A DRAMATICALLY DIFFERENT NSC?

advertisement

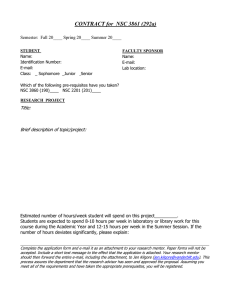

A DRAMATICALLY DIFFERENT NSC? PRESIDENT OBAMA’S USE OF THE NATIONAL SECURITY COUNCIL Michael Gordon Jackson Department of Political Science Regis College College Hall Weston, MA. 02493-1571 Michael.Jackson@regiscollege.edu Paper prepared for presentation at the Annual Meeting of the Western Political Science Association, Portland, Oregon, March 22-24, 2012 Abstract: There were expectations that President Obama’s National Security Council would be ‘dramatically different’ in tone and substance from previous administrations. With a presidential directive, the NSC was indeed structurally modified. However, Obama’s first NSC Adviser failed to satisfy the president’s expectations or vision about how the NSC would be used. With a new NSC adviser, the president would now manage the NSC in ways that would both reflect continuities with past NSC practices and his own priorities and personality. Obama’s management style of the NSC is orderly, calm, rational and pragmatic, with the president expecting focus, energy, and commitment from its staff members. The management model closely follows what is known as the ‘Scowcroft Model’ of NSC stewardship. 1 Introduction Promising change and new beginnings for America, Barack Obama’s administration took over the levers of power with great expectations in January 2009. How would the new president reform and streamline the organization and conduct of foreign policy? It was anticipated by many that Obama’s incoming foreign policy team would institute a sharp departure from the foreign policies of the Bush administration. There would be more changes than continuities associated with the administration’s global initiatives. One key issue was whether he would utilize the policy-making machinery of the National Security Council (NSC) in significant ways. In 1947, the NSC was first established by statute (The NSA 1947). It rapidly became clear that the president was prepared to authorize significant changes in relation to the NSC’s membership, structure, internal processes, and mission. Indeed, retired ex-Marine general, James Jones, Obama’s choice to be his first NSC Adviser, confidently asserted in the winter of 2009 that the NSC would be “dramatically different” from that of the Bush administration or any other administration’s NSC. In an interview, Jones stressed that the context for decision-making had changed. “The world that we live in has changed so dramatically in this decade that organizations that were created to meet a certain set of criteria no longer are terribly useful” (De Young 2009). As we near the end of Obama’s first term, there is enough evidence available to offer some preliminary analysis of whether Jones’ promise has been fulfilled. The purpose of this paper is to investigate the question by examining whether the president has truly changed the structure of the NSC, its staffing patterns, access channels and interagency processes. How does Obama use the NSC for decision-making? What is his “management style” in regards to the NSC? As will be demonstrated, the NSC has evolved in interesting ways, but not quite as “dramatically” as General Jones predicted. Let us first briefly review the broader question of the role of the NSC, the NSC Adviser, and how various presidents in the past chose to work with its policy-making and decision-making machinery. Background In the aftermath of World War II and the beginning of the Cold War, the Truman administration concluded that its national security policy institutions had to be updated to meet the new international challenges that the US was now facing. Indeed, there was an emerging consensus 2 that President Roosevelt had coordinated war efforts within the US by a leadership style characterized as “competitive chaos” between himself and players within the foreign policy bureaucracy (Inderfurth 2004: 2). With FDR, there was more ‘art’ than managerial science in his methods. There was recognition that more formal structures and processes for managing national security should be adopted and implemented. Truman in his memoirs observed, “I wanted one top level permanent setting in the government to concern itself with advising the president on high policy decisions concerning the security of the nation” (Truman 1956: 49). Instead of the ad hoc and at times inefficient tools used by President Roosevelt, a new agency infrastructure needed to be created that would fit the troubled and complicated Cold War era facing the Truman administration. As noted before; the National Security Act was passed in 1947. Along with other actions such as the establishment of the Department of Defense (DOD), the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) and a new US Air Force, the act also created the NSC. It was initially envisioned as becoming the focal point for senior policy coordination for foreign and defense policy making. But the NSC rapidly began to transform itself in keeping with the managerial preferences of subsequent presidents. Beyond being placed inside the Executive Office of the President (EOP), by National Security Act Amendments of 1949, its basic mission, structure, standard operating procedures, and staffing have evolved and been modified by presidents during the intervening 60 years. The NSC would be a dynamic institution that would change in line with the administrative styles of differing presidents. It certainly was not static in