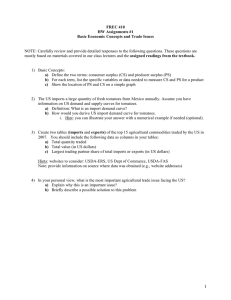

European Community Protection against Manufactured Imports from

advertisement