International Journal of Electronics Parasitic resistance current

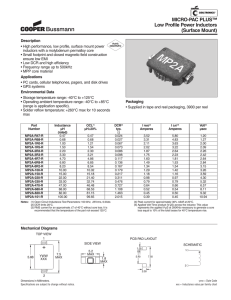

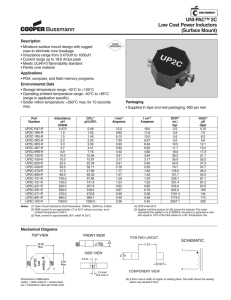

advertisement

This article was downloaded by: [University of Central Florida] On: 26 August 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 787036435] Publisher Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 3741 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK International Journal of Electronics Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713599654 Parasitic resistance current sensing topology for coupled inductors Shangyang Xiaoa; Weihong Qiua; Jun Liua; Thomas X. Wub; Issa Batarsehb a Intersil Corporation, Milpitas, USA b School of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL, USA To cite this Article Xiao, Shangyang , Qiu, Weihong , Liu, Jun , Wu, Thomas X. and Batarseh, Issa(2009) 'Parasitic resistance current sensing topology for coupled inductors', International Journal of Electronics, 96: 1, 51 — 61 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/00207210802492336 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00207210802492336 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. International Journal of Electronics Vol. 96, No. 1, January 2009, 51–61 Parasitic resistance current sensing topology for coupled inductors Shangyang Xiaoa*, Weihong Qiua, Jun Liua, Thomas X. Wub and Issa Batarsehb a Intersil Corporation, Milpitas, USA; bSchool of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL, USA Downloaded By: [University of Central Florida] At: 03:54 26 August 2010 (Received 10 July 2008; final version received 13 September 2008) Traditional current sensing topology based on inductor equivalent series resistance fails to extract phase currents for coupled inductors due to the presence of the magnetising inductance. This article proposes a new direct-current resistance current sensing topology for coupled inductors. By implementation of a simple resistor-capacitor network, the proposed topology can preserve the coupling effect between phases. As a result, real phase inductor currents and total current can be sensed. Detailed mathematical analysis and design equations are presented in this article. Sensitivity and mismatch issues are addressed. Experimental results show that the proposed topologies are able to extract phase current as well as total current with acceptable accuracy. Keywords: power electronics; DC–DC converter; voltage regulator; coupled inductors; current sensing; inductor parasitic resistance 1. Introduction The ever-stringent transient and efficiency requirements of recent microprocessors have posed great challenges on voltage regulator (VR) design (Voltage Regulator-Down http:// www.intel.com). Coupled inductors are an emerging topology for power supplies. In recent years, multiphase VRs with coupled inductors have drawn more and more attention from both industry and academia because of their better performance than traditional discrete-inductor multiphase VRs. The work by Schultz and Sullivan (2001), Jieli et al. (2002), Ledenev et al. (2004), Herbert (2005), Xu et al. (2007), was involved in various coupled-inductor topologies and modelling in which the number of coupled phases is larger than two; whereas in the study by Pietkiewicz and Tollik (1998), Chen et al. (1999), Wong et al. (2000), Wu et al. (2006), Zhou et al. (2005), two–two coupled-inductor VRs were explored. Since the linear structure of multiphase coupled inductors is inherently asymmetrical, with coupling phase number more than two, the non-identical magnetic characteristics for different phases may lead to sub-harmonic output ripple (Wu et al. 2006). As a result, two–two coupled-inductor VR is usually preferred in industry. This article will limit the scope to discussion of two–two coupled inductors only. As technologies advance, current mode control, droop control (also referred as adaptive voltage positioning), over-current-protection, phase-current limit and other advanced power management features are becoming common industry practice. *Corresponding