Residential Design Codes

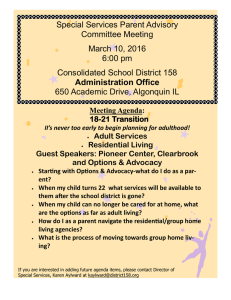

advertisement