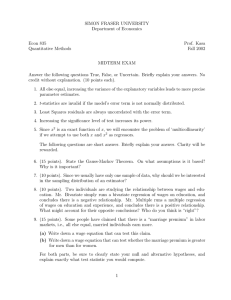

Market distortions or Efficient Institutions?

advertisement