best legislative practice.

However they are currently defective in two respects relating to the availability of

legal redress if a whistleblower suffers detriment as a result of a disclosure.

22

The first defect relates to the legal and procedural barriers that stand in the way of

any person effectively pursuing an entitlement to damages for detriment caused,

under s 43. These issues are addressed below under principle 12.

The second defect is that only a public officer may be prosecuted for the criminal

offence of taking a reprisal against a person because, or in the belief that, anybody

has made, or may make, a public interest disclosure (s 42). While the Act and the

Criminal Code contemplate that a public officer may still be prosecuted even if

others who are not public officers are also involved, the offence is not prosecutable

against persons who are not public officers, acting alone.

The research suggests that much over-reliance has been placed on the usefulness of

the criminal offence of reprisal, as a means of achieving legal redress for the

detriment suffered by most whistleblowers, given that the nature of that detriment is

only rarely such that would make a prosecution appropriate (Brown 2008: 127-131).

Nevertheless, as long as such an offence is retained for its symbolic and deterrent

effects, it should be comprehensive and practical. The original proposal of EARC

(1991: A19) was that any person who takes a reprisal should be criminally liable.