author. Email: sxiao@intersil.com ISSN 0020-7217 print/ISSN 1362-3060 online Ó 2009 Taylor & Francis DOI: 10.1080/00207210802492336 http://www.informaworld.com Downloaded By: [University of Central Florida] At: 03:54 26 August 2010 52 S. Xiao et al. To implement these technologies, the phase currents need to be sensed and fed back to the PWM (pulse width modulation) controller. Therefore, a proper current sensing technique is desired. Conventionally, a dedicated sense resistor is placed after each phase inductor to achieve high-accuracy current sensing. As next generation microprocessors demand more power and higher efficiency, this method becomes undesirable since it introduces significant conduction loss. Recently, the metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET) on-resistance (Rdson) current sensing has been utilised in industrial products. Unfortunately, the tolerance of MOSFET on-resistance usually falls in the 30– 40% range (Hua and Luo 2006). Poor current sensing accuracy leads to phase-to-phase current unbalance. For high-current multiphase VRs, current unbalance leads to stability and thermal issues which could be disastrous. The current-sensing schemes presented by Ma and Lee (1994), Zhou et al. (1999), Dallago et al. (2000), Forghani-zadeh and RinconMora (2002, 2005) show advantages in terms of current sensing accuracy. However, complexity limits their utilisation in VR application. 2. Limitations of conventional DCR current sensing topology In recent years, inductor parasitic-resistance current sensing (also referred as DCR current sensing) has been prevailing in the VR industry (LinFinity 1998; Walters et al. 1998; Dong et al. 2006; ISL6327), although the concept can date back to Maxwell bridge decades ago (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maxwell_bridge). The inductor parasiticresistance (DCR) current sensing method employs a resistor and a capacitor across the inductor to extract the voltage drop on the output inductor parasitic resistance. If the resistor-capacitor (RC) network components are selected such that the RC time constant matches the inductor time constant (L/DCR), the voltage across the capacitor is equal to the voltage drop across the DCR, i.e., the phase current is replicated (ISL6327). Because the tolerance of inductor copper trace can be controlled within up to 5% with current process (Hua and Luo 2006; LC1740-R30R10A), the accuracy of DCR current sensing can be significantly improved compared to the MOSFET Rdson sensing method. In addition, despite that the RC sensing network has some AC losses, the DC loss on it is almost zero. Furthermore, the overall cost of the RC network may be even cheaper than a sense resistor. Thus, as a cost-effective practice, DCR sensing is widely implemented in VR applications. However, even though DCR current sensing has been well investigated for discrete inductors, little work has been done on current sensing for coupled inductors. In most coupled-inductor applications, the traditional DCR sensing method is simply applied to coupled inductors (Dong et al. 2006; Xu et al. 2007; Wu et al. 2006). The RC network is designed based on the leakage inductance while the magnetising inductance is neglected. Since the phase currents of coupled inductors are different to those of discrete inductors due to the presence of magnetising inductance and coupling effect, the application of conventional DCR current sensing to coupled inductors is questionable (Xiao et al. 2008). Figure 1 shows a two-phase coupledinductor VR with traditional DCR current sensing topology, where VP1 and VP2 represent the phase voltages (referring to VO); R and C are the current-sensing network components for each phase. A widely utilised model (Pietkiewicz and Tollik 1998; Chen et al. 1999; Wong et al. 2000; Schultz and Sullivan 2001; Jieli et al. 2002; Ledenev, et al. 2004; Herbert 2005; Xu et al. 2007; Zhou et al. 2005; Wu et al. 2006) of coupled inductors is employed. This circuit model consists of a leakage inductance (Lk) in series with the inductor DCR for each winding, and an ideal transformer with a magnetising inductance (LM) on one of the windings. Downloaded By: [University of Central Florida] At: 03:54 26 August 2010 International Journal of Electronics Figure 1. 