pdf - arXiv.org

advertisement

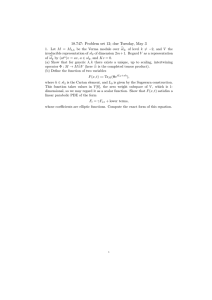

SCISSORS CONGRUENCE GROUPS AND THE THIRD HOMOLOGY OF SL2 OF

LOCAL RINGS AND FIELDS

arXiv:1309.5010v1 [math.KT] 19 Sep 2013

KEVIN HUTCHINSON

h i

Abstract. We describe the third homology of S L2 of local rings, over Z 12 , in terms of a refined Bloch group. We use this to derive a localization sequence for the third homology of S L2

of certain discrete valuation rings and to calculate the H3 of S L2 of higher-dimensional local

fields and their associated discrete valuation rings in terms of indecomposable K3 and scissors

congruence groups of intermediate residue fields.

1. Introduction

The study of the homology of special linear groups divides naturally into the stable and unstable cases. For a field F and for given n ∈ N when m is sufficiently large (see [25, 10]) the

groups Hn (SLm (F), Z) stabilize (in the sense that they become independent of m). These stable

homology groups embed as natural direct summands in the corresponding homology of the general linear group Hn (GLm (F), Z) and their calculation is therefore closely tied to the calculation

of the homology of the general linear group and to algebraic K-theory. When m is small, by

contrast, it usually happens that neither the stabilization maps nor the map to the homology of

the general linear group is injective and the kernels of these maps are interesting invariants of

the field.

For a field or local ring A, the structure of H2 (SLm (A), Z) is well-understood, thanks to the

Theorem of Matsumoto-Moore ([13, 17]), and the results of W. van der Kallen ([24] and A.

Suslin ([22]): Stability begins at m = 3 and H2 (SLm (A), Z) K2 (A) = K2M (A) for all m ≥ 3.

For a field F, the map H2 (SL2 (F), Z) → H2 (SL3 (F), Z) is surjective and the kernel is naturally

I 3 (F), the third power of the fundamental ideal of the Witt ring of the field F.

For the groups H3 (SLm (F), Z), stability also begins at m = 3 and

H3 (SLm (F), Z) K3 (F)/{−1} · K2 (F)

for all m ≥ 3 ([23, 9]). The map H3 (SL2 (F), Z) → H3 (SL3 (F), Z) has cokernel isomorphic to

2K3M (F) and image isomorphic - up to 2-torsion - to K3ind (F) ([9]). The group H3 (SL2 (F), Z)

has been much studied because of its connections with K-theory, the dilogarithm function,

hyperbolic geometry and other topics ([1, 20, 23, 27, 5, 2, 18]). However, its structure for

general fields or rings is far from being understood. For instance the structure of H3 (SL2 (Q), Z)

is not yet known (but see [8]).

For any field F there is a natural surjective homomorphism

(1)

//

H3 (SL2 (F), Z)

Date: September 20, 2013.

1991 Mathematics Subject Classification. 19G99, 20G10.

Key words and phrases. K-theory, Group Homology .

1

K3ind (F)

2

KEVIN HUTCHINSON

from the third homology of SL2 (F) to the indecomposable K3 of the field (see [9] for infinite

fields and [6] for finite fields). This map is an isomorphism when F is algebraically, or even

quadratically, closed ([20, 14]).

In fact the map (1) is naturally a map of RF -modules where RF is the group ring Z[F × /(F × )2 ].

The action of RF on K3ind (F) is trivial, while

the# square class hai of the element a ∈ F × acts

"

a 0

on the left via conjugation by the matrix

(or more generally by any 2 × 2 matrix with

0 1

determinant a). It turns out – see [4, 14] – that essentially (i.e. up to some possible 2-torsion) the

only obstruction to the injectivity of the map (1) is the nontriviality or otherwise of the action

of RF on H3 (SL2 (F), Z); i.e. there is an induced isomorphism

h i

h i

H3 (SL2 (F), Z 21 )F × K3ind (F) 12 .

Equivalently we have

Ker(H3 (SL2 (F), Z

h i

1

2

) → K3ind (F)

h i

1

2

) = IF H3 (SL2 (F), Z

h i

1

2

)

where IF is the augmentation ideal in the group algebra RF .

Now for a field F, K3ind (F) is closely related to B(F), the Bloch group of F ([3], [23]). This is a

natural subgroup of the scissors congruence group P(F) (or pre-Bloch group in the terminology

of [23]), which is described by a presentation where the relations are derived from the 5-term

functional equation of dilogarithm function.

In [6] we introduced an RF -module RB(F), the refined Bloch group of the field F, which is

closely related to H3 (SL2 (F), Z) – for details see section 2.4 below – and which can be explicitly

calculated in some interesting cases ([8]). RB(F) surjects naturally onto B(F) with kernel

RB0 (F) and we have for any field F

h i

h i

h i

RB0 (F) 12 = IF RB(F) 12 = IF H3 (SL2 (F), Z 21 ).

The main purpose of the present article is firstly to generalize the results of [6] and [8] from

fields to local rings – including the case of finite residue fields – and then to apply these results

to compare the third homology of S L2 of local rings with that of their fields of fractions and

with related invariants of their residue fields. This leads

h ito what we call a localization sequence

for the third homology of S L2 , with coefficients in Z 21 , of a certain (quite restricted) class of

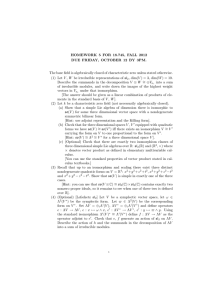

discrete valuation rings. This takes the form of a short exact sequence

h i

h i

h i

g 1 (F) 1 → 0

(2)

0 → H3 (SL2 (A), Z 1 ) → H3 (SL2 (K), Z 1 ) → RP

2

2

2

where A is a discrete valuation ring with field of fractions K and residue field F. In fact, the

sequence is defined for any discrete valuation ring and we would expect it to be exact for a

larger class of rings than those to which our methods of proof apply.

g 1 (F) is essentially a refined version of the classical scisIn this exact sequence, the functor RP

sors congruence group of the field F. In particular, we show that for a large class of higherdimensional local fields it can be expressed as a direct sum of the scissors congruence group of

the field and of copies of the scissors congruence groups of the intermediate residue fields.

We refer to the sequence (2) as a localization sequence because of an analogy with K-theory

and related functors. For example, in a forthcoming article ([7]) we show that for an infinite

field F there is a natural (split) short exact sequence

h i

h i

h i

g 1 (F) 1 → 0.

0 → H3 (SL2 (F), Z 1 ) → H3 (SL2 (F[T, T −1 ]), Z 1 ) → RP

2

2

2

(There is also a corresponding statement for H2 (SL2 (F), Z) where the associated functor is

Milnor-Witt K1 .)

H3 of SL2 of local rings

3

The article is laid out as follows:

In section 2 we review the definitions of (refined) scissors congruence groups and Bloch groups

of commutative rings and recall the required results from [6] and [8].

In section 3 we prove (Theorem 3.22) that for local rings A with sufficiently large residue field

there is a natural short exact sequence

h i

h i

h i

0 → tor(µA , µA ) 21 → H3 (SL2 (A), Z 12 ) → RB(A) 12 → 0.

The proof follows the same route as the proof of the corresponding theorem for fields in [6], but

we supply all the necessary details for the convenience of the reader.

In section 4, we consider certain submodules and quotient modules of the refined scissors

congruence group RP(A) which play an important role in our calculations. Again, we are here

following a route already covered in the case of fields. Only small adaptations are needed to

extend the results for fields to the more general case of local rings, but we include (most) details

for the reader’s convenience. In particular, the key identity hhxii DA = ψ1 (x) − ψ2 (x) in RP(A)

(see Theorem 4.19) is crucial to our later calculations.

In section 5 we re-visit the specialization homomorphism for the refined Bloch group of a

field with valuation which was introduced in [8] and used to calculate the third homology of

S L2 of local and global fields. The small technical improvement here is that we re-prove the

[ F , with the

specialization theorem replacing the original target of this map, the module RP(k)

g F (Theorem 5.2). (The improvement is not hugely significant: there is a

larger module RP(k)

g F → RP(k)F whose kernel is annihilated by 3.)

surjective map RP(k)

In section 6 we use the specialization homomorphism to compare the refined Bloch group

of a field with discrete valuation and finitely many square classes with the refined scissors

congruence group of the residue field. In this section, we also compare the refined scissors

congruence group of a local ring to that of its residue field. We apply these results and Theorem

3.22 to calculate the third homology of S L2 of some higher-dimensional local fields, greatly

generalizing the main result of [8]. The restriction to fields with finitely many square classes

here is primarily an artefact of our method of proof: All of the objects of study are modules

over the group of square classes of the field or local ring, and we compare related modules by

comparing the associated eigenspaces for the characters of the group of square classes.

In section 7 we use the results of the previous section to prove the localization theorem (Theorem 7.2). Although we would expect the theorem to be much more widely valid, our methods

of proof restrict us to a very small class of discrete valuation rings; those whose residue field

either has at most two square classes or has finitely many square classes and a discrete valuation

satisfying a number of conditions.

Finally, in section 8 we detail a range of particular cases of the results of sections 6 and 7.

2. Scissors congruence groups and Bloch Groups

2.1. Preliminaries and Notation. For a commutative ring A, we let U A denote the group of

units of A and we let GA denote the multiplicative group, U A /U A2 , of square classes of U A . For

x ∈ U A , we will let hxi ∈ GA denote the corresponding square class. Let RA denote the integral

group ring Z[GA ] of the group GA . We will use the notation hhxii for the basis elements, hxi − 1,

of the augmentation ideal IA of RA .

For any a ∈ U A , we will let pa+ and pa− denote respectively the elements 1 + hai and 1 − hai in

RA .

4

KEVIN HUTCHINSON

h i

1

2

h i

1

2

. For an integer n, we will let n0

h i

denote the odd part of n. Thus if G is a finite abelian group of order n, then G 21 is a finite

abelian group of order n0 .

We let ea+ and ea− denote respectively the mutually orthogonal idempotents

h i

pa

pa

1 + hai

1 − hai

, ea− := − =

∈ RA 12 .

ea+ := + =

2

2

2

2

(Of course, these operators depend only on the class of a in GA .)

For an abelian group G and n ∈ N, G[n] will denote the subgroup {g ∈ G | ng = 0}.

For any abelian group G we will let G

denote G ⊗ Z

2.2. Indecomposable K3 . Let A be a either a local ring or a field. Let K• (A) denote the

Quillen K-theory of A and let K•M (A) be the Milnor K-theory. There is a natural homomorphism of graded rings K•M (A) → K• (A). Indecomposable K3 of A is the group K3ind (A) :=

Coker(K3M (→)K3 (A)). We will require the following theorem from K-theory:

Theorem 2.1. Let A be discrete valuation ring with field of fractions K and residue field F.

Suppose that either char(K) = char(F) or that F is finite. Then the inclusion A → K induces an

isomorphism K3ind (A) K3ind (K).

