Dividing the inseparable

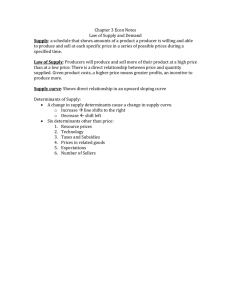

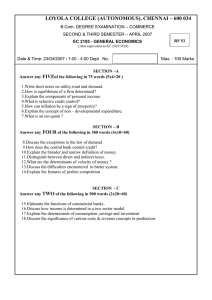

advertisement