53 Coupled inductors with traditional DCR current sensing topology. Assuming that the coupled inductors are symmetric for the purpose of simplicity, the phase voltage VP1 is written in s-domain as: VP1 ¼ sðLk þ LM Þ iL1 sLM iL2 þ DCR iL1 ð1Þ where s is a complex argument in s-domain. Since VP1 is also the voltage across R and C, the voltage across C for phase 1 can be expressed as: VC ¼ sðLk þ LM Þ iL1 sLM iL2 þ DCR iL1 1 þ sR C ð2Þ With the RC time constant matching the inductor Lk/DCR time constant, Equation 2 is simplified to: VC ¼ DCR iL1 þ sLM ðiL1 iL2 Þ 1 þ sR C ð3Þ The first term represents the DC current across DCR whereas the second term cannot be cancelled out due to the magnetising inductance. Therefore, Equation 3 suggests that traditional DCR current sensing method cannot extract the correct phase current information. It is the superposition of the phase DC current and additional AC components. Figure 2 shows experimental results obtained from a built prototype. The top one shows the sensed phase current by traditional DCR sensing and the bottom waveform represents the real phase current. With the RC time constant matching the time constant of leakage inductance and DCR, it is found that the sensed current is distorted. Consequently, wrong phase current information is fed back to the controller which leads Downloaded By: [University of Central Florida] At: 03:54 26 August 2010 54 S. Xiao et al. Figure 2. Experimental current waveforms for coupled inductors with traditional DCR current sensing (X-axis: 5 mV/div for channel 1 and channel 2; Y-axis: 2 mS/div). to improper phase over-current-protection as well as inferior current and voltage regulation in return. Motivated by the demand of a cost-effective current sensing technique for coupled inductors, a new DCR current-sensing topology is proposed in this article. By implementation of a simple RC network, the phase currents as well as total current can be extracted. The design equations for the RC sensing network are derived by stepby-step mathematical analysis. These equations are given in terms of leakage inductance and magnetising inductance since these coefficients are usually provided in the coupled-inductor datasheets by vendors (LC1740-R30R10A). Sensitivity and mismatch issues are addressed. A prototype has been built to verify the theoretical results. 3. Proposed inductor parasitic resistance current sensing topology Figure 3 shows the proposed parasitic resistance current sensing topology for two–two coupled inductors. This topology consists of a capacitor C and two resistors for each phase, where R1, R2 are for phase one and R3, R4 are for phase two, respectively. For the purpose of simplicity, two phases can be assumed to be symmetric. Then, R1 is equal to R4 and R2 is equal to R3. VP1 and VP2 are denoted as phase voltages (referring to VO). Under some circumstances, it is necessary to use a resistor divider to scale down the sensed current or to compensate the temperature variation of DCR. This can be accomplished by placing a thermal resistor RC in parallel with the capacitor C for each phase. By properly sizing the resistor and capacitor values in the topology, the phase current can be represented by the voltage across C, i.e. VC. VC is then sent to a current amplifier inside the PWM controller for current and voltage regulation as shown in Figure 1. 