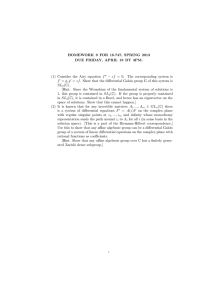

Proof. Let F be the residue field of A and let π be a uniformizer. There is a commutative

diagram with exact columns

0

0

/

0

K3M (K)

/

K3 (A)

K3ind (A)

/

K3M (A)

/

K3 (K)

δπ

δπ

/

/

K2M (F)

/

0

=

K2 (F)

/

0

K3ind (K)

0

The exactness of the top row is well-known (see [26, Corollary 6.6.2] for example). The second

row is exact by Gersten’s conjecture, which is known for the case of equicharacteristic discrete valuation rings or discrete valuation rings with finite residue fields (see, for example, [26,

Corollary 6.7.2, Corollary 6.9.2]). The result follows by the snake lemma.

2.3. Scissors congruence groups and Bloch groups. For a commutative ring A, let WA denote the set {u ∈ U A : 1 − u ∈ U A }. The scissors congruence group or pre-Bloch group, P(A), is

the group generated by the elements [x], x ∈ WA , subject to the relations

"

# "

#

y

1 − x−1

1−x

R x,y : [x] − y +

−

+

for all x, y, x/y ∈ WA .

x

1 − y−1

1−y

Given an abelian group G we let S2Z (G) denote the group

G ⊗Z G

< x ⊗ y + y ⊗ x|x, y ∈ G >

H3 of SL2 of local rings

5

and, for x, y ∈ G, we denote by x ◦ y the image of x ⊗ y in S2Z (G).

For a commutative ring A, the map

λ : P(A) → S2Z (U A ),

[x] 7→ (1 − x) ◦ x

is well-defined, and the Bloch group of A, B(A) ⊂ P(A), is defined to be the kernel of λ.

For a field F, the Bloch group is known to be closely related to the indecomposable K3 : There

is a natural exact sequence

0 → TorZ]

(µ , µ ) → K ind (F) → B(F) → 0

1

F

F

3

where TorZ1]

(µF , µF ) is the unique nontrivial extension of TorZ1 (µF , µF ) by Z/2. (See Suslin [23]

for infinite fields and [6] for finite fields.)

2.4. The refined Bloch group and H3 (SL2 (F), Z). For any field F there is a natural surjective

homomorphism

(3)

H3 (SL2 (F), Z) → K3ind (F).

When F is quadratically closed (i.e. when GF = 1) this map is an isomorphism.

However, for any commutative ring A, the group extension

1 → SL2 (A) → GL2 (A) → U A → 1

induces an action – by conjugation – of U A on H• (SL2 (A), Z) which factors through GA .

For a field F, it can be shown that the map (3) induces an isomorphism

h i

h i

H3 (SL2 (F), Z 21 )GF K3ind (F) 12

(see [14]), but – as our calculations, in [8] and below, show – the action of GF on H3 (SL2 (F), Z)

is in general non-trivial.

Thus H3 (SL2 (A), Z) is naturally an RA -module, and for general fields or rings, in order to give

a Bloch-type description of it, we must incorporate the RA -module structure at each stage of the

process.

The refined scissors congruence group or refined pre-Bloch group, RP(A), of a commutative

ring A which has at least 4 elements, is the RA -module with generators [x], x ∈ WA subject to

the relations

"

#

y D

E " 1 − x−1 #

1−x

−1

S x,y : 0 = [x] − y + hxi

− x −1

+ h1 − xi

, for all x, y, y/x ∈ WA

x

1 − y−1

1−y

Of course, from the definition it follows immediately that P(A) = (RP(A))GA = H0 (GA , RP(A)).

Let Λ = (λ1 , λ2 ) be the RA -module homomorphism

RP(A) → I2A ⊕ S2Z (U A )

where λ1 : RP(A) → I2A is the map [x] 7→ hh1 − xii hhxii, and λ2 is the composite

RP(A)

//

P(A)

λ

/

S2Z (U A ).

It can be shown that Λ is well-defined.

The refined Bloch group of the commutative ring A (with at least 4 elements) to be the RA module

RB(A) := Ker(Λ : RP(A) → I2A ⊕ S2Z (U A )).

Remark 2.2. The functor RP1 (A) := Ker(λ1 ) will also play an essential role in what follows.

6

KEVIN HUTCHINSON

We recall some results from [6]: The main result there is

Theorem 2.3. Let F be any field.

(1) If F is infinite, there is a natural complex

0 → TorZ1 (µF , µF ) → H3 (SL2 (F), Z) → RB(F) → 0.

which is exact everywhere except possibly at the middle term. The middle homology is

annihilated by 4.

In particular, for any infinite field there is a natural short exact sequence

h i

h i

h i

0 → TorZ1 (µF , µF ) 12 → H3 (SL2 (F), Z 21 ) → RB(F) 12 → 0.

(2) If F = Fq is finite of characteristic p, there is a natural short exact sequence

h i

0 → TorZ1]

(µF , µF ) → H3 (SL2 (F), Z 1p ) → B(F) → 0.

h i

and furthemore H3 (SL2 (F), Z) = H3 (SL2 (F), Z 1p ) for q > 27.

Now for any field F, let

H3 (SL2 (F), Z)0 := Ker(H3 (SL2 (F), Z) → K3ind (F))

and

RB0 (F) := Ker(RB(F) → B(F))

The following is Lemma 5.2 in [6].

Lemma 2.4. Let F be an infinite field. Then

h i

h i

(1) H3 (SL2 (F), Z 12 )0 = RB0 (F) 12

h i

h i

h i

h i

(2) H3 (SL2 (F), Z 21 )0 = IF H3 (SL2 (F), Z 12 ) and RB0 (F) 12 = IF RB(F) 12 .

(3)

h i

h i

h i

H3 (SL2 (F), Z 21 )0 = Ker(H3 (SL2 (F), Z 12 ) → H3 (SL3 (F), Z 12 ))

h i

h i

= Ker(H3 (SL2 (F), Z 12 ) → H3 (GL2 (F), Z 12 ))

Lemma 2.5. Ifh the

i field F is quadratically closed, real-closed or finite then IF RB(F) = 0, and

1

hence RB0 (F) 2 = 0 also.

Proof. Since H3 (SL2 (F), Z) maps onto RB(F) as an RF -module, this follows from the fact that

GF acts trivially on H3 (SL2 (F), Z) in each of these cases.

For a quadratically closed field this is vacuously true.

This result is proved by Parry and Sah in [19] for the field R, but their argument extends easily

to any real-closed field.

For finite fields, the relevant result is Lemma 3.8 of [6].

Furthermore, the calculations in [6], sections 5 and 7, show that

Lemma 2.6. Let q be a power of a prime. Then

(

Z/(q + 1)/2, q odd

RB(Fq ) = B(Fq ) Z/(q + 1),

q even

h i

h i

and B(Fq ) 21 = P(Fq ) 12 .

H3 of SL2 of local rings

7

3. The third homology of SL2 of local rings

In this section, we generalize Theorem 2.3 to local rings with sufficiently large residue field.

3.1. Homological intrepretation of RP(A). Let A be a commutative ring. A row vector u =

(u1 , u2 ) ∈ A2 is said to be unimodular if Au1 + Au1 = A. Equivalently, u is unimodular if there

exists v ∈ A2 such that

" #

u

∈ GL2 (A).

v

We let U2 = U2 (A) denote the set of 2-dimensional unimodular row vectors of A. U2 is a right

GL2 (A)-set. In particular this induces an action of U A = Z(GL2 (A)) acting as multiplication by

scalars.

Let

(

"

#

)

ui

gen

gen

n

Un = Un (A) := (u1 , . . . , un ) ∈ U2 :

∈ GL2 (A) for all i , j .

uj

U An acts entry-wise on Ungen and we let Xn = Xn (A) = Ungen /U An . Observe that Ungen and Xn are

right GL2 (A)-sets (with the natural diagonal action).

In particular, X1 = U2 /U A and Xn ⊂ X1n . If u = (u1 , u2 ) ∈ U2 we will denote the corresponding

class in X1 by ū or [u1 , u2 ].

We have two natural injective maps from A to X1 :

ι+ : A → X1 , a 7→ a+ := [a, 1] and ι− : A → X1 , a 7→ a− := [1, a]

Clearly, a+ = b− in X1 if and only if a, b ∈ U A and b

in X1 under the map ι+ .

If (u, v) ∈ U2gen , we set

"

u

d(u, v) := det

v

and

" #−1 "

u

0

·

T u,v :=

v

d(u, v)

= a−1 . We will identify U A with its image

#!

∈ UA

−1

0

#

∈ SL2 (A).

Thus, for (u, v) ∈ U2gen with d = d(u, v) we have

u · T u,v = (0, −1) and v · T u,v = (d, 0) in U2

and hence

ū · T u,v = 0+ , v̄ · T u,v = 0− in X1 .

Let φ : U3gen → X1 be the map defined by

φ(u, v, w) := w̄ · T u,v ∈ X1 .

Lemma 3.1. Let A be a commutative ring and let (u, v, w) ∈ U3gen . Then

!

d(u, w) · d(u, v)

∈ U A ⊂ X1 .

φ(u, v, w) =

d(v, w)

+

Proof. A straightforward direct calculation gives

w · T u,v

!

d(v, w)

= d(u, w),

∈ U2 .

d(u, v)

8

KEVIN HUTCHINSON

Corollary 3.2. Let A be a commutative ring and let (u, v, w) ∈ U3gen .

(1) For all a, b, c ∈ U A we have

φ(u · a, v · b, w · c) = φ(u, v, w) · a2 .

(2) For all X ∈ GL2 (A) we have

φ ((u, v, w) · X) = φ(u, v, w) · det(X).

Now, for n ≥ 1, let

Yn = Yn (A) := {(y1 , . . . , yn ) ∈ U An : yi − y j ∈ U A for all i , j}.

We will consider Yn as a right U A -set via (y1 , . . . , yn ) · a := (y1 a, . . . , yn a).

For n ≥ 3, let Φn : Ungen → U An be the map

Φn (u1 , . . . , un ) := (φ(u1 , u2 , u3 ), . . . , φ(u1 , u2 , ui ), . . . , φ(u1 , u2 , un )) .

Lemma 3.3. For all (u1 , . . . , un ) ∈ Ungen , we have Φn (u1 , . . . , un ) ∈ Yn−2 .

Proof. For 3 ≤ i ≤ n, let yi := φ(u1 , u2 , ui ). Let 3 ≤ i < j ≤ n. Then

"

#

"

#

ui

ui

∈ GL2 (A) =⇒

· T u1 ,u2 ∈ GL2 (A).

uj

uj

But

"

#

"

#"

#

ui

yi 1

a 0

· T u1 ,u2 =

uj

yj 1

0 b

for some a, b ∈ U A . On taking the determinant, it follows that yi − y j ∈ U A .

From Corollary 3.2 we immediately deduce:

Lemma 3.4. Let (u1 , . . . , un ) ∈ Ungen .

(1) For all a1 , . . . , an ∈ U A we have

Φn (u1 · a1 , . . . , un · an ) = Φn (u1 , . . . , un ) · a21 .

(2) For all X ∈ GL2 (A) we have

Φn ((u1 , . . . , un ) · X) = Φn (u1 , . . . , un ) · det(X).

It follows that Φn induces a well-defined map of orbit sets (which we will continue to denote

Φn )

Xn /SL2 (A) → Yn−2 /U A2 .

Furthermore, this is a map of right GA -sets (noting that the matrix X ∈ GL2 (A) acts via the

square class of det(X) on the left).

