Liquid Hazard - Global Risk Consultants

advertisement

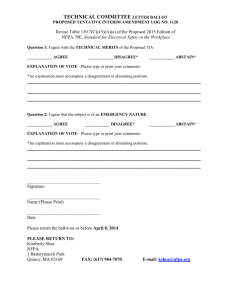

» PERSPECTIVES VIEWPOINTS ON FIRE + LIFE SAFETY Liquid Hazard A new advocacy effort seeks regulatory consistency around the manufacture, transport, and storage of flammable and combustible liquids INTERVIEW CONDUCTED AND EDITED BY JESSE ROMAN, NFPA JOURNAL STAFF WRITER FOR ANYONE STORING AND transporting flammable and combustible liquids, the stakes could not be higher, according to David Nugent, who has worked in the field of industrial fire protection for more than 30 years. Fires that occur with these liquid chemicals can result in injuries and fatalities to building occupants, the surrounding population, and emergency responders. These fires can also cause significant damage to the environment— destroying wildlife, contaminating drinking water, and sending toxic chemicals into the air. Given the potential dangers, you might expect the safety regulations on how these products are shipped and stored 22 NFPA JOURNAL MAY/JUNE 2015 to be widely adopted, and you’d be right—to a degree. More than 30 states have adopted NFPA 30, Flammable and Combustible Liquids Code, which outlines the hazards, and prescribes in detail the protection required to prevent and mitigate those risks, said Nugent, who has been on the NFPA 30 technical committee for more than 10 years. But, according to Nugent and a newly formed advocacy group called the Industrial Packaging Safety Alliance, there’s one big problem. The two biggest federal regulators of these chemicals, the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), “are lagging way behind” many of the safety Photographs: Shutterstock measures prescribed in NFPA 30, Nugent said. The result is a regulatory disconnect that can cause confusion for companies that manufacture, ship, and store these products, which as a result increases the risk of an accident, he said. DOT regulates the transportation of flammable and combustible liquids, but its codes do not consider fire protection or how well containers will perform in a fire situation. As a result, compliant DOT containers, perfectly legal on the road, might not be compliant with the majority of state and local fire codes—based on NFPA 30—when they reach their destination, Nugent said. Meanwhile, OSHA regulations, which are based on NFPA 30, aren’t up to par either, according to Nugent. That’s because they are based on the 1969 edition of NFPA 30, much of which is silent on many of the important information in the latest 2015 edition. Achieving regulatory clarity and consistency is the goal of the Industrial Packaging Safety Alliance, also known as PackSafe. The effort seeks support from a coalition of stakeholders including manufacturers and users of packaging material, risk managers, insurers, and code officials. PackSafe announced its formation on April 14 with the release of “Transportation and Storage of Containerized Flammable and Combustible Liquids: The Disconnect Between U.S. Federal Regulations, and State and Local Fire Codes,” a white paper written by Nugent. Nugent, who currently works as a senior consultant for Global Risk Consultants, spoke with NFPA Journal about the aims of PackSafe and how disparities in federal, state, and local regulations can lead to unsafe conditions. What kinds of chemicals are we talking about and how do you classify which ones pose the most risk? There are hundreds of pure and blended materials categorized as flammable and combustible liquids out there. When classifying these materials, we’re looking at the physical properties of a liquid and how easily it ignites. NFPA 30 ranks these liquids into six classes based on the flashpoint, but there are other properties to consider, such as the heat release rate. Each chemical has a unique heat of combustion. A material like gasoline, for instance, has a much higher heat of combustion than an alcohol blend like whiskey, so if whiskey is ignited, it burns with a much lower heat release rate than gasoline. Another thing to consider is reactivity. Some of these liquids are chemically reactive—not only will they burn, but some will self react when they get above a certain temperature. These substances can be packaged in containers in an array of sizes and types, based on customer demand. Containers are made from glass, steel, plastic, fiberboard, or various combinations integrated into composites. nfpa.org/ liquid_hazard Read “Transportation and Storage of Containerized Flammable and Combustible Liquids: The Disconnect Between U.S. Federal Regulations, and State and Local Fire Codes,” a white paper written for PackSafe by David Nugent. Where are they stored? There are three main categories: Production plants or factories that either use or manufacture materials; warehouses or standalone distribution centers; and retail settings like big-box stores. In terms of size, you could have a facility where these materials are stored in a small room with several hundred gallons, or it could be a warehouse or large distribution center with millions of gallons. Is there an incident that illustrates the environmental damage a fire in one of these facilities can cause? In 1986, a Sandoz agrochemical storehouse in Switzerland caught fire. The local fire department took water from the Rhine River, which was just a few hundred feet away, and discharged it on the fire. Where do you think all the water went? It drained right back into the river, carrying tons of chemicals with it. The disaster killed the fish for nearly the entire length of the river, from Switzerland all the way to the river’s mouth in The Netherlands, on the North Sea. If you want to see the environmental impact these fires can have, that’s your poster child. What federal agencies and regulations oversee the industry in the U.S.? DOT uses Title 49 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), which has a series of provisions addressing the transportation