55 Downloaded By: [University of Central Florida] At: 03:54 26 August 2010 International Journal of Electronics Figure 3. Proposed DCR Current Sensing topology for two-phase coupled inductors. The phase voltage VP1 given in Equation 1 is valid here and similarly VP2 can be given in the s-domain by: VP2 ¼ sðLk þ LM Þ iL2 sLM iL1 þ DCR iL2 ð4Þ Solving Equation 4 for iL2 and then substitution of iL2 into Equation 1 leads to the solution for iL1: iL1 ¼ VP1 ½s ðLk þ LM Þ þ DCR þ s LM VP2 ½s ðLk þ LM Þ þ DCR2 s2 L2M ð5Þ In the case that RC is not stuffed, the voltage across current sensing capacitor C for phase one can be expressed as: VC ¼ R1 1þsR1 C1 R1 1þsR1 C þ R2 VP1 þ R2 1þsR2 C1 R2 1þsR2 C þ R1 VP2 ð6Þ If the RC network is designed properly, VC should be able to represent the voltage drop across DCR of each phase. For phase one, the following equation will be satisfied: iL1 DCR ¼ VC ð7Þ 56 S. Xiao et al. Inserting Equation 5 into Equation 7 and substitution of VC in Equation 6 lead to: R1 R2 VP1 þ VP2 R1 þ R2 þ sR1 R2 C R1 þ R2 þ sR1 R2 C VP1 ½s ðLk þ LM Þ þ DCR þ s LM VP2 DCR ¼ ½s ðLk þ LM Þ þ sLM þ DCRðsLk þ DCRÞ ð8Þ Downloaded By: [University of Central Florida] At: 03:54 26 August 2010 Since the normal switching frequency of VR falls in the hundreds of kilohertz range, the term s(Lk þ LM) is usually much greater than DCR. Equation 8 can be decoupled into two equations by dropping off VP1 and VP2. The two equations are then rearranged as: Lk R1 1 þ s DCR Lk þ LM Lk þ 2LM ð9Þ Lk R2 1 þ s DCR LM ¼ R1 R2 L þ 2LM k ðR1 þ R2 Þ 1 þ s R1 þR2 C ð10Þ ðR1 þ R2 Þ ð1 þ R2 s RR11þR 2 CÞ ¼ Simplifying Equations 9 and 10 yields: R1 Lk þ LM Lk R1 R2 ¼ ¼ C R1 þ R2 Lk þ 2LM DCR R1 þ R2 ð11Þ The above derivation suggests that if the resistors and capacitors in the proposed topology are designed such that Equation 11 is satisfied, then by reversing the derivation procedure, Equation 7 can be obtained, which means that the voltage across C is a replica of the voltage across the inductor DCR, i.e., the phase current is duplicated. Therefore, Equation 11 can serve as the design equation for the proposed current sensing topology. For some applications in which the DCR voltage drop is too high or temperature compensation is desired, a scale-down resistor or thermal resistor RC is usually placed in parallel with C. In this case, VC is a scaled version of the DCR voltage. Letting the sensing gain be K, the following equations can be obtained: Lk R1 R2 RC R1 Lk þ LM ¼ C ¼ DCR R1 RC þ R2 RC þ R1 R2 R1 þ R2 Lk þ 2 LM ðR1 þ R2 Þ RC K¼ R1 RC þ R2 RC þ R1 R2 4. ð12Þ Sensitivity and mismatch analysis The above analysis has assumed ideal coupled inductors with known, matched coefficients. In practice, it is difficult to obtain accurate values of the parasitic 57 Downloaded By: [University of Central Florida] At: 03:54 26 August 2010 International Journal of Electronics resistance, which varies with frequency, proximity effects (and therefore current), temperature, etc. And it would not be expected to be balanced among windings in a given inductor. The other parameters such as leakage inductance and magnetising inductance have tolerance up to 30% and can also change with time as magnetic materials cycle and age (LC1740-R30R10A). With the tolerance and mismatch issues, the sensed current signal may be distorted. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate the sensitivity and mismatch effects on sensed currents. Since the tolerance of the RC sensing components is typically as low as 1%, the discussion will be focused on the coupled inductor coefficients only. Letting the variations of the leakage inductance, magnetising inductance, DCR to be dLk, dLM, dDCR and the resulted voltage deviation on sensing capacitor C to be dVC, respectively, then the effect of each specific coefficient on the sensed current can be analysed. By adding the variations into Equations 1 and 4, insertion of these equations into Equation 6 leads to the equation for VC with deviation. dVC can be solved by subtraction of VC from this equation. If the current sensing sensitivity ratio is defined as the sensing deviation dVC over the correct voltage VC on the sensing capacitor, then for leakage inductance variation dLk: dVC dLk 1 ¼ VC Lk 1 þ R1 þR2 ð13Þ s R1 R2 C For magnetising inductance, the sensitivity ratio is obtained as: dVC dLM R2 1 ¼ VC LM R1 R2 1 þ R1 þR2 ð14Þ s R1 R2 C The sensitivity ratio for DCR can be given as: dVC dDCR 1 ¼ DCR þ dDCR 1 þ sR1 R2 C VC ð15Þ R1 þR2 Equations 13, 14 and 15 suggest that coefficient variations result in current sensing errors and the errors vary with frequency. To demonstrate sensitivity