Probate Law Resource Guide

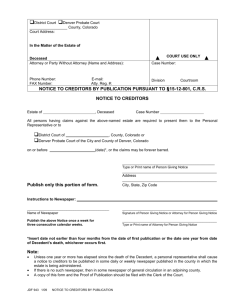

advertisement