nature. There is also a modest, but important, body of scholarship which has described and analyzed the development, evolution, and history of the NSC. Though much of the record about the NSC remains generally classified beyond the Nixon administration, a substantial amount of analysis and discussion about the NSC has been generated by journalists and academics over the years. In one way or another, each president’s management style and use of the NSC has been covered in the literature since the Truman administration. A key generalization that has been advanced, not surprisingly, is that while the basic structure and mission of NSC has been a constant, how presidents actually choose to utilize it has varied over time. For example, Greenstein wrote extensively about Eisenhower’s style (Greenstein & Immerman 2000). Prados surveyed the institution of the NSC (Prados 1991). Burke has written a recent analysis of the role of NSC adviser and decision-making by presidents (Burke 2009). Two other influential works are by Inderfurth and Johnson (2004) and Rothkopf (2005). Daalder & Destler have also published an excellent investigation of the NSC adviser role (2009). Indeed, Daalder and Destler, have been coordinating the National Security Council Project associated with the Brookings Institution for an extended period of time, making available to scholars publications, facts, statistics, oral histories, and various media about the NSC. 3 It is a literature which is both critical and positive about how presidents have chosen to use the institution and potential of the NSC. A key point which unifies much of the scholarship is the fundamental issue of whether the relations between the NSC, the NSC advisers and their presidents are effective or dysfunctional. As Pfiffner notes, it usually boils down to three empirical and theoretical questions: “Political scientists who study presidential decision making have come to consider several factors as central to understanding White House organization and process: the level of centralization, the extent of multiple advocacy, and the use of honest brokers to manage advice to the president” (Phiffner 2011). The question of the extent to which a president chooses to centralize or decentralize the machinery of the NSC is a major one. In general, there is a trend for presidents, even when fully using the NSC, to ultimately concentrate final decision-making within small groups of advisers. Though Eisenhower once said to members of his cabinet, “You are my advisers. I want you to speak freely” and publicly talked about the importance of the NSC process for debate and creating policy options, the fact was that he preferred in the end to usually depend on small groups of advisers that he favored (2011). The second school of thought emphasizes the dynamics of “multiple advocacy” and presidential policy outcomes. According to Alexander George (1980/1972), the best decision-making flows from institutional structures and processes which strive to present the president with a full range of alternative options and contingencies for him to evaluate. “…the mere presence of differing views among White House staffers (does) not guarantee the effective presentation of alternatives to the president.” For a system of multiple advocacy to succeed, a structure had to be created for the purpose of facilitating the communication of differing points of view to the president. (2011). A third popular approach that has been used by scholars to analyze the NSC has been the “honest brokers” model. In following this style, the NSC advisers must not only ensure that the president receives multiple levels of advocacy from the foreign policy making bureaucracy, it must also be “balanced” when presented to the president. Presidents must have someone manage and filter information and differing options, in a thorough, fair, and effective way. As an “honest broker” the NSC adviser was not “just another policy advocate.” Rather, he must also be prepared and able to provide a “fair and balanced” presentation of information to the president and those other advisers serving him (Burke 2009) However, one approach since the Eisenhower administration that has often been cited as the template for how the NSC should be run effectively is the “Scowcroft” Model”. President George H. W. Bush appointed Lt. General Scowcroft as his NSC adviser. Scowcroft was greatly 4 respected for his bureaucratic prowess, collegiality, and ability to manage the NSC. Bush and Scowcroft in 1988 restructured the NSC. It would now have a Principals Committee, Deputies Committee and eight policy coordinating committees. Scowcroft’s goal was to create a system in which he would function as “honest broker” and coordinator of policy-making within the executive branch. His performance as NSC adviser has been praised. “The basic structural organization of interagency working groups, department deputies, and department principles organized in the George H.W. Bush administration has been retained for every succeeding presidential administration” up to and including, as will be shown, some key innovations introduced by the Obama administration in 2009 (Whittaker 2011). Another very important reason for the success of the “Scowcroft Model” of NSC advising, to be examined later, revolves around the question of how much the president trusts, and is willing to give access to, his NSC adviser. Here again, Bush and Scowcroft were extremely compatible with each other.1 