Proposition 3.5. For all n ≥ 3, Φn induces a bijection of GA -sets

Xn /SL2 (A) ↔ Yn−2 /U A2 .

Proof. Let Ψn : Yn−2 → Ungen be the map

(y3 , . . . , yn ) 7→ ((0, −1), (1, 0), (y3 , 1), . . . , (yn , 1)) .

Then Φn ◦ Ψn = IdYn−2 since T (0,−1),(1,0) is the identity matrix.

Now let Ψ̄n be the induced map from Yn−2 to Xn , given by the formula

(y3 , . . . , yn ) 7→ (0+ , 0− , (y3 )+ , . . . , (yn )+ ) .

H3 of SL2 of local rings

9

For any y ∈ A and a ∈ U A we have

#

"

a 0

= [ya, a−1 ] = [ya2 , 1] = (ya2 )+ in X1 .

[y, 1]

0 a−1

It follows that Ψ̄n induces a well-defined map Yn−2 /U A2 → Xn /SL2 (A) satsifying Φn ◦ Ψ̄n =

IdYn−2 /UA2 .

It remains to show that Ψ̄n : Yn−2 /U A2 → Xn /SL2 (A) is surjective: If (u1 , . . . , un ) ∈ Ungen then in

Xn /SL2 (A) we have

(ū1 , . . . , ūn ) = (ū1 , . . . , ūn ) · T u1 ,u2 = (0+ , 0− , (y3 )+ , . . . , (yn )+ ) = Ψ̄n (y3 , . . . , yn )

where yi = φ(u1 , u2 , ui ) for i ≥ 3.

Taking the quotient set for the action of GA on both sides, we deduce:

Corollary 3.6. For n ≥ 3, Φn induces a natural bijection

Xn /GL2 (A) ↔ Yn−2 /U A .

For n ≥ 1, we let

Zn = Zn (A) := {(z1 , . . . , zn ) ∈ WAn : zi /z j ∈ WA for all i , j}

and we let Z0 = Z0 (A) := {1}.

We observe that for n ≥ 1 there is a natural bijection of U A -sets

!!

y2

yn

Yn ↔ U A × Zn−1 , (y1 , . . . , yn ) ↔ y1 ,

,...,

y1

y1

(where U A acts on the first factor of the right-hand side). Thus, taking quotient sets for the

action of U A2 and U A , we obtain:

Corollary 3.7. For all n ≥ 3 we have natural bijections

Xn /SL2 (A) ↔ GA × Zn−3

Xn /GL2 (A) ↔ Zn−3

Remark 3.8. Retracing our steps above, an explicit formula for the first bijection is

!!

φ(u1 , u2 , u4 )

φ(u1 , u2 , un )

(ū1 , . . . , ūn ) 7→ hφ(u1 , u2 , u3 )i ,

,...,

φ(u1 , u2 , u3 )

φ(u1 , u2 , u3 )

*

+

!!

d(u1 , u3 )d(u1 , u2 )

d(u1 , u4 )d(u2 , u3 )

d(u1 , un )d(u2 , u3 )

=

,

,...,

d(u2 , u3 )

d(u2 , u4 )d(u1 , u3 )

d(u2 , un )d(u1 , u3 )

and hence the formula for the second is

!

d(u1 , u4 )d(u2 , u3 )

d(u1 , un )d(u2 , u3 )

(ū1 , . . . , ūn ) 7→

,...,

.

d(u2 , u4 )d(u1 , u3 )

d(u2 , un )d(u1 , u3 )

Remark 3.9. If A = F is a field, then clearly X1 = (F 2 \ {0})/F × = P1 (F) and more generally Xn

is naturally the set of n-tuples of distinct points of P1 (F). On the other hand, WF = F × \ {1} =

P1 (F) \ {∞, 0, 1} and Zn consists of n-tuples of distinct points of F × \ {1}.

The point x ∈ F is identified with the point of P1 (F) represented by (x, 1). Since d((x, 1), (y, 1)) =

x − y, the bijection Xn /GL2 (F) ↔ Zn−3 is thus given by the formula

(x1 , . . . , xn ) 7→ ({x1 : x2 : x3 : x4 }, . . . , {x1 : x2 : x3 : xn })

10

KEVIN HUTCHINSON

where

{x1 : x2 : x3 : x4 } =

(x1 − x4 )(x2 − x3 )

(x1 − x2 )(x3 − x4 )

is the classic cross ratio.

Corollary 3.10. For all n ≥ 3 there are natural isomorphisms of RA -modules

Z[Xn ]SL2 (A) RA [Zn−3 ]

and natural isomorphisms of Z-modules

Z[Xn ]GL2 (A) Z[Zn−3 ].

Proof. If G is a group and if X is a right G-set, then for any ring R there is a natural isomorphism

R[X]G R[X/G], x̄ 7→ x̄.

Thus, for n ≥ 3,

Z[Xn ]SL2 (A) Z[Xn /SL2 (A)] Z[GA × Zn−3 ] Z[GA ][Zn−3 ] = RA [Zn−3 ].

For n ≥ 1, let δn : Z[Xn+1 ] → Z[Xn ] be the simplicial boundary map

(ū1 , . . . , ūn+1 ) 7→

n+1

X

b̄i , . . . , ūn+1 )

(−1)i+1 (ū1 , . . . , u

i=1

and let A(A) := Coker(δ4 ). Note that (Z[Xn ], δn ) is a complex of GL2 (A)-modules and that A(A)

is thus also a GL2 (A)-module.

Proposition 3.11. For any commutative ring A, RP(A) A(A)SL2 (A) as RA -modules, and

P(A) A(A)GL2 (A) as Z-modules.

Proof. By right exactness of coinvariants, A(A)SL2 (A) is naturally identified with the cokernel of

the map δ̄4 : Z[X5 ]SL2 (A) → Z[X4 ]SL2 (A) of RA -modules induced by δ4 . Now

Z[X5 ]SL2 (A) RA [Z2 ] and Z[X4 ]SL2 (A) RA [Z1 ],

and, under these identifications, the map δ̄4 is described as follows: (z1 , z2 ) ∈ RA [Z2 ] corresponds to (1, z1 , z2 ) ∈ Y3 /U A2 and this in turn corresponds to the element (0+ , 0− , 1+ , (z1 )+ , (z2 )+ ) ∈

Z[X5 ]SL2 (A) . The image of this under δ̄4 is

(0− , 1+ , (z1 )+ , (z2 )+ )−(0+ , 1+ , (z1 )+ , (z2 )+ )+(0+ , 0− , (z1 )+ , (z2 )+ )−(0+ , 0− , 1+ , (z2 )+ )+(0+ , 0− , 1+ , (z1 )+ , (z2 )+ )

in Z[X4 ]SL2 (A) . Recalling that (ū1 , . . . , ū4 ) ∈ Z[X4 ]SL2 (A) corresponds to

*

+

!

d(u1 , u3 )d(u1 , u2 ) d(u1 , u4 )d(u2 , u3 )

∈ RA [Z1 ]

d(u2 , u3 )

d(u2 , u4 )d(u1 , u3 )

and observing that d(a+ , b+ ) = a − b and d(0− , a+ ) = 1 for all a , b ∈ A, we see that

! D

!

!

E 1 − z−1

1 − z1

z2

1

−1

δ̄4 (z1 , z2 ) = h1 − z1 i

− z1 − 1

+ hz1 i

− (z2 ) + (z1 ) ∈ RA [Z1 ].

1 − z2

z1

1 − z−1

2

Thus the map RA [Z1 ] → RP(A), (z) 7→ [z] induces an isomorphism

Coker(δ̄4 ) RP(A).

H3 of SL2 of local rings

11

Remark 3.12. We will call the (composite) map

d(u1 , u3 )d(u1 , u2 )

Z[X4 ] → RA [Z1 ] → RP(A), (ū1 , . . . , ū4 ) 7→

d(u2 , u3 )

*

+

d(u1 , u4 )d(u2 , u3 )

d(u2 , u4 )d(u1 , u3 )

!

the refined cross ratio map, and will denote it by cr. In the special case where ui = ι+ (xi ) for

xi ∈ A, it takes the form

*

#

+"

(x1 − x3 )(x1 − x2 ) (x1 − x4 )(x2 − x3 )

(x1 , x2 , x3 , x4 ) 7→

.

x2 − x3

(x1 − x2 )(x3 − x4 )

3.2. The isomorphism Hn (T, Z) Hn (B, Z). In order to prove Proposition 3.19 below, we

follow the strategy of Suslin’s proof of Theorem 1.8 in [21].

Lemma 3.13. ([21, LemmaQ1.1] ) Suppose that φ1 , . . . , φm : k → F are field embeddings such

that for any x ∈ k× we have mi=1 φi (x) = 1. Then k is a finite field of order p f with m ≥ (p−1)· f .

Remark 3.14. This simple but useful result can be extended in many directions. For example:

(See [11, Lemma 2.2.4]) Let A be a ring with many units. Let B be anyQ

ring. For any m ≥ 1,

there do not exist ring homomorphisms φ1 , . . . , φm : A → B satisfying mi=1 φi (x) = 1 for all

x ∈ UA.

Local rings with infinite residue fields are rings with many units, but we will want to include

the case of local rings with finite residue field below.

Corollary

Suppose that φ1 , . . . , φm : k → F are field embeddings such that for any x ∈ k×

Q3.15.

m

we have i=1 φi (xr ) = 1. Then k is a finite field of order p f and mr = (p − 1) · t for some t ≥ f .

Q

Q

Q

Proof. We have 1 = mi=1 φi (xr ) = mi=1 φi (x)r := mr

i=1 ψi (x), and thus k is finite of characteristic

p > 0 and mr ≥ (p − 1) f by Lemma 3.13.

Q

On the other hand, if a ∈ F p ⊂ k is a primitive root modulo p, then 1 = i φi (ar ) = amr and

thus p − 1|mr.

Corollary 3.16. Let A be a local ring with maximal ideal M and residue field k. Suppose

that

from A to the field F satisfying

Qm r ≥ r 1 and φ1 , . . . , φm : A → F are homomorphisms

f

i=1 φi (u ) = 1 for all u ∈ U A . Then k is a finite field with p elements and mr = (p − 1)t where

t ≥ f . In particular, (p − 1) f ≤ mr.

Proof. F must have positive characteristic, for otherwise we can choose 1 < n ∈ U A ∩ Z, and

the hypothesis gives nmr = 1 in F.

Let char(F) = p > 0. Replacing A by A/pA if necessary, we can assume that A is an F p algebra. We complete the proof by showing that M ⊂ Ker(φi ) for all i (and hence that the φi

factor through k):

Let x ∈ M. For i = 1, . . . , m, let xi = φi (x) ∈ F. If f (T ) ∈ F p [T ] satisfies f (0) , 0, then

f (x) ∈ U A . In this case we have

m

m

Y

Y

r

1=

φi ( f (x)) =

f (xi )r .

i=1

i=1

Thus, let I be the ideal of F p [T 1 , . . . , T m ] generated by the set

m

Y

r

{

f (T i ) − 1 | f (T ) ∈ F p [T ] with f (0) , 0}.

i=1

Let V be the corresponding variety. Then (x1 , . . . , xm ) ∈ V(F).

12

KEVIN HUTCHINSON

We observe that (0, . . . , 0) ∈ V if and only if p − 1|mr.