of each coefficient, the coupled inductor LC1740-R30R10A from NEC/Tokin is employed as an example (LC1740-R30R10A). According to design equations in Equation 11, the current sensing values as well as the inductor coefficient are given in Table 1. Table 1. Coefficients of LC1740-R30R10A and current sensing values. Leakage inductance (nH) 110% + 30% Magnetising inductance (nH) DCR (mO) R1 (kO) R2 (kO) C (mF) 200% + 30% 0.4% + 5% 3.1 2 0.22 Downloaded By: [University of Central Florida] At: 03:54 26 August 2010 58 Figure 4. S. Xiao et al. Normalised sensitivity ratio for leakage inductance, magnetising inductance and DCR. Figure 5. Experimental results for proposed topology. System parameters: Vin ¼ 12 V, VO ¼ 1.2 V, LO ¼ LC1740-R30R10A from NEC/Tokin, CO ¼ 36 6 22 mF MLCC. Controller: ISL6266 from Intersil (X-axis: 20 V/div for channel 1 and channel 4, 10A O/div for channel 3, and 5 mV O/div for channel 2; Y-axis: 1 mS/div). International Journal of Electronics 59 Downloaded By: [University of Central Florida] At: 03:54 26 August 2010 Based on Equations 13, 14 and 15, normalised sensitivity ratio (sensitivity ratio over tolerance) of the coefficients can be plotted versus frequency in Mathcad as shown in Figure 4. It can be concluded from Figure 4 that: (1) The tolerance of magnetising inductance is amplified by around 1.8 times at high frequencies, indicating the AC portion of the sensed current waveform will be distorted if the magnetising inductance data is not accurate enough. However, it has little effect on the DC level of sensed current. (2) The deviation of sensed current is almost proportional to the leakage inductance tolerance at high frequencies. Similar to the magnetising inductance, it has limited impact on the DC current level. (3) This topology is sensitive to DCR tolerance at DC (low frequencies), and the sensed current deviation is nearly proportional to the DCR tolerance. At high frequencies, DCR tolerance has negligible effect on sensed current. As a common industry practice, a thermal resistor RC as shown in Figure 3 is usually placed close to the inductor to compensate the DCR temperature variation. Therefore, the DC current sensing error can be controlled within acceptable range if the topology is designed properly. The AC portion of sensed current may have errors that stem from leakage and magnetising inductance tolerance. Figure 6. Comparison of real phase current and sensed current by proposed topology (X-axis: 20 V/div for channel 1 and channel 4, 10A O/div for channel 3, and 5 mV O/div for channel 2; Y-axis: 1 mS/div). 60 Downloaded By: [University of Central Florida] At: 03:54 26 August 2010 5. S. Xiao et al. Experimental verification A 400 kHz two-phase VR with coupled inductors has been developed to verify the proposed topology. The component values and coefficients of the topology are listed in Table 1, where RC is not stuffed. The experimental results are shown in Figure 5. From top to bottom, the first waveform represents the sensed current by the proposed topology and the second waveform is the phase inductor current captured by a current probe, respectively. The two bottom waveforms are the PWM switching voltages. To investigate the current sensing error, the sensed current and real current in Figure 5 are overlapped as shown in Figure 6. From Figures 5 and 6, it is found that the sensed current agrees with the real phase current in terms of DC level. The AC portion (valley current) is distorted a little because of the tolerance of leakage and magnetising inductance. The high-frequency jitters on the sensed waveforms are random noise resulting from measurement. 