At the start of the Obama administration, which approach (or approaches) about how to manage the institution of the NSC, did the new president prefer and adopt? Certainly the president had a wide range of recommendations to consider for how to use, if not reform, the NSC. There was no shortage of options that Obama could use to guide him in formulating his own views about how important the NSC was and how he should manage it. Reform of the NSC – Recommendations Ideas for reform of the NSC, before the Obama administration took office, were made available by journalists, business groups, academics, and “blue ribbon” commissions. One prominent defense policy analyst urged Obama to adopt the successful Eisenhower “model” for structuring and utilizing the NSC. “Under this structure, the president (Eisenhower) chaired the NSC meetings and, in leading the discussion, made a point of bringing out conflicts and differences by having everyone air their opinions.” Eisenhower demanded mandatory attendance at NSC meetings. During a four year period, President Eisenhower missed only six of 1 In an extensive interview with Brian Lamb of CSPAN in 1998, former president George H.W. Bush and his NSC adviser Gen. Brent Scowcroft, talked about how much respect and trust between them resulted in a strong bond between them. When asked by Lamb why he had co-authored his memoir A World Transformed with Scowcroft, Bush recalled: “Well, because Brent was such an integral part of the decision-making process as head of the National Security Council, the coordinator as well, bringing together very able but very different cabinet officers: Dick Cheney, Jimmy Baker, you name it. An NSC adviser has to coordinate and try to work out the differences between strong-willed cabinet people before the president has to decide everything. And so he is an integral part of everything I tried to do, and it just seemed like it would be a better, more thorough book if we collaborated. And so I asked him, and that was the genesis. That's how it happened.” Later in the interview, he was asked when he realized that the former general was someone he wanted to work with. Bush replied: “Well, ever since I can remember working with him--clearly, the time we started really working together was when he was running the NSC and I was at CIA. And I came in there from China with no professional intelligence experience. I'd been a consumer of intelligence. But Brent had lived through all the Church committee hearings and these turbulent times, and I just was dependent on him in order to have the confidence or the closeness to the White House that any director needs, and also to help me navigate through the mine fields. So it was there that I saw him working 1,000 hours a day, as he does, and that's where the respect started growing, right there” (Lamb 1998). 5 179 NSC meetings. The president created a Planning Board which issued policy papers to be weighed by the NSC. This Board’s mission was not “to reach solutions which represent merely a compromise of departmental positions.” In addition, Eisenhower organized “Study Groups” of senior officials to develop strategic insights. And, to assist those NSC decisions that advanced through the Planning Board, an Operations Coordinating Board (OCB) was established. Its task was to move and expedite decisions that seemed to be bogged down by bureaucratic inertia. In keeping with the form and spirit of Eisenhower’s NSC, Obama was urged to follow the precedent set by the former president, a model “characterized by the persistent involvement of the president and his senior decision makers, supported by a smart, tight knit group of strategists able to tap into a team of dedicated and informed subordinates and advisers.” Obama’s involvement had to be “direct” in formulating strategy within the institution of the NSC (Krepevich 2009). The incoming administration received advice from research centers such as the IBM Center for the Business of Government (Worley 2008). This report noted that in general, the NSC engages in three different functions: policy formation, oversight of policy implementation, and policy implementation itself. Without equivocation, their report advised the new president, “The National Security Council (NSC) is your principal mechanism for orchestrating the instruments of national power.” They recommended a series of steps: issue a presidential directive on Inauguration Day announcing what the structure of his NSC would consist of; avoid a “clean sweep” of Bush’s NSC organization by maintaining its staffing patterns until at least the second year of the administration; create a series of policy reviews to set the agenda and build interagency teams that Obama would use and support during periods of future crisis management; thoroughly use the NSC interagency process to take advantage of the “expertise resident in the executive branch”; “direct its energies”; be prepared to seek advice, when appropriate, beyond the confines of the NSC itself; and lead the NSC and other national security organs as directly as possible by himself. The report also urged President Obama to avoid “destructive competitions, between principals for who takes the lead role in foreign policy formulation and presentation. He should Issue clear assignments of roles and missions within the NSC system. During this same period, another commission – The Project on National Security Reform (PNSR), a group consisting of over three hundred national