On the other hand, suppose that (a1 , . . . , am ) ∈ F̄mp is algebraic and that Q

a j , 0 for some j. Then

there exists f (T ) ∈ F p [T ] with f (0) , 0 and f (a j ) = 0. It follows that i f (ai )r = 0 and hence

(a1 , . . . , am ) < V(F̄ p ). Thus

(

{0}, p − 1|mr

V(F̄ p ) =

∅,

otherwise.

It follows from the Nullstellensatz that the ideal, J, of V in F̄ p [T 1 , . . . , T m ] is given by

(

p − 1|mr

hT 1 , . . . , T m i ,

J=

F̄ p [T 1 , . . . , T m ], otherwise.

and hence, for any field K we have

(

V(K) =

{0}, p − 1|mr

∅,

otherwise.

Since (x1 , . . . , xm ) ∈ V(F), it follows that p − 1|mr and xi = φi (x) = 0 for all i.

For r ≥ 1, we denote by A(r) the Z[U A ]-module obtained by making u ∈ U A act on A as

multiplication by ur .

Lemma 3.17. Let m, r ≥ 1. Let n1 , . . . , nk satisfy n1 + · · · nk = m and ni ≥ 1. Let A be a local

ring with residue field k. If k is finite of order p f we suppose that mr < (p − 1) f .

Let T n (A(r)) denote either ∧nZ (A(r)) or SymnZ (A(r)), considered as U A modules with the diagonal action.

Then

Hi (U A , T n1 (A(r)) ⊗ · · · ⊗ T nk (A(r))) = 0

for all i ≥ 0.

Proof. This follows from Corollary 3.16 by the same argument verbatim as that by which Suslin

proves Corollary 1.6 from Lemma 1.1 in [21].

Lemma 3.18. Let m, r ≥ 1. Let A be a local integral domain with residue field k. If k is finite of

order p f we suppose that mr < (p − 1) f .

For all i ≥ 0 we have

Hi (U A , Hm (A(r), Z)) = 0.

Proof. If char(A) = 0, then Hm (A(r), Z) = ∧mZ (A(r)) and the statement follows at once from

Lemma 4.6.

Otherwise A is an F p -algebra for some p > 0. Then Hm (A(r), F p ) is a direct sum of modules of the form ∧Zs (A(r)) ⊗ SymtZ (A(r)) with s + t ≤ m. It follows from Lemma 4.6 that

Hi (U A , Hm (A(r), F p )) = 0.

On the other hand, the short exact sequence

0

/

p

Z

/

Z

/

Z/pZ = F p

/

0

induces a long exact homology sequence for H• (A(r), ), which decomposes into short exact

sequences

0 → Hk (A(r), Z) → Hk (A(r), F p ) → Hk−1 (A(r), Z) → 0 (k ≥ 2)

and an isomorphism

H1 (A(r), Z) A(r) H1 (A(r), F p ).

H3 of SL2 of local rings

13

The vanishing of Hi (U A , Hm (A(r), Z)) for all i ≥ 0 then follows from a straightforward induction

on m.

We let T = T (A) denote the subgroup of SL2 (A) consisting of diagonal matrices:

#

)

("

u 0

| u ∈ UA .

T (A) :=

0 u−1

Thus T (A) U A . We let B = B(A) denote the subgroup consisting of lower triangular matrices:

#

)

("

u a

| u ∈ UA, a ∈ A .

B(A) :=

0 u−1

Thus there is natural (split) group extension

(4)

1→V →B→T →1

where

("

V = T (A) :=

1 a

0 1

#

)

| a ∈ A A.

Here T U A acts on V A by conjugation. With the given identifications, u ∈ U A acts on

a ∈ A as multiplication by u2 . Thus V A(2) as a Z[U A ]-module.

Proposition 3.19. Let n ≥ 1. Let A be a local integral domain with residue field k. If k is finite

of order p f we suppose that (p − 1) f > 2n.

The natural maps B → T and T → B induce isomorphisms on homology

Hn (T, Z) Hn (B, Z)

Proof. The Hochschild-Serre spectral sequence associated to the extension (4) takes the form

Ei,2 j = Hi (T, H j (V, Z)) = Hi (U A , H j (A(2), Z)) ⇒ Hi+ j (B, Z).

2

By Lemma 3.18, it follows that Ei,2 j = 0 if 0 < j ≤ n, and Ei,0

= Hi (T, Z) for all i.

Hence Hn (B, Z) = Hn (T, Z).

Remark 3.20. In particular, Hn (T, Z) Hn (B, Z) for all n ≤ 3 provided

|k| < {2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 16, 27, 32, 64}.

3.3. The complex L• . For a commutative ring A, we let Ln = Ln (A) := Z[Xn+1 ]. Equipped with

the boundary δn : Ln → Ln−1 this yields a complex, L• , of right GL2 (A)-modules. Restricting

the group action, this is also a complex of SL2 (A)-modules.

We now restrict attention to the case where A is a commutative local ring with residue field

k. We let π : A → k denote the canonical surjective quotient map. So U A = π−1 (k× ). More

generally, if X ∈ Mn (A) is an n × n matrix with coefficients in A, we let π(X) ∈ Mn (k) denote

the matrix obtained by applying π to each entry of X. Since A is a local ring X ∈ GLn (A) if and

only if π(X) ∈ GLn (k).

Similarly, u = (u1 , u2 ) ∈ U2 (A) if and only if π(u) ∈ U2 (k) = k2 \ {0} and ū ∈ X1 (A) if and only

if π(u) ∈ X1 (k) = P1 (k). Furthermore,

(u1 , . . . , un ) ∈ Ungen (A) ⇐⇒ (π(u1 ), . . . , π(un )) ∈ Ungen (k)

and hence

(ū1 , . . . , ūn ) ∈ Xn (A) ⇐⇒ (π(u1 ), . . . , π(un )) ∈ Xn (k).

Lemma 3.21. Hn (L• ) = 0 for 1 ≤ n < |k|.

14

KEVIN HUTCHINSON

Proof. When A = k is a field, the argument is given in [6], Lemma 4.4. This argument is easily

adapted to the current situation as follows:

For any subset S of P1 (k), let Dn (S ) denote the subgroup of Ln (A) generated by those (n + 1)tuples (ū1 , . . . , ūn+1 ) ∈ Xn+1 (A) which satisfy S ⊂ {π(u1 ), . . . , π(un+1 )}. Thus Dn (S ) = 0 if

|S | > n + 1. Furthermore, Dn (S 1 ∪ S 2 ) = Dn (S 1 ) ∩ Dn (S 2 ) for any S 1 , S 2 ⊂ P1 (k).

Now for each x ∈ P1 (k), choose u x ∈ U2 (A) satisfying π(u x ) = x and for n ≥ 0 define a

homomorphism S x : Ln → Ln+1 by

(

(ū x , ū1 , . . . , ūn+1 ), x < {π(u1 ), . . . , π(un+1 )}

S x (ū1 , . . . , ūn+1 ) =

0,

otherwise

Thus if (ū1 , . . . , ūn+1 ) ∈ Xn+1 (A) and if x < {π(u1 ), . . . , π(un+1 )} then

δS x (ū1 , . . . , ūn+1 ) = (ū1 , . . . , ūn+1 ) − S x δ(ū1 , . . . , ūn+1 ).

On the other hand, if x = π(u j ) for some j then

S x δ(ū1 , . . . , ūn+1 ) = (−1) j+1 (ū x , ū1 , . . . , ub̄j , . . . , ūn+1 ).

and hence

0 = δS x (ū1 , . . . , ūn+1 )

n

o

= (ū1 , . . . , ūn+1 ) − S x δ(ū1 , . . . , ūn+1 ) − S x δ(ū1 , . . . , ūn+1 ) − (−1) j (ū x , ū1 , . . . , uēj , . . . , ūn+1 ) .

In either case we have

δS x (ū1 , . . . , ūn+1 ) = (ū1 , . . . , ūn+1 ) − S x δ(ū1 , . . . , ūn+1 ) + w

where w ∈ Dn ({x}). Furthemore, if (ū1 , . . . , ūn+1 ) ∈ Dn (S ) for some subset S of P1 (k) then

w ∈ Dn (S ∪ {x}).

Suppose now that 1 ≤ n < |k| and that x1 , . . . , xn+2 are n + 2 distinct points of P1 (k). Let

z ∈ Ln (A) be a cycle. Then

(δS x1 − Id)z = S x1 δ(z) + z1 = z1

where z1 ∈ Dn ({x1 }) and z1 is again a cycle.

Thus (δS x2 − Id)z1 = z2 where z2 is a cycle belonging to Dn ({x1 , x2 }). Repeating the process we

get

(δS xn+2 − Id)(δS xn+1 − Id) · · · (δS x1 − Id)z ∈ Dn ({x1 , . . . , xn+2 }) = 0.

This equation has the form δ(y) + (−1)n+2 z = 0 and hence z = δ((−1)n+1 y) is a boundary as

required.

h i

3.4. H3 (SL2 (A), Z 12 ).

Theorem 3.22. Let A be a local integral domain with

field k satisfying |k| < {2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 16, 27, 32, 64}.

h residue

i

1

Then there is a natural short exact sequence of RA 2 -modules

h i

h i

h i

0 → tor(µA , µA ) 12 → H3 (SL2 (A), Z 12 ) → RB(A) 12 → 0.

Proof. In the case where A is a field, the proof can be found in [6, section 4]. We indicate here

the adaptions needed to extend that proof to the current context:

Associated to the complex L• = L• (A) there is hyperhomology spectral sequence of the form

h i

h i

E 1p,q = H p (SL2 (A), Lq 12 ) ⇒ H p+q (SL2 (A), L• 12 )

H3 of SL2 of local rings

15

and furthermore the augmentation L0 → Z induces an isomorphism

h i

h i

Hn (SL2 (A), L• 12 ) Hn (SL2 (A), Z 12 )

for n ≤ 3 by Remark 3.20.

The SL2 (A)-modules Ln are permutation modules, so the E 1 -terms are calculated using Shapiro’s

Lemma:

SL2 (A) acts transitively on X1 and the stabilizer of 0+ ∈ X1 is B = BA . Thus

2 (A)]

L0 = Z[X1 ] Z[B\SL2 (A)] IndZ[SL

Z

Z[B]

and hence

E 1p,0 = H p (SL2 (A), L0

h i

h i

1

1

)

H

(B,

Z

).

p

2

2

Similarly, SL2 (A) acts transitively on X2 and the stabilizer of (0+ , 0− ) is T = T A , so that

h i

h i

E 1p,1 = H p (SL2 (A), L1 12 ) H p (T, Z 12 ).

For n ≥ 3, the stabilizer in SL2 (A) of (ū1 , . . . , ūn ) ∈ Xn is Z(SL2 (A)) µ2 (A). By Corollary

3.10 it follows that for q ≥ 2 we have

h i

(

h i

RA 12 [Zq−2 ], p = 0

1

1

E p,q = RA 2 [Zq−2 ] ⊗ H p (µ2 (A), Z) =

0,

p>0

where Zn = Zn (A) as above.

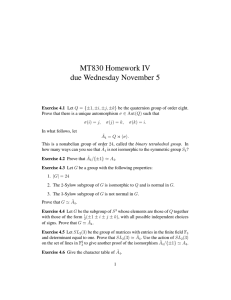

Thus our E 1 -page has the form

..

.

RA

h i

1

2

[Z2 ]

..

.

..

.

..

.

0

..

.

..

.

