setting standards - Legal Education and Training Review

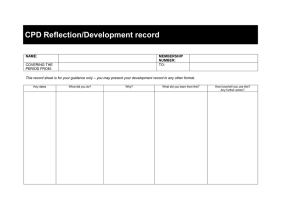

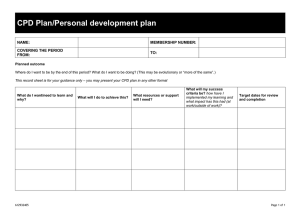

advertisement