security officials, scholars, and professionals presented recommendations, in general, about how to reform the conduct, structures, and direction of US national security. The report was written by twenty principal contributors. Subsequently, a fair number of them would serve within the national security team of the new administration. The report bluntly concluded: 6 “…the basic deficiency of the current national system is that parochial departmental and agency interests, reinforced by Congress, paralyze interagency cooperation even as the variety, speed, and complexity of emerging security issues prevent the White House from effectively controlling the system. …the bottleneck….makes it all but impossible to bring human and material assets together into a coherent operational ensemble” The commission recommended that it would be a mistake for the “White House to centralize interagency missions. More than twenty-nine agencies or special groups report directly to the president.” With this situation, there might be the real possibility for “burn out” among the NSC staff. The commission then presents key recommendations; including establishing a Presidents Security Council (PSC) that would replace the NSC and Homeland Security Councils; establish by statute a new Director for National Security (DNS) within the EOP; mandate national security reviews; initiate effective interagency national security budget processes; and transform bad “knowledge-management systems” within the government (PNSR 2008). These recommendations/suggestions were a menu of choices that President Obama might choose to adopt and implement in his first term. As will be seen, though, the President, while influenced by some of these ideas, would rapidly restructure and use the NSC machinery in ways that fitted his own management style and his own expectations regarding interagency processes and who ultimately the right individual would be who could serve him as NSC adviser. Out of the Starting Gate – Obama’s NSC in the First Year As noted previously, General James Jones, Obama’s designated National Security adviser unequivocally declared that the NSC would be “dramatically different “from previous administrations. In an interview on Feb. 8, 2008, Jones outlined in some detail what the changes were that was being planned for the “new” NSC (De Young 2009). He stressed that he would run the NSC process and be the president’s primary conduit for information about national security. Communication by “back channels”, by other principals in government would be strictly controlled. He would give his advice to the president and make sure “minority opinion” would be represented to Obama, too. Most importantly, in keeping with the demands of the 21st century, the NSC would be elastic and cover more issue areas: “The whole concept of what of constitutes the membership of the national security community…which, historically has been, let’s face it, the Defense Department, the NSC itself and a little bit of the State Department, to the exclusion perhaps of the Energy Department, Commerce Department and Treasury, all the law enforcement agencies, the Drug Enforcement Administration, all of those things…especially in the moment we’re currently in, has got to embrace a broader membership.” To Jones, the NSC would deal with issues ranging from cyber security, global warming and energy sufficiency, to nation building. “We are going to reflect in the NSC all the regions of the world along some map line we can all agree on”. Powerful political players such as now Secretary of State Hillary Clinton or re-appointed Secretary of Defense, Robert Gates, would be 7 welcome in this new structure for national security policy making. Instead of a “team of rivals” Jones reportedly describes the new national security team as “colleagues” instead of competitors. Jones also noted that he intended to bring “military like discipline” to the NSC. He would chair meetings of the Principal’s group. In a meeting with Obama, Jones emphasized that the President fully agreed that he (Jones) would be in charge. “He (Obama) was clear about the role of the national security adviser.” Real innovation within the NSC was being promised by Jones. As will be seen, though for different reasons, the NSC would change in interesting ways, though not in the specific ways described by the first NSC adviser. On Feb. 13, 2009, President Obama issued Presidential Policy Directive 1 (PPD-1). In PPD-1, he described the structure and mission of the NSC as it would exist in his administration. The NSC would be the “principal forum for consideration of national security policy issues requiring Presidential determination”. So far, this represented little change from precedents established by past administrations, especially Brent Scowcroft’s term as NSC adviser in the first Bush administration. The PDD stated there would be a Principals Committee “the senior interagency forum for consideration of policy issues affecting national security” chaired by the NSC adviser, a Deputies Committee that “will review and monitor the work of the NSC interagency process” and “shall be responsible for day-to-day crisis management”, chaired by the Deputy NSC adviser. There also would be new Interagency Policy Committees (IPCs) that would be given the major mission for inter-agency coordination of national security issues. The NSC/IPCs would replace the existing system of Policy Coordination Committees. (PDD-1 2009) In addition, the NSC