...

0

0

0

...

0

0

0

...

d1

RA

h

1

2

i

[Z1 ]

d1

RA

h

h

Z

h

Z

1

2

i

d1

1

2

i

d1

1

2

i

H1 (T, Z

h i

1

2

)

H2 (T, Z

d1

H1 (T, Z

h i

1

2

)

Now T U A . Thus E 1p,q H p (U A , Z

Now let

1

2

1

2

)

H3 (T, Z

d1

H2 (T, Z

h i

h i

h i

1

2

)

h i

1

2

)

...

h i

)

...

d1

H3 (T, Z

) for p ≤ 3 and q ∈ {0, 1}.

"

#

0 −1

w :=

∈ SL2 (A).

1 0

Then w(0+ ) = 0− and w(0− ) = 0+ . It follows easily that the differential

h i

h i

d1 : E 1p,1 = H p (T, Z 12 ) → H p (T, Z 21 ) = E 1p,0

1

2

16

KEVIN HUTCHINSON

is the map

H p (T, Z

h i

1

2

)

w p −1

/

H p (T, Z

h i

1

2

)

h i

h i

1

1

)

→

H

(T,

Z

) is the map induced by conjugation by w. However,

p

2

2

h i

h i

1

1

conjugating by w is just the inversion map on U A T . Thus d1 : Z 21 = E0,1

→ E0,0

= Z 21

h i

h i

1

1

→ E1,0

= U A 12 is the map u 7→ u−2 and hence is an

is the zero map. d1 : U A 12 = E1,1

h i

h i

1

1

isomorphism. d1 : ∧2Z (U A 21 ) = E2,1

→ E2,0

= ∧2Z (U A 21 ) is the zero map.

h i

h i

h i

1

1

1

1

→ E3,0

Finally, E3,1

= E3,0

= H3 (U A , Z 12 ) ∧3Z (U A 21 ) ⊕ tor(µA , µA ) 12 . The map d1 : E3,1

is an isomorphism of the first factor and the zero map on the second factor.

The differential

h i

h i

1

1

d1 : RA 12 H0 (SL2 (A), L2 ) = E0,2

→ E0,1

= H0 (SL2 (A), L1 ) Z 21

where w p : H p (T, Z

is the natural augmentation sending hui to 1 for any u ∈ U A .

As in the proof of [6, Theorem 4.3], the differential

h i

h i

1

1

d1 : RA 12 [Z1 ] H0 (SL2 (A), L3 ) = E0,3

→ E0,2

= H0 (SL2 (A), L2 ) RA 12

is the RA -homomorphism sending (z) to hhzii hh1 − zii ∈ I2A for any z ∈ WA .

By the proof of Proposition 3.11 above, the differential

h i

h i

1

1

→ E0,3

= H0 (SL2 (A), L3 ) RA 12 [Z1 ]

d1 : RA 21 [Z2 ] H0 (SL2 (A), L4 ) = E0,4

is the map

! D

!

!

E 1 − z−1

1 − z1

z2

1

−1

(z1 , z2 ) 7→ h1 − z1 i

− z1 − 1

+ hz1 i

− (z2 ) + (z1 )

1 − z2

z

1 − z−1

1

2

Thus the E 2 -page of our spectral sequence has the form

0

0

..

.

0

0

..

.

0

0

∧2Z (U A

h i

1

)

2

h i

0

∧2Z (U A

h i

1

)

2

RP1 (A)

IA

h i

1

2

Z

h i

/JA

1

2

1

2

h i

1

2

..

.

tor(µA , µA )

h i

1

2

where JA ⊂ RA is the ideal generated by the Steinberg elements hhuii hh1 − uii.

H3 of SL2 of local rings

17

Clearly there are no nonzero d2 -differentials. So the E 3 -page has the form

3

E0,4

RP1 (A)

h i

1

2

0

0

..

.

0

0

..

.

0

..

.

d3

IA

h i

1

2

/JA

h i

1

2

0

d3

0

..

.

h i

1

)

2

0

∧2Z (U A

0

∧2Z (U A 12

h i

Z

1

2

h i

)

tor(µA , µA )

h i

1

2

The argument nowh concludes

exactly as in [6, section 4]: The cokernel of the differential

i

1

3

3

2

4

∞

d : E0,4 → ∧Z (U A 2 ) is annihilated by 2 and hence E2,1

= E2,1

= 0. There is a commutative

diagram

h i d3

h i

/ ∧2 (U A 1 )

RP1 (A) 12

Z

2

λ2

P(A)

h i

1

2

λ

4

∞

It follows that E0,3

= E0,3

= Ker(λ2 : RP1 (A)

the proof of the theorem.

/

&

S2Z (U A

h i

1

2

h i

1

)

2

→ S2Z (U A )

h i

h i

1

1

)

=

RB(A)

. This completes

2

2

3.5. Local integral domains with infinite residue field. We will require the following two

results of B. Mirzaii:

Proposition 3.23. ([15, Corollary 5.4],[16, Theorem 3.7]) Let R be a ring with many units.

(1) If R is an integral domain, there is a natural short exact sequence

h i

h i

h i

0 → tor(µR , µR ) 12 → H3 (SL2 (R), Z 12 )GR → B(R) 12 → 0.

(2) There is a natural isomorphism

h i

h i

h i

H3 (SL2 (R), Z 12 ) = H3 (SL2 (R), Z 12 )GR K3ind (R) 21 .

UA

Remark 3.24. A local ring with infinite residue field is an example of a ring with many units.

We note the following immediate corollary to Mirzaii’s results:

Corollary 3.25. Let A be a discrete valuation ring with field of fractions K

h iand infiniteh residue

i

field F. Suppose that char(F) = char(K). Then the functorial map B(A) 12 → B(K) 12 is an

isomorphism.

18

KEVIN HUTCHINSON

Proof. By Theorem 2.1 the natural map K3ind (A) → K3ind (K) is an isomorphism. Thus there is a

commutative diagram with exact rows

h i

h i

h i

/ tor(µA , µA ) 1

/ H3 (SL2 (A), Z 1 )G

/ B(A) 1

/0

0

A

2

2

2

/

0

tor(µK , µK )

/

h i

1

2

/

h i

K3ind (K) 12

B(K)

h i

1

2

/

0

from which the result immediately follows.

Combining Mirzaii’s results with Theorem 3.22 gives:

Corollary 3.26. Let A be a local integral domain with infinite residue field. Then there is a

natural short exact sequence

h i

h i

h i

0 → RB0 (A) 21 → H3 (SL2 (R), Z 12 ) → K3ind (A) 12 → 0

and

RB0 (A)

h i

1

2

IA RB(A)

h i

1

2

IA H3 (SL2 (R), Z

h i

1

).

2

Proof. Combining Theorem 3.22 with the statements in Proposition 3.23 we obtain a commutative diagram with exact rows and columns

0

0

IA H3 (SL2 (A), Z

0

0

/

/

tor(µA , µA )

h i

1

2

/

tor(µA , µA )

1

2

1

2

)

h i

H3 (SL2 (A), Z 12 )

=

h i

h i

/

h i

K3ind (A) 21

0

from which the statements of this corollary immediately follow.

/

/

RB0 (A)

h i

1

2

RB(A)

/

1

2

B(A)

/

h i

h i

1

2

/

0

0

0

Corollary 3.27. Let A be a local integral domain with infinite residue field. Suppose that

U A = U A2 . Then

h i

h i

h i

RB0 (A) 21 = 0 and RB(A) 12 B(A) 21 .

4. Submodules of RP(A)

In this section, A will denote a commutative local ring, with maximal ideal M and residue field

k = A/M. Furthermore, we will suppose that k has at least four elements.

In this case, we have U A = A \ M and WA = U A \ U1 , where U1 = U1,A = 1 + M. In particular,

if x ∈ U A , then x ∈ WA ⇐⇒ x−1 ∈ WA .

H3 of SL2 of local rings

19

4.1. The modules KA(i) . As in [8], we define two families of elements of RP(A).

Given x ∈ WA we define

h i

ψ1 (x) := [x] + h−1i x−1

and

h i D

E

h i

ψ2 (x) := h1 − xi hxi [x] + x−1 = x−1 − 1 [x] + h1 − xi x−1 .

Observe, from the definitions, that ψi x−1 = h−1i ψi (x) for all x ∈ WA .

Lemma 4.1. For i = 1, 2 we have

(1) ψi (xy) = hxi

ψi (y) + ψi (x) whenever x, y, xy ∈ WA .

−1

(2) hxi ψi x + ψi (x) = 0 for all x ∈ WA .

Proof.

(1) The proof of Lemma 3.1 in [8] adapts without alteration.

(2) Let x ∈ WA . Choose y ∈ WA such that xy ∈ WA also. (Note that this is possible

because of the hypothesis that |k| ≥ 4.)

Then by part (1) we have

ψi (xy) = hyi ψi (x) + ψi (y) =⇒ hyi ψi (x) = ψi (xy) − ψi (y)

and

ψi (y) = ψi xy · x−1 = hxyi ψi x−1 + ψi (xy) =⇒ hxyi ψi x−1 = ψi (y) − ψi (xy) .

Form these we deduce that

hyi ψi (x) = − hxyi ψi x−1 .

Multiplying both sides of this equation by hyi gives the result.

Lemma 4.2. Let u ∈ U1 . For any w1 , w2 ∈ WA , we have

ψi (w1 u) − hui ψi (w1 ) = ψi (w2 u) − hui ψi (w2 )

for i = 1, 2.

Proof. First suppose that w1 . w2 (mod U1 ). Then w1 w−1

2 ∈ WA and hence

ψi (w1 u) = ψi (w−1

2 w1 ) · (w2 u)

= hw2 ui ψi w1 w−1

+ ψi (w2 u)

2

= hui hw2 i ψi w1 w−1

+ ψi (w2 u)

2

= hui (ψi (w2 ) − ψi (w1 )) + ψi (w2 u)

giving the result in this case.

On the other hand, if w1 ≡ w2 (mod U1 ) choose w3 ∈ WA with w3 . w1 (mod U1 ). Then

ψi (w1 u) − hui ψi (w1 ) = ψi (w3 u) − hui ψi (w3 ) ψi (w2 u) − hui ψi (w2 ) .

We now extend the definition of ψi (x) to allow x ∈ U1 . For u ∈ U1 , we define

ψi (u) := ψi (uw) − hui ψi (w)

for any w ∈ WA .

20

KEVIN HUTCHINSON

Proposition 4.3. For i = 1, 2 the maps U A → RP(A), x 7→ ψi (x) define 1-cocycles; i.e. we have

ψi (xy) = hxi ψi (y) + ψi (x)

for all x, y ∈ U A .

Proof. If x, y, xy ∈ WA , this is part (1) of Lemma 4.1.

If x, y ∈ WA , but xy ∈ U1 , then

ψi (xy) = ψi xy · y−1 − hxyi ψi y−1

= ψi (x) − hxi hyi ψi y−1

= ψi (x) + hxi ψi (y)

using Lemma 4.1 (2) in the last step.

If x ∈ U1 and y ∈ WA , the identity is just the definition of ψi (x).

On the other hand, if x ∈ WA and y ∈ U1 , then choose w ∈ WA such that xw ∈ WA . We have

hxi ψi (y) + ψi (x) =

=

=

=

hxi (ψi (wy) − hyi ψi (w)) + ψi (x)

hxi ψi (wy) + ψi (x) − hxyi ψi (w)

ψi (xyw) − hxi ψi (yw)

ψi (xy) .

