Visual Ethics: Ethical Issues in Visual Research

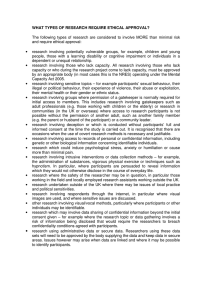

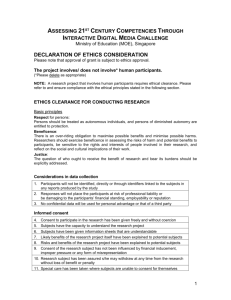

advertisement