would expand statutory limitations on membership, increasing the number to eleven Obama principals, including the Secretary of Treasury, Attorney General and Secretary of Homeland Security. Furthermore, when either economic issues, domestic security, counterterrorism, science and technology problems and others, were being considered, key officials from relevant and affected departments could be asked to participate. How different was President Obama’s NSC structure in contrast to previous administrations? NSC scholar John P. Burke, in an analysis of the first six months of the Obama NSC, was correct to note at the time - not very much. Similar to other administrations, formal meetings of the NSC would be superseded by having the president also meeting with small groups of principals in important meetings. In the opinion of Burke, “Adoption of this meeting structure (in PDD1) plus the rest of the Scowcroft model was the centerpiece of the February 13 directive. Organizational continuity rather change was the more important order of the day” (Burke 2009). This is not to say that structural changes within the NSC were not adopted and implemented. In keeping with the Obama administration’s broader interpretation of the scope of national security, in May 2009 the White House Office of Homeland Security was subsumed within the 8 NSC. The Homeland Security Council (HSC) would now report to the NSC adviser. The staffs of the HSC and NSC would be combined and merged. What was the purpose of this restructuring? To end, “The artificial divide between White House staff who have been dealing with national security and homeland security issues”. Obama also not reluctant to establish new national security groups, such as the White House “cybersecurity” office. Members of the NSC would, when required, work closely with staff of office such as the National Economic Council (NEC). The new NSC could now deal more effectively with issues such as terrorism, cross border crime, pandemics, disasters, and other “non-traditional” threats to national security. Moreover, the assistant to the President for Homeland Security would have direct access to the President but would also report to the NSC adviser. These organizational changes demonstrated the president’s desire to include key domestic issues within the purview of the NSC and national security in general. “The integration of NSC and Homeland Security Council staffs may work to overcome the intelligence and law enforcement divide that many observers believe existed prior to 9/11. It may also facilitate closer cooperation of federal agencies and state, local, and tribal entities in dealing with homeland security issues” (Best, 2012, p. 23-24). Right from the start of the Obama administration, a new NSC team, with a broader mandate, had been established by the President, headed by General Jones as NSC adviser. The president had created NSC machinery very much respectful of past precedents but with some new structural adaptations created to avoid backchannel tensions and to more effectively respond to the new dimensions of 21st century national security. Obama would be fully engaged with the NSC. And it would reflect his world view regarding the challenges facing the US. However, some analysts and observers, even at the beginning of the administration, were skeptical about whether Obama’s NSC would be effective. Their doubts did not center on questions about the new structure or mission of the NSC. Rather, right from the beginning there were doubts about the leadership of the NSC. In short, was General Jones the right man to be Obama’s NSC adviser? One top NSC scholar, wondered whether Jones would be able to develop a management style “that is consistent with President Obama’s informal, substantively intense, and rapid decision making” style. Looking at the past record of those NSC advisers who were judged to be the best, he noted that the most successful NSC advisers “were effective thanks to strong personal and policy relationships with their presidents”. Was it a good match between the ex-marine general and the change agent personified by Barack Obama? It was known that Jones was not 9 personally close to Obama and had met with him before his appointment only a few times before (Destler 2009). Burke was also uneasy about Jones’ appointment. Though he was fair in outlining some of Jones’ strengths, he was quite prescient in anticipating some of the problems that characterized future relations between the president and his NSC adviser. He speculated about whether Jones was trying to be an “honest broker” in respect to powerful cabinet chiefs such as Clinton or Gates. Would he be too weak “more a passive coordinator” than a true honest broker? Burke describes troubling charges in the press, for example, such as the assertion that Jones seemed to “attend meetings” rather than “lead them”. One reporter described how during a meeting about Afghanistan policy, “officials in the room” noted that the general “seldom voiced his own opinions…Instead he preferred to go around the table collecting the views of others” (Burke 2009). Was Jones’ reported reticence simply an example of how he viewed his role as NSC adviser? Or, was there a deeper issue? Naturally, much of this could have been typical Washington “beltway” gossip or a manifestation of interdepartmental jealousies. As will be seen, though, the problem appeared not to be the new structure of the NSC, but the issue of whether the managerial