Finally, suppose that x, y ∈ U1 . Let w ∈ WA . Then

ψi (xy) =

=

=

=

ψi (xyw) − hxyi ψi (w)

hxi ψi (yw) + ψi (x) − hxyi ψi (w)

hxi (ψi (yw) − hyi ψi (w)) + ψi (x)

hxi ψi (y) + ψi (x)

as required.

We recall here, from [8] some of the basic algebraic properties of the ψi (x). (The proofs given

in [8] for the case of fields adapt without change to the case of local rings.)

Proposition 4.4. For i ∈ {1, 2} we have:

(1) hhxii

ψi (y) = hhyii ψi (x)

for

all x, y

(2) ψi xy2 = ψi (x) + ψi y2 for all x, y

(3) hhxii ψi y2 = 0 for all x, y

(4) 2 · ψi (−1)

= 0 for all i

2

(5) ψi x = − hhxii ψi (−1) for all x

(6) 2 · ψi x2 = 0 for all x and if −1 is a square in U A then ψi x2 = 0 for all x.

(7) hhxii hhyii ψi (−1) = 0 for all x, y

(8) h−1i hhxii ψi (y) = hhxii ψi (y) for all x, y

(9) Let

(

1, −1 ∈ U A2

(A) :=

2, −1 < U A2

The map U A /U A2 → RP(A), hxi 7→ (A)ψi (x) is a well-defined 1-cocycle.

Corollary 4.5. For i = 1, 2 and a ∈ U A

ψi (a) − ψi −a−1 = ψi (−1) .

H3 of SL2 of local rings

21

Proof. For a ∈ U A , since h−1i ψi a−1 = ψi (a) we have

ψi −a−1 = ψi −1 · a−1 = h−1i ψi a−1 + ψi (−1) = ψi (a) + ψi (−1) .

Lemma 4.6. For i = 1, 2 and for all x ∈ U A

2

(1) λ1 (ψi (x)) = −p−1

+ hhxii = hh−xii hhxii ∈ IA

2

(2) λ2 (ψi (x)) = (−x) ◦ x ∈ SZ (U A ).

(1) For x ∈ WA , this is a straightforward calculation given in [8, Lemma 3.3]. For

x ∈ U1 it follows from the identity hhxwii − hxi hhwii = hhxii in RA .

(2) Since U A acts trivially on S2Z (U A ), we have for any x ∈ WA

h i

λ2 (ψ1 (x)) = λ2 (ψ2 (x)) = λ2 ([x]) + λ2 ( x−1 )

Proof.

= (1 − x) ◦ x + (1 − x−1 ) ◦ x−1

!

1−x

= (1 − x) ◦ x −

◦x

−x

= (−x) ◦ x.

On the other hand, if x ∈ U1 , the result follows from the identity

(−xw) ◦ (xw) − (−w) ◦ w = (−x) ◦ x

in S2Z (U A ).

Let KA(i) denote the RA -submodule of RP(A) generated by the set {ψi (x) | x ∈ U A }.

Lemma 4.7. Then for i ∈ {1, 2}

2

λ1 KA(i) = p−1

+ (IA ) ⊂ IA

and Ker(λ1 |K (i) ) is annihilated by 4.

A

Proof. The first statement follows from Lemma 4.6

For the second, the proof of Lemma 3.3 in [8] applies without change.

Let

g

RP(A)

:= RP(A)/KA(1)

Then the RA -homomorphism

g

e : RP(A)

Λ

→

I2A ⊕ S2Z (U A )

Λ(KA(1) )

g

e

is well-defined and we set RB(A)

:= Ker(Λ).

g

Corollary 4.8. The natural map RB(A) → RB(A)

is surjective with kernel annihilated by 4. In

particular,

h i

h i

1

g

RB(A) 1 = RB(A)

.

2

2

22

KEVIN HUTCHINSON

Proof. From the definitions,

g

RB(A)

RB(A)

RB(A) ∩ KA(1)

and

RB(A) ∩ KA(1) = Ker(Λ|K (1) ) ⊂ Ker(λ1 |K (1) )

A

A

which is annihilated by 4.

4.2. The constant DA . In [23], Suslin shows that, for an infinite field F, the elements [x] +

[1 − x] ∈ B(F) ⊂ P(F) are independent of x and that the resulting constant, C̃ F , has order

dividing 6. Furthermore Suslin shows that C̃R has exact order 6.

In [8, Lemma 3.5] it is shown that the elements

C(x) = [x] + h−1i [1 − x] + hh1 − xii ψ1 (x) ∈ RB(F)

are constant (for a field with at least 4 elements) and have order dividing 6. In fact the proof

given there extends without alteration to the case of local rings:

Lemma 4.9. Let A be a local ring whose residue field has at least 4 elements. For all a, b ∈ WA

C(a) := [a] + h−1i [1 − a] + hh1 − aii ψ1 (a) ∈ RB(A) and C(a) = C(b).

We denote this constant by C A and we set DA := 2C A . Of course, C A maps to C̃ A under the

natural map RP(A) → P(A). Similarly, we denote the image of DA in P(A) by D̃A . Thus, of

course, D̃A = 2C̃ A in P(A). In fact, these elements lie in B(A) by Lemma 4.9.

Let Φ(X) denote the polynomial X 2 − X + 1 ∈ A[X].

Lemma 4.10. Let A be a local ring whose residue field has at least 4 elements.

(1) 3C A = ψ1 (−1) and 6C A = 0.

(2) If Φ(X) has a root in A then DA = 0 and C A = ψ1 (−1).

Proof.

(1) Let a ∈ WA . Then

3C A =

=

+

+

=

+

=

=

=

!

1

C(a) + C(1 − a ) + C

1−a

**

++

1

[a] + h−1i [1 − a] +

ψ1 (a)

1−a

h

i

h i

1 − a−1 + h−1i a−1 + hhaii ψ1 1 − a−1

"

# DD

#

"

!

EE

1

1

1

−1

+ 1−a

ψ1

+ h−1i

1−a

1 − a−1

1−a

!

1

ψ1 (a) + ψ1 1 − a−1 + ψ1

1−a

**

++

!

DD

EE

1

1

−1

−1

ψ1 (a) + hhaii ψ1 1 − a + 1 − a

ψ1

1−a

1−a

*

+

!

D

E

1

1

−1

−1

ψ1 (a) + hai ψ1 1 − a + 1 − a ψ1

1−a

1−a

!

!

!

1

1

1

ψ1 −1

− ψ1

+ ψ1 (a − 1) − ψ1 (a) + ψ1 − − ψ1 1 − a−1

a −1

1−a

a

3ψ1 (−1) = ψ1 (−1)

−1

H3 of SL2 of local rings

23

since for any b, we have

!

1

ψ1 (b) − ψ1 − = ψ1 (−1)

b

by Corollary 4.5.

(2) Let a ∈ A with Φ(a) = 0. Then 1 − a = a−1 and a ∈ WA . Furthermore, from 0 =

(a + 1)Φ(a) it follows

that a3 = −1 and hence a = −b2 where b = a2 . Thus ψ1 (a) =

ψ1 (−1) + ψ1 b2 and hence 2ψ1 (a) = 0. But

C A = [a] + h−1i [1 − a] − hh1 − aii ψ1 (1 − a)−1 = ψ1 (a) − hhaii ψ1 (a) = − hai ψ1 (a)

and hence 0 = 2C A = DA . Thus also C A = 3C A = ψ1 (−1).

From [8] we also have the following identification of the element DA :

Lemma 4.11. For any a ∈ WA we have

"

#

!

1

1

− ψ1

.

DA = [a] + h−1i

1 − a−1

1−a

Proposition 4.12. For a field F we have DF = 0 if and only if Φ(X) has a root in F.

Proof. The ‘if’ statement is established by Lemma 4.10 (2).

Now if char(F) = 3 then −1 is a root of X 2 − X + 1 and hence DF = 0.

So we may assume that char(F) , 3. Thus X 2 − X + 1 has a root in F if and only if F contains a

primitive cube root of unity, ζ3 . Let k be the prime subfield of F. If k = Q, then D̃k = D̃Q ∈ B(Q)

has order 3 (since Q embeds in R). On the other hand, if k = F p then D̃k has order 3 if and only

if p ≡ −1 (mod 3) by [6] Lemma 7.11. Thus, in all cases, D̃k = 0 in B(k) if and only if ζ3 ∈ k.

By Suslin’s Theorem ([23] Theorem 5.2) – or by [6, Corollary 7.5] when k is finite – we have

a commutative diagram with exact rows

/

0

/

TorZ1]

(µk , µk )

0

/

TorZ1]

(µF , µF )

/

/

K3ind (k)

_

K3ind (F)

/

/

B(k)

B(F)

/

0

0

where the middle vertical arrow is injective ([12], Corollary 4.6). If D̃k , 0, then it lies in the

kernel of B(k) → B(F) only if 3|µF . Thus D̃F = 0 only if ζ3 ∈ F.

Corollary 4.13. For any field F, DF = 0 if and only if D̃F = 0, and the map RB(F) → B(F)

induces an isomorphism Z · DF Z · D̃F .

2

Corollary 4.14. Let A be a local ring with residue field k. Suppose either that U1,A = U1,A

and that char(k) , 2, 3 or that char(k) = 2 and A is henselian. Then the functorial map

RB(A) → RB(k) induces an isomorphism Z · DA Z · Dk .

Proof. Clearly DA = 0 =⇒ Dk = 0.

Conversely, if Dk = 0 then Φ(X) has a root in k . The hypotheses then imply that Φ(X) has a

root in A and thus DA = 0 also.

Remark 4.15. When char(k) = 3, the result may fail. For example, Φ(X) has no root in Q3 , so

that DQ3 , 0, and hence DZ3 , 0 also. But DF3 = 0.

24

KEVIN HUTCHINSON

4.3. A key identity. The purpose of this section is to prove the important identity hhaii DA =

ψ1 (a) − ψ2 (a) in RP(A) for all a ∈ U A (Theorem 4.19 below). This identity was proved in the

case when A is a field in [8].

Let t denote the matrix of order 3

"

#

−1 −1

∈ SL2 (Z).

1 0

It can be shown that H3 (SL2 (Z), Z) is cyclic of order 12 and that the inclusion G := hti → SL2 (Z)

induces an isomorphism H3 (G, Z) H3 (SL2 (Z), Z)[3].

We will identify A with A+ = ι+ (A) ⊂ X1 .

For any subset S of A, we have S n ⊂ X1n and we let

∆(n, S ) := S n ∩ Xn = {(s1 , . . . , sn ) ∈ S n | si − s j ∈ U A for i , j}.

Thus there is a natural inclusion of additive groups Z[∆(n, S )] → Z[Xn ].

We note that WA is a right G-set since for any a ∈ WA

"

#

−1 −1

a · t = [a, 1] ·

= [1 − a, −a] = [1 − a−1 , 1] = 1 − a−1 ∈ WA ⊂ X1 .

1 0

For a local ring A, let W̃A := WA \ {a ∈ A| Φ(π(a)) = 0 in k}.

Lemma 4.16. If x ∈ W̃A , then x · ti − x · t j ∈ U A whenever i . j (mod 3).

