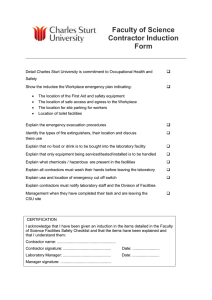

A principal`s guide to contracting to meet the Health and Safety in

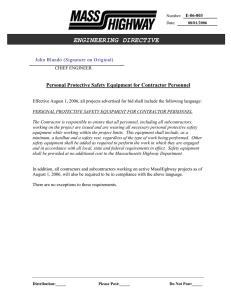

advertisement