skills and personality of the NSC adviser matched and complemented those of the president. This “human factor” would prove to be decisive in this case. The Resignation of General Jones – NSC Reshuffling Within a year, the importance of the “human factor” was front and center. Articles in the press and other forums about the Obama administration began to paint a negative picture in which more and more, Jones was described as exerting too little authority as NSC adviser. Nor was he up to the fast pace and give and take associated with the post. Most damaging, it was perceived that Jones in reality did not have a direct line to President Obama; other advisers did. As a result, not having a direct line to President seemed to encourage other advisers to bypass him. In Bob Woodward’s depiction of the decision-making process about waging war in the Obama White House, he noted how Jones resented being ignored by other advisers, calling them “waterbugs”. In one incident, when the Chief of Staff walked pass his office and entered the Oval House first, Jones said, “I’m the national security adviser…When you come down here, come see me” (Lee 2010). In a fast paced White House environment, it was observed that the NSC adviser lacked energy and passion for the job. Unlike others, he did not put in regular 18 hour work days, seven days a week. Indeed, Jones often left his office around 7:00PM and finished work for the day; or, he would bicycle home for lunch. In addition, key players felt that too often he was simply absent, engaging in ceremonial duties having little to do with NSC management. I.M. Destler was quite 10 critical about Jones work habits and performance. “He’s not very visible. I’m a skeptic on whether Jones has the sort of flexibility and ability” to keep up. Throwing fuel upon the fire, Jones himself noted “I’m only an outsider…but I’m a 20 years-older-than-anybody-around outsider (Lee 2010). More seriously, some in the press made the charge that Jones had little interest in managing the “inter-agency” process, a key task for any NSC adviser. He would travel frequently, be absent from Principals meetings with the president himself having to chair the meeting, not the NSC adviser. Jones would later state he did not have a taste for bureaucratic maneuvering. Indeed, in a speech to the Atlantic Council, Jones perhaps ruefully recalled, “I fondly remember the (Atlantic Council) as a place where people actually did what you asked them to do. In my new role (NSC adviser) I’m finding out that an order is a basis for negotiation” (Luce and Dombey 2010). The president shared these widening concerns about his NSC adviser. And, Obama was willing to cut his loses sooner rather than later. For different reasons, Obama earlier had sacked Admiral Dennis Blair, Director of National Intelligence. And in the case of the general, the president would not hesitate to act and make changes in this case, either. In October 2010, General Jones announced his resignation as NSC adviser. Because of differences in work ethic, conceptions about the role of NSC adviser, and increasing lack of confidence and access to the president, President Obama’s first choice of NSC adviser was a failure. But immediately, his replacement, Deputy NSC adviser Thomas Donilon, was named to replace General Jones. Soon after this, the outline and content of how the president really intended to use and manage his NSC became apparent. Donilon would turn out to be the perfect choice. President Obama and His New NSC Adviser Thomas Donilon – A Meeting of Minds and Philosophy Who was this new NSC adviser? The announcement was not made without some controversy. Secretary of Defense Gates reportedly said at one time that if Donilon became NSC adviser it would be “disastrous” (Luce 2010). Nevertheless, Gates would come to express his support for the new NSC Adviser. And Donilon’s management style, background, political savvy, bureaucratic expertise, tone, and energy levels, would match those of the president and other members of his NSC team. And, he would be perceived and admired for his effectiveness and compatibility with the expectations of President Obama. With the initial exception of Gates, Donilon’s appointment was praised. He was described by one administration official as having a “lawyer-like, aggressive style” (Lee 2010). Strobe Talbott, a prominent foreign policy analyst, declared that he was an “excellent choice” for the 11 role of NSC adviser “He (Donilon) has an acutely attuned ear for how things work, knows all the players and, crucially, understands the need for domestic political support to move foreign policy goals forward” (Luce 2010). From the beginning, there was a general consensus that Donilon’s bureaucratic skills, hyperenergy, management style, focus, and access to the president, would be a plus. And, most importantly, he was, according to President Obama “one of my closest advisers” (Destler 2010). Furthermore, in keeping with the Scowcroft model for optimal presidential-NSC adviser relations, both Obama and Donilon strongly respected and trusted one another.2 The Donilon NSC became a changed institution with the departure of Jones. Donilon would get things done in the manner the president wanted. Indeed, Donilon was described by one insider as “the most powerful man in the White House whose name isn’t widely known.” The new NSC adviser made the institution and processes work. His workload was described as “clinically insane”. 