6. Conclusion A current sensing topology for coupled inductors has been proposed in this article. By implementation of simple RC networks, the phase coupling information can be preserved. Mathematical derivation and design formula were presented in detail. Sensitivity and mismatch issues are addressed in terms of mathematical experimental results show that the proposed topology is able to sense real phase current with acceptable accuracy. References Chen, W., Lee, F.C., Zhou, X., and Xu, P. (1999), ‘‘Integrated Planar Inductor Scheme for MultiModule Interleaved Quasi-Square-Wave (QSW) DC/DC Converter’’, Power Electronics Specialists Conference, Charleston, SC, USA. Dallago, E., Passoni, M., and Sassone, G. (2000), ‘‘Lossless Current Sensing in Low-Voltage HighCurrent DC/DC Modular Supplies’’, Industrial Electronics IEEE Transactions on Volume 47, (Issue 6, Dec), 1249–1252. Dong, Y., Xu, M., and Lee, F.C. (2006), ‘‘DCR Current Sensing Method for Achieving Adaptive Voltage Positioning (AVP) in Voltage Regulators with Coupled Inductors’’ PESC, 1–7. Forghani-zadeh, H.P., and Rincon-Mora, G.A. (2002), ‘‘Current-Sensing Techniques for DC–DC Converters’’. Circuits and Systems, 2002. MWSCAS-2002, Vol. 2, II–577–II–580. Forghani-zadeh, H.P., and Rincon-Mora, G.A. (2005), ‘‘A Lossless, Accurate, Self-Calibrating Current-Sensing Technique for DC–DC Converters’’, IECON 2005, p. 6. Herbert, E. (2005), ‘‘Buck (or boost) Converter with Very Fast Output Current Transitions and Low Ripple Voltage’’, U.S. patent 6,897,641 B1. Hua, L., and Luo, S. (2006), ‘‘Design Considerations of Time Constant Mismatch Problem for Inductor DCR Current Sensing Method’’ APEC, 7. ‘‘ISL6327: Enhanced 6-Phase PWM Controller with 8-Bit VID Code and Differential Inductor DCR or Resistor Current Sensing’’, Datasheet of Intersil Corporation, available at http:// www.intersil.com ‘‘LC1740-R30R10A: 25A coupled inductors’’, Datasheet of NEC TOKIN, available at http:// www.nec-tokinamerica.com/ Ledenev, A.V., Porter, R.M., and Gurov, G.G. (2004), ‘‘Low Voltage High Current DC Computer Power System’’, US patent No. 6696823 B2. Advanced Energy industries, Inc. Li, J., Sullivan, C.R., and Schultz, A. (2002), ‘‘Coupled-Inductor Design Optimization for FastResponse Low-Voltage DC-DC Converters’’, APEC, 2, 817–823. Dallas, TX, USA. LinFinity Applications Note AN-7, ‘‘A simple current-sense technique eliminating a sense resistor’’, Jul. 1998, pp. 1–6. Downloaded By: [University of Central Florida] At: 03:54 26 August 2010 International Journal of Electronics 61 Ma, K.-W., and Lee, Y.-S. (1994), ‘‘Technique for Sensing Inductor and DC Output Currents of PWM DC-DC Converter’’, IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, 9(3), 346–354. ‘‘Maxwell Bridge’’, available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maxwell_bridge Pietkiewicz, A., and Tollik, D. (1998), Coupled-Inductor Current-Doubler Topology in PhaseShifted Full-Bridge DC-DC Converter in Telecommunications Energy Conference, 1998. INTELEC. Twentieth International, 4–8 Oct., 41–48. Schultz, A.M., and Sullivan, C.R. (2002), ‘‘Voltage Converter with Coupled Inductive Windings, and Associated Methods’’, U.S. Patent number 6,362,986, Volterra Semiconductor Corp. ‘‘Voltage Regulator-Down (VRD) 11.0 Processor Power Delivery Design uidelines for Desktop LGA775 Socket’’, available at http://www.intel.com Walters, M.M., et al. (1998). ‘‘DC-to-DC converter with inductor current sensing and related methods’’, US patent No. 5982160. Harris Corporation. Wong, P.-L., Wu, Q., Xu, P., Yang, B., and Lee, F.C. (2000), ‘‘Investigating Coupling Inductors in the Interleaving QSW VRM’’, APEC 2000, Fifteenth Annual IEEE, Volume: 2, 6–10 Feb., Vol. 2, 973–978. New Orleans, LA, USA. Wu, W., Lee, N.-C., and Schuellein, G. (2006), ‘‘Multi-Phase Buck Converter Design with TwoPhase Coupled Inductors’’ APEC, ’06, p. 6. Xiao, S., Qiu, W., Wu, T., and Batarseh, I. (2008). ‘‘Investigating effects of magnetizing inductance for coupled-inductor voltage regulators’’ APEC. Xu, M., Ying, Y., Li, Q., and Lee, F.C. (2007). ‘‘Novel Coupled-Inductor Multi-phase VRs’’ APEC, 113–119. Zhou, J., Xu, M., and Lee, F.C. (2005), ‘‘Small Signal Modeling of A High Bandwidth Voltage Regulator Using Coupled Inductors’’ PESC ’05, 2790–2796. Recife, Brazil. Zhou, X., Peng, X., and Lee, F.C. (1999). ‘‘A High Power Density, High Efficiency and Fast Transient Voltage Regulator Module with a Novel Current Sensing and Current Sharing Technique’’ APEC ’99, Fourteenth Annual Volume 1, 14–18 March 1999, Vol. 1, 289–294. Dallas, TX, USA.