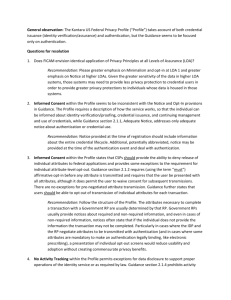

Introduction to Online Identity Management

advertisement