Proof. If x ∈ W̃A , then x, 1 − x, Φ(x) ∈ U A . The statement thus follows from the identities

1 Φ(x)

=

x

x

Φ(x)

1

=

= x−

1−x x−1

1

1

Φ(x)

= 1− −

=

.

x 1 − x x(x − 1)

x−x·t = x−1+

x − x · t2

x · t − x · t2

Lemma 4.17. Let A be a local ring whose residue field, k, has at least 10 elements. Let

Ln = Ln (A) = Z[Xn+1 ] as above. Let F• be the (right) homogeneous standard resolution of

Z over Z[G]. Then an augmentation-preserving chain map of right Z[G]-modules F• → L• in

dimensions three and below can be constructed as follows:

Let x ∈ W̃A and let y ∈ W̃A with

π(y) < {π(x), π(x) · t, π(x) · t2 } ⊂ k.

Then define βnx,y : Fn → Ln as follows:

Given g ∈ G, let β0x,y (g) = x · g ∈ A ⊂ X1 .

Given g0 , g1 ∈ G let

(

(x · g0 , x · g1 ), g0 , g1

x,y

β1 (g0 , g1 ) =

0,

g0 = g1

H3 of SL2 of local rings

25

Given g0 , g1 , g2 ∈ G, let

x,y

β2 (g0 , g1 , g2 ) =

(x · g0 , x · g1 , x · g2 ),

if g0 , g1 , g2 are distinct

0,

g0 = g1 or g1 = g2

(y · g0 , x · g0 , x · g1 )

+(y · g0 , x · g1 , x · g0 ), if g0 = g2 , g1

Given g0 , g1 , g2 , g3 ∈ G let

x,y

β3 (g0 , g1 , g2 , g3 ) =

gi = gi+1 for some 0 ≤ i ≤ 2

0,

(y · g0 , y · g1 , x · g0 , x · g1 )

+(y · g0 , y · g1 , x · g1 , x · g0 ),

(x · g0 , y · g0 , x · g1 , x · g2 )

+(x · g0 , y · g1 , x · g2 , x · g1 ),

(y · g0 , x · g0 , x · g1 , x · g3 )

−(y · g0 , x · g1 , x · g0 , x · g3 ),

(y · g0 , x · g1 , x · g2 , x · g0 )

−(y · g0 , x · g0 , x · g1 , x · g2 ),

if g0 = g2 , g1 and g1 = g3

if g1 = g3 and

g0 , g1 , g2 are distinct

if g0 = g2 and

g0 , g1 , g3 are distinct

if g0 = g3 and

g0 , g1 , g2 are distinct

Proof. By Lemma 4.16, the image of βnx,y lies in Z[∆(n, A)] ⊂ Z[Xn+1 ]. It is a straightforward

computation to verify that this map is an augmentation-preserving chain map.

Corollary 4.18. Let x, y be chosen as in Lemma 4.17. Let

C := C(x, y) = cr(y, x · t, x · t2 , x) − cr(y, x, x · t, x · t2 ) + cr(y, y · t, x, x · t) + cr(y, y · t, x · t, x) ∈ RP(A).

Then C is independent of the choice of x, y, C ∈ RB(A) and 3C = 0.

Proof. Let K → SL2 (A) be any group homomorphism. Then there is a hypercohomolgy spectral

sequence

E 1p,q (K) = H p (K, Lq ) =⇒ H p+q (K, L• )

and H p+q (K, L• ) = H p+q (K, Z) when p + q is not too large. There are associated edge homomorphisms giving a commutative diagram

/

Hn (K, Z)

2

E0,n

(K) = Hn ((L• )K )

αn (K)

Hn (SL2 (A), Z)

/

*

2

E0,n

(SL2 (A))

= Hn ((L• )SL2 (A) )

The map αn (K) can be constructed as follows: Let F• (K) be a projective right Z[K]-resolution

of Z and let β• : F• (K) → L• be any augmentation-preserving homomorphism of right Z[k]complexes. Then αn (K) is the induced map on nth homology groups associated to the map of

complexes F• (K) ⊗Z[k] Z → L• ⊗Z[SL2 (A)] Z. The map αn (K) is independent of the choices of

resolution F• (K) and chain map β• .

Applying this to G, F• and β3x,y as in Lemma 4.17, and observing that the cycle (1, t, t, t2 ) +

(1, t, t2 , 1) + (1, t, 1, t) ∈ F3 represents a generator of H3 (G, Z) Z/3, we see that the map

α3 : Z/3 = H3 (G, Z) → H3 ((L• )SL2 (A) ) sends 1 to the class of

(y, x · t, x · t2 , x) − (y, x, x · t, x · t2 ) + (y, y · t, x, x · t) + (y, y · t, x · t, x) ∈ L3

But the proof of Theorem 3.22 shows that H3 ((L• )SL2 (A) ) RP1 (A) and that this isomorphism

is induced by the refined cross ratio map.

Thus 1 ∈ Z/3 maps to C = C(x, y) ∈ RP1 (A) under α3 . It follows that C is independent of x, y

and that 3C = 0.

26

KEVIN HUTCHINSON

h i

Finally, the proof of Theorem 3.22 shows that, at least after tensoring with Z 12 , the image of

h i

∞

= RB(A) 12 . Since 3C = 0, it follows that C ∈ RB(A). the edge homomorphism lies in E0,3

Theorem 4.19. Let A be a local ring whose residue field has at least 10 elements. Then

(1) For all x ∈ U A , hhxii DA = ψ1 (x) − ψ2 (x).

(2) hhxii DA = 0 if x ∈ U A is of the form ±Φ(a)u2 for some a, u ∈ U A .

Proof. Choose x, y ∈ W̃A as in Lemma 4.17. Then, the calculations in the proof of Theorem

3.12 of [8] show that

C = C(x, y) = h−Φ(x)ri (ψ2 (r) − ψ1 (r) − DA )

where

x−y

∈ WA .

x − 1 − xy

By the Corollary, C has order 3 and is independent of x and y. Now, by choice of x and y, r can

2

assume any value in WA . In particular,

we can arrange for r to have the form −u for some unit

u. Since 4C = 4DA = 0 and 2ψi −u2 = 0 for i = 1, 2, multiplying by 4 gives

r = r(x, y) =

C = − hΦ(x)i DA

for any x ∈ W̃A .

Given x ∈ W̃A we can find x0 ∈ W̃A such that xx0 − 1, x + x0 − 1 ∈ U A and

xx0 − 1

x00 :=

∈ W̃A .

x + x0 − 1

Since Φ(x)Φ(x0 ) = Φ(x00 ) · (x + x0 − 1)2 , we have

C = − hΦ(x00 )i DA = − hΦ(x)i hΦ(x0 )i DA = hΦ(x)i C

for any x ∈ W̃A , and hence C = −DA .

It follows that hΦ(x)i DA = DA for any x ∈ W̃A ; i.e hhΦ(x)ii DA = 0 for all x ∈ W̃A . Since

h−1i DA = DA also, it follows that

DD

EE

±Φ(x)u2 DA = 0

for all x ∈ W̃A and u ∈ U A .

We now have that

−DA = C = h−Φ(x)ri (ψ2 (r) − ψ1 (r) − DA )

for all r ∈ WA and some x ∈ W̃A . Thus

− hΦ(x)ri DA = ψ2 (r) − ψ1 (r) − DA =⇒ hhrii DA = ψ1 (r) − ψ2 (r)

since hΦxi DA = DA . It follows that

hhrii DA = ψ1 (r) − ψ2 (r)

for all r ∈ WA .

Finally, let x ∈ U1,A = U A \ WA . Fix r ∈ WA . Then ψi (x) = ψi (rx) − hxi ψi (r) for i = 1, 2.

Furthermore, hhxii = hhrxii − hxi hhrii. It follows that

hhxii DA = hhrxii DA − hxi hhrii DA

= ψ1 (rx) − ψ2 (rx) − hxi ψ1 (r) + hxi ψ2 (r)

= ψ1 (x) − ψ2 (x)

as required.

H3 of SL2 of local rings

27

Corollary 4.20. Let A be a local ring whose residue field has at least 10 elements. For all

a ∈ UA

hhaii C A = ψ2 (a) − ψ1 a−1 .

Proof. Since 3C A = ψ1 (−1) and 2C A = DA , we have C A = ψ1 (−1) − DA .

Thus, if a ∈ U A we have

hhaii C A = hhaii ψ1 (−1) − hhaii DA = hhaii ψ1 (−1) − hh−aii DA

since hh−1ii DA = 0. Thus, by Theorem 4.19

hhaii C A = hhaii ψ1 (−1) − ψ1 (−a) + ψ2 (−a)

= hai ψ1 (−1) − ψ1 (−1) − hai ψ1 (−1) − ψ1 (a) + ψ2 (−a)

= −(ψ1 (−1) + ψ1 (a)) + ψ2 (−a)

= −(ψ1 (−1) + h−1i ψ1 a−1 ) + ψ2 (−a)

= ψ2 (−a) − ψ1 −a−1 .

However, hh−1ii C A = 0. Thus hhaii C A = hh−aii C A = ψ2 (a) − ψ1 a−1 .

4.4. The module DA . We let DA denote the cyclic RA -submodule of RB(A) generated by DA .

Of course, since 3DA = 0 always, in fact DF is a module over the group ring F3 [GA ].

Let NA be the subgroup of U A generated by elements of the form ±Φ(x)u2 , x ∈ W̃A , u ∈ U A .

By Theorem 4.19 (2), we have hxi DA = DA if a ∈ NA . Let GA = U A /NF . Thus the action

of GA on DA factors through the quotient GA , and hence DA is a cyclic module over the ring

cA := F3 [GA ].

R

Remark 4.21. The results of section 6 below (see Corollary 6.45) show that if F is a highercF . In

dimensional local field, satisfying certain conditions, then DF is a free of rank one over R

this case it follows that we have a converse to (2) of Theorem 4.19: hhxii DF = 0 if and only

x ∈ NF . (And hence, over such fields, ψ1 (x) = ψ2 (x) if and only if x ∈ NF .)

Lemma 4.22. Let A be a local ring with residue field F. Then the natural map DA → DF is

surjective.

cF -module, then DA DF .

Furthermore, if U1,A = U 2 and if DF is free (of rank 1) as a R

1,A

Proof. Since GA maps onto GF and hence RA maps onto RF the first statement is clear.

For the second statement, note that the conditions ensure that GA GF and under this isomorcA R

cF and the composite map

phism, NA corresponds to NF . Thus R

cA

R

is an isomorphism.

//

DA

/

DF

4.5. Reduced Bloch Groups. We introduce some quotient groups of (pre-)Bloch groups which

will be required in our computations below.

First recall that

RP(A)

g

g

g

e ⊂ RP(A).

RP(A)

=

and RB(A)

= Ker(Λ)

KA(1)

28

KEVIN HUTCHINSON

g

Furthermore (4.8) the map RB(A) → RB(A)

is surjective with kernel annihilated by 4. Since

DA is annihilated by 3, it follows that the composite

g

DA → RB(A) → RB(A)

g

is injective and we will identify DA with its image in RB(A).

We further define and

RP(A) :=

g

RP(A)

RP(A)

= (1)

DA

KA + DA

and

RB(A) :=

g

RB(A)

.

DA

Corollary 4.8 implies:

Lemma 4.23. For any field or local ring A there is a short exact sequence

h i

h i

0 → DA → RB(A) 21 → RB(A) 12 → 0.