270 Deputies meetings were chaired by Donilon. Four to six hours a day would be spent within Deputies and Principles meetings. (Luce and Demby 2010). The NSC became more organized and disciplined, with effective paper trails being created, and a network of effective oral communications between members being instituted. It was noted during the Libyan crisis of 2011 that Donilon did what he was expected to do by Obama. He set up decision-making and policy-making processes for the president to make his choices and in ways that would allow his orders to be properly implemented. Donilon was described as not being a “strategic thinker” about national security. He left that to the president and other principals. Instead the NSC adviser provided “process, enforcing order and structure for a president who deeply values both”. Donilon would manage a systematic process for the president to separate chaos from impeding his decision-making (Nicholas and Parsons 2011). Both Donilon and Obama had been trained as lawyers. Both of them valued the application of logic and order in making decisions. 2 In 1999, as part of Brookings Institution ongoing series of oral history roundtables about the NSC, Scowcroft talked about the importance of any NSC adviser having to gain the trust and confidence of those working with him. “SCOWCROFT: I’ll start. First, some general remarks. Mine would be that it’s always more exciting to be the adviser, but if you are not the honest broker, you don’t have the confidence of the other members of the NSC. If you don’t have their confidence, then the system doesn’t work, because they will go around you to get to the president and then you fracture the system. My sense is that in order for the system to work, you first have to establish yourself in the confidence of your colleagues to convince them you are not going to pull fast ones on them. That means when you are in there with the president alone, which you are more than anybody else, that you will represent them fairly. And if you begin with that, I don’t know that there is much conflict. It seems to me that the first responsibility is to present what you know of the community views. And after you have done that, then you are free to be an adviser.” Scowcroft also described the incredible amount of work that has to be done in the NSC. “Scowcroft: No. The work is terrible. I told everybody I hired that I would be amazed if they could stay longer than two years, because I was going to work them seven days a week, sixteen hours a day.” (Daalder and Destler 1999: 2,27). 12 Donilon’s privilege of access to Obama was assured. Every morning at 9:30AM, the NSC adviser would brief the president about national security. In September 2011, speaking before the Economic Club of Washington DC, Donilon described in some detail how the NSC worked and what his role was. After observing that many people around the president were not shy about expressing themselves, he recalled how the NSC machinery and routine functioned in the weeks leading up to the Bin Laden raid. He told the audience that twenty-four interagency meetings were held before the final raid in May of 2011. In addition, another six meetings between the Principals Group took place in the month before the raid into Pakistan. There was “robust debate”. Ultimately, at the end of discussions, “The President makes the decisions”. And, Donilon noted, there were no leaks! To Donilon, this demonstrated the commitment and seriousness of the NSC groups. “We put in place a system and a process which I think has been really essential to our success in the foreign policy, national security side. And, it has these elements to it”: “One process, the National Security Council process…not competing processes. There were not back doors to the President. There were no other national security processes over here that compete. One process. And everybody signed up at the beginning to that being the exclusive process by which national security decisions will be made, number one. Number two, that the decisions made would be executed by this group faithfully. Number three, that when you came to the table, you came to the table with a view and the view of your building [Cabinet department]. Number four, that I would commit on our side that decisions of each meeting would be published in writing in 24 hours so that people could see what their assignments were and they could object if they disagreed with it so there’s absolute clarity at the end of the day. “ Later during his talk, Donilon was asked whether he followed any particular management model for the NSC. He replied: “Now, you ask about models. There are different models. I think in terms of process management (emphasis mine), I do think that there’s one person who’s had the job twice and did put in place kind of this committee system…this decision-making system..in the late ‘80s that we follow today. That’s Brent Scowcroft, who I think did a tremendous job.” Asked about he conducted his daily morning NSC briefing of the president, Donilon characterized it as a combination of intelligence and a policy briefing. The President and Vice President are the two principal people he addresses. First, either the Director of National Intelligence or head of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) present a briefing about the latest intelligence about national security. Donilon then noted: 13 “And then we will have kind a policy briefing that I lead, with an analysis of the intelligence