of hazardous MAY/JUNE 2015 NFPA JOURNAL 23 » PERSPECTIVES materials, including flammable and combustible liquids. This regulation is based on United Nations’ recommendations. OSHA uses 29 CFR 1910.106, which applies to the handling, storing, and use of flammable and combustible liquids. The OSHA code is based on the 1969 version of NFPA 30 and certain interpretive letters. That code is 46 years old. Neither the DOT or OSHA regulations sufficiently address fire risks associated with flammable or combustible liquids. Why hasn’t OSHA updated to a more recent version of NFPA 30? I’ve been involved with NFPA 30 since the late 1980s and I have never been given a good reason why OSHA continues to use the 1969 version of NFPA 30. It’s confounding. How has NFPA 30 changed since 1969? For starters, there have been 15 revisions to NFPA 30 since 1969. The most significant change occurred in the 1996 edition, a result of a 1987 fire at a Sherwin-Williams paint warehouse in Dayton, Ohio. The fire spread very quickly because the building contained 1.5 million gallons of unprotected flammable liquid. The building did have water-based sprinklers, but they were totally inadequate for the stored commodity. That fire was a wake-up call for a lot of people, and it made us realize the shortcomings of NFPA 30—back then, the code wasn’t as sophisticated as it is today. The tables that specify container size and class of liquid allowed, as well as sprinkler system design criteria—none of it was based on actual fire tests. Also, the information was located in the appendix of the code, which meant it was not enforceable. Following the Sherwin-Williams fire, NFPA restructured the NFPA 30 technical committee, and a number of large fire test programs took place, many of which were organized by the Fire Protection Research Foundation. As a result, a whole new series of protection tables evolved and were moved into the body of the code. The code became so much more meaningful, because the protection schemes were based on actual fire tests that mimicked real situations. 24 NFPA JOURNAL MAY/JUNE 2015 I imagine there have been a lot of advancements in technology and research since then, too. There have been many changes to both container types and how they perform in fires, and to sprinkler system designs and technology. The 1969 version of NFPA 30 had little to no information on electrostatic ignition risk. NFPA now has an entire standard, NFPA 77, Recommended Practice on Static Electricity, that addresses it. OSHA is totally silent on all of these changes. The 2015 edition of NFPA 30 has specific prescriptive requirements that address all of these changes and issues. What happens in a state or local jurisdiction that has adopted a recent version of NFPA 30? Does OSHA take precedence, or do local laws? If you ask that question of OSHA, “Which path should we follow?,” they are OK with people following the latest version of NFPA 30, or the version adopted at the local or state level. So what’s the problem? Doesn’t that sufficiently cover it? Problems arise when people wrongfully assume that something that is compliant with DOT or OSHA is also compliant with local and state codes. That can be confusing and can lead to increased fire risk. If people are not informed on the range of applicable codes at the federal and local levels, they might be using a storage strategy that is inadequate. They could be in violation of local codes, which is a big problem in and of itself. What exactly is PackSafe and when was the effort launched? It’s an alliance of stakeholders attempting to address this disconnect between federal regulations and local and state codes and make industrial packaging safer for workers and the public. We are advocating regulatory clarity and consistency by engaging the legislative and regulatory bodies out there that write these federal regulations. The effort really began about 14 months ago and it’s been building ever since. A lot of time was spent defining the problem, coming up with a strategy and plan, and explaining the plan to all the stakeholders. Now we’re focused on executing the plan. What’s the plan and where are you now? The next step is to submit a formal letter to OSHA asking it to exercise reasonable diligence and reply to a simple question: How can PackSafe assist OSHA in reviewing and updating OSHA regulations to incorporate the 2015 version of NFPA 30? Our vision is for OSHA to incorporate the 2015 edition of NFPA 30 by reference. There is also a parallel educational process going on. I wrote a white paper that is being widely distributed, including to government officials and members of the Congressional Fire Services Caucus. who work in these various occupancies, educating people on regulation compliance is a pretty significant effort, and this is just one of many facets to regulatory compliance. If you can make it simpler and more effective, it makes everyone’s job easier and leads to a safer workplace. Is this lag in federal code adoption unique, or part of a bigger problem? I’m aware of other issues with outdated codes, but as far as PackSafe is concerned, we are just focused on the issues I’m outlining here. We’re not here to right all the wrongs of federal regulation—we could spend lot of time on that I’m sure. But this is such a difficult thing to change, we just want to focus on this issue and get OSHA to adopt NFPA 30 and hopefully have an influence on DOT so it does not continue to ignore the fire risk, like it is currently doing. How widely is PackSafe supported among other stakeholders in the industry? These people all get it—the more people you talk to and explain this to, you get a lot of “wows.” Almost everyone who hears about this thinks it’s a great idea and wants to support it in some way. Everyone in the industry confronts these issues; this is their day to day, and it’s a real headache. Think about it: if you have employees MAY/JUNE 2015 NFPA JOURNAL 25