Observe also that KA(2) ⊂ KA(1) + DA by Theorem 4.19 (2). It follows that for i = 1, 2 and all

x ∈ U A we have ψi (x) = 0 in RP(A).

Lemma 4.24. Let A be a local ring.

h i

(1) For all x ∈ WA , x−1 = − h−1i [x] = − hxi [x] in RP(A).

(2) For all x ∈ WA , hhyii [x] = 0 in RP(A)h whenever

y ≡ −x (mod U A2 ).

i

(3) For all x ∈ WA , [1 − x] = h−1i [x] = x−1 in RP(A).

Proof.

(1) The first equality follows from ψ1 (x) = 0, the second from ψ2 (x) = 0.

(2) From hxi [x] = h−1i [x] it follows that hyi [x] = h−xi [x] = [x].

(3) Since 2C A = DA and 3C A = ψ1 (−1) ∈ KA(1) , it follows that C A = 0 in RP(A), and thus

we have (from the definition of C A ) that 0 = [x] + h−1i [1 − x] in RP(A).

g 1 (A). Let A be a commutative local ring or a field.

4.6. The module RP

2

f

Recall that, for any x ∈ U A , λ1 (ψ1 (x)) = −p−1

+ hhxii = hh−xii hhxii ∈ IA ⊂ RA . Let RA :=

−1

−1

RA /p+ RA . If denotes the augmentation homomorphism RA → Z, then (p+ ) = 2 and thus

−1

−1

2

p−1

+ R A ∩ I A = p+ R A ∩ I A = p+ I A .

Therefore:

Lemma 4.25. The inclusion map I2A → RA induces an injective map of RA -modules I2A /p−1

+ IA →

f

RA .

Let λ̃1 denote the composite map

g

RP(A)

→

I2A

fA ,

→R

p−1

I

A

+

[x] 7→ hh1 − xii hhxii

g 1 (A) := Ker(λ̃1 ).

and let RP

Let S̃2Z (U A ) denote the quotient of the abelian group S2Z (U A ) modulo the subgroup, QA say,

generated by the elements x ◦ −x, x ∈ U A . Observe that QA = λ2 (KA(1) ).

H3 of SL2 of local rings

29

g

Lemma 4.26. RB(A)

= Ker(λ̃2 ) where λ̃2 is the restriction of the map

g

RP(A)

→ S̃2Z (U A ),

[x] 7→ (1 − x) ◦ x

g 1 (A)

to RP

g

g

Proof. Let α̃ = α + KA(1) ∈ RP(A).

Then, by definition, α̃ ∈ RB(A)

if and only if there exists

(1)

β ∈ KA such that λi (α) = λi (β) for i = 1, 2. On the other hand, α̃ ∈ Ker(λ̃2 ) if and only if there

exist β1 , β2 ∈ KA(1) with λi (α) = λi (βi ) for i = 1, 2.

g

Thus RB(A)

⊂ Ker(λ̃2 ), and to prove the converse inclusion, it’s enough to prove that if α ∈

RP(A) and βi ∈ KA(1) for i = 1, 2 such that λi (βi ) = λi (α) for i = 1, 2, then λ2 (α) = λ2 (β1 ) also.

To see this we recall that there are natural homomorphisms of abelian groups

p1 : I2A → Sym2Z (GA ),

hhaii hhbii 7→ hai ∗ hbi

and

p2 : S2Z (U A ) → Sym2Z (GA ), a ◦ b 7→ hai ∗ hbi

satisfying p1 ◦ λ1 = p2 ◦ λ2 (see [6] for more details).

Furthermore, let τ : U A → QA be the map x 7→ (−x) ◦ x. It is easily verified that τ is a group

homomorphism containing −1 and (U A )2 in its kernel. Thus τ induces a group homomorphism

τ̄ : U A / ± (U A )2 → QA ,

x 7→ (−x) ◦ x.

Composing this with p2 gives the map

U A / ± (U A )2 → Sym2Z (GA ) = Sym2F2 (GA ),

x 7→ h−1i ∗ hxi + hxi ∗ hxi

which is clearly injective. It follows that τ̄ is an isomorphism and that the restriction of p2 to

QA is injective.

But λ2 (α) ∈ λ2 (KA(1) ) = QA and

p2 (λ2 (α)) = p1 (λ1 (β1 )) = p2 (λ2 (β1 ))

so that λ2 (α) = λ2 (β1 ) as required.

h i

e

Let P(A)

denote P(A) modulo the subgroup generated by the elements [x] + x−1 (of order 2).

e denote the kernel of the map P(A)

e

Let B(A)

→ S̃2Z (U A ), [x] 7→ (1 − x) ◦ x.

Recall that RB0 (A) denotes the kernel of the natural map RB(A) → B(A).

g 0 (A) denote the kernel of the map from RB(A)

g

e

g 0 (A) is the

We let RB

to B(A).

Equivalently, RB

g

image of RB0 (A) in RB(A).

Corollary 4.27. There is a natural exact sequence of RA -modules

g 0 (A) → RP

g 1 (A) → P(A).

e

0 → RB

Furthermore, the cokernel of the right-most map is annihilated by 2.

Proof. The exactness of the sequence follows from the commutative diagram with exact rows

0

0

/

g

RB(A)

/

e

B(A)

/

/

g 1 (A)

RP

/

e

P(A)

/

S̃2Z (U A )

=

S̃2Z (U A )

30

KEVIN HUTCHINSON

g

For the second statement, let x ∈ WA . Then p−1

+ [x] ∈ RP1 (A), since

−1

f

λ̃1 (p−1

+ [x]) = p+ (hh1 − xii hhxii) = 0 in RA

e

and p−1

+ [x] maps to 2 [x] in P(A).

We will also need the following corollary below.

Corollary 4.28. Let A be a field

h i or a local integral domain with infinite residue field. There are

natural isomorphisms of RA 12 -modules

h i

h i

h i

h i

g 1 (A) 1 .

g 0 (A) 1 RB0 (A) 1 IA RB(A) 1 IA RP

RB

2

2

2

2

g 0 (A) is annihilated by

Proof. By Corollary 4.8 the kernel of the surjective map RB0 (A) → RB

4, and the first equality follows.

The second equality is part of the statement of Lemma 2.4 when A is a field and is part of the

statement of Corollary 3.26 when A is a local integral domain.

e

For the third equality, we begin by observing that since GA acts trivially on P(A),

we have

h i

h i

1

1

g 1 (A)

g 0 (A)

IA RP

⊂ RB

2

2

by Corollary 4.27. On the other hand we have

h i

h i

h i

h i

1

g 0 (A) 1 = IA RB(A) 1 = IA RB(A)

g

g 1 (A) 1 .

RB

⊂ IA RP

2

2

2

2

5. Valuations

5.1. The specialization homomorphism revisited. Given a field F with a valuation v : F × →

Γ and corresponding residue field k, we let U = U F denote the corresponding group of units

and U1 = U1 (F) the units mapping to 1 in k× . The residue map U → k× will be denoted a 7→ ā.

Given any Rk -module M, we define the induced RF -module

MF := RF ⊗Z[U] M = RF ⊗Z[U/U 2 ] M.

Observe that when U1 = U12 then U/U 2 Gk so that MF = RF ⊗Rk M in this case, and there is

a natural (split) short exact sequence of groups

1 → Gk → GF → Γ/2 → 0

and Rk ⊂ RF naturally.

In [8] we proved the existence of a natural surjective specialization homomorphism

[F

S v : RP(F) → RP(k)

[ := RP(k)/(K (1) + Ik Dk ) = RP(k)/(K (1) + K (2) ).

where RP(k)

k

k

k

In this subsection, we revisit this specialization map and prove that it can be defined with

g F , rather than RP(k)

[ F . (It can be shown that there is no reasonable specialization

target RP(k)

homomorphism with target RP(k)F , however.)

Lemma 5.1. Let F be a field and let a ∈ F × .

g

(1) hai C F = C F + ψ2 (a) in RP(F).

g

(2) ψ2 (a) = ψ2 a−1 = ψ2 (−a) in RP(F).

Proof.

(1) This is an immediate consequence of the formula in Corollary 4.20 above.

H3 of SL2 of local rings

31

D E

(2) This follows immediately from (1) since hai = a−1 and h−1i C F = C F .

g

Note also, that in RP(F),

we have, by definition, that C F = [x] + h−1i [1 − x] for any x , 0, 1.

Theorem 5.2. There is a surjective RF -module homomorphism

g F

S v : RP(F) → RP(k)

1 ⊗ [ā] , v(a) = 0

1 ⊗ Ck , v(a) > 0

[a] 7→

−(1 ⊗ Ck ), v(a) < 0

Remark 5.3. The proof we give here follows closely the proof of Theorem 4.9 in [8]. Only the

following cases differ: Case (v) (a) and (b), Case (vii). These cases use Lemma 5.1, which in

turn relies on Theorem 4.19.

g F be

Proof. Let Z1 denote the set of symbols of the form [x] , x , 1 and let T : RF [Z1 ] → RP(k)

the unique RF -homomorphism given by

1 ⊗ [ā] , v(a) = 0

1 ⊗ Ck , v(a) > 0

[a] 7→

−(1 ⊗ Ck ), v(a) < 0

We must prove that T (S x,y ) = 0 for all x, y ∈ F × \ {1}.

Through the remainder of this proof we will adopt the following notation: Given x, y ∈ F × \{1},

we let

y

1−x

u = and w =

.

x

1−y

Note that

1 − x−1 y x − 1

= uw.

= ·

1 − y−1

x y−1

D

E

Thus, with this notation, S x,y becomes [x] − y + hxi [u] − x−1 − 1 [uw] + h1 − xi [w].

We divide the proof into several cases:

Case (i): v(x), v(y) , 0

Subcase (a): v(x) = v(y) > 0.

Then 1 − x, 1 − y ∈ U1 and hence w ∈ U1 , so that w̄ = 1 and uw = ū. Thus

D

E

T (S x,y ) = 1 ⊗ Ck − 1 ⊗ Ck + hxi ⊗ [ū] − x−1 − 1 ⊗ [ū] .

D

E

However, x−1 − 1 = x−1 (1 − x), so that x−1 − 1 ⊗ ū = hxi ⊗ h1 − x̄i [ū] = hxi ⊗ [ū],

and thus T (S x,y ) = 0 as required.

Subcase (b): v(x) = v(y) < 0.

Then u ∈ U and uw ∈ U1 so that w̄ = ū−1 . Thus

h i

T (S x,y ) = −1 ⊗ Ck + 1 ⊗ Ck + hxi ⊗ [ū] + h1 − xi ⊗ ū−1 .

h i

But 1 − x = −x(1 − x−1 ) and 1 − x−1 ∈ U1 , so that the last term is h−xi ⊗ ū−1 and

g F.

hence T (S x,y ) = hxi ⊗ ψ1 (ū) = 0 in RP(k)

Subcase (c): v(x) > v(y) > 0.

Then w ∈ U1 and v(u), v(uw) < 0. So

D

E

T (S x,y ) = 1 ⊗ Ck − 1 ⊗ Ck − hxi ⊗ Ck + x−1 − 1 ⊗ Ck .

32

KEVIN HUTCHINSON

D

E

But since x−1 −1 = x−1 (1− x) and 1− x ∈ U1 it follows that x−1 − 1 ⊗Ck = hxi⊗Ck

and hence T (S x,y ) = 0.