Inventions in Russia: From Public Good to

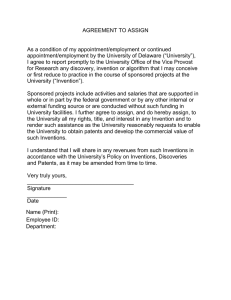

advertisement