and its implications, and then the three or four or five or six most important things going on in the world that day. There may be three of four decisions that we want to reach during the course of the briefing about issues that have come up during the course of the 24 hours since the last briefing”. And, Donilon also made it clear how much the principle player in the NSC process was the president himself. Asked if the president prefers to read things or just be only briefed like some past presidents “We respect to that, the President has read all the materials before we meet with him…If you start briefing on things that are in the newspaper, it’s not going to be a long career as briefer to President Obama “ (Economic Club 2011) Because his president is prepared, Donilon established procedures that in turn demand preparation from all other participants during NSC meetings. Other players in the federal bureaucracy are aware that decisions are made efficiently and as promptly as possible by the NSC, that Donilon has the ear of the president and can get the president to respond to requests in real time. Even with the usual issues of competing and bruised egos associated with every NSC, the Obama team had developed a comparatively high functioning relationship with one another. In the opinion of David Rothkopf, author of a recent book about the NSC, Obama’s NSC ranks “…among the best since the Scowcroft era.” (Rothkopf 2011). It is clear that President Obama views the NSC machinery and right personal chemistry and trust with the NSC adviser as a very important component for his own decision-making about national security options and issues. The question to be addressed now is what the president’s own management skills are in relation to the NSC. President Obama’s Management Style & the NSC By the end of President Obama’s first term, it is now possible to offer some generalizations about his use of NSC and management style. As noted earlier, primary sources are hard to come by and no memoirs by key actors have been published. But, the following points can reasonably be made. The NSC Machinery is Heavily Used and Valued by the President It is apparent that the president uses the NSC machinery frequently for his foreign policy and national security decision-making. With hundreds of meetings taking place within the NSC system, with meetings of the Principals and Deputies groups, in which, at times, even he will chair, the President appears to value the information, options offered, and forum, provided by his NSC. The NSC is not a marginal player in the Obama administration. 14 Indeed, looking at a chronology of the decision-making that led up to the Bin Laden raid, it is quite evident how important the NSC and process is to President Obama. Centralized and Multiple Advocacies Foreign policy and national security issues are weighed within a centralized structure in the Obama White House. All of the players, whether authorized by statute or involved because of issue areas they are associated with, are expected to participate in the key forums of the NSC. “Back channel” communications and bureaucratic end runs around the NSC process are frowned upon by the president. To assist him in his decision-making, participants are expected to fully present both their own opinions and those of their department or agencies. Vigorous, but orderly, debate among the advocates would be standard operating procedure. But, it would not necessarily be a “team of rivals”. Instead, a team of advocates would also be committed to abide by the NSC process, and goals of the administration or, as General Jones earlier put it, a “team of colleagues”. And, once the president makes the decision, all are expected to fully implement the action points set forth by Obama. Lawrence Summers, former head of the National Economic Council (NEC) during the first years of the Obama administration, was once asked about comparing Obama’s and Bill Clinton’s management styles (Isaacson 2011). Perhaps with a bit tongue in cheek, he reflects: “Let's do it the other way. You're working for Barack Obama. If you have a meeting scheduled at ten o'clock, there's a 25% chance that the meeting will begin before ten o'clock, and there's a -- you know what's coming, and there's a 70% chance that the meeting will have begun by 10:15. If you wrote Barack Obama a memo before the meeting, it is a virtual certainty that he will have read it. If you seek to explain the memo you wrote to him during the meeting, he will cut you off, and he will be irritated. He, as the leader of the meeting, will ask one or two questions to kick the tires, but will basically focus on how whatever subject you're talking about fits with the broad vision and approaches of his presidency. He will basically take the attitude if you're his financial adviser, that if you can't -- it's up to you to figure out whether preferred stock or subordinated debt is the appropriate financial instrument for your bailout, and that if he doesn't trust you to figure it out, he'll get a new financial adviser, but that is not the question on which he is going to spend time. So it's a very focused executive, big picture guidance, disciplined approach. At the appointed time, his secretary will come in and will bring a card that says it's time for his next meeting, and you will be out of that office within five minutes. It is a certainty. That's working for Barack Obama, and it is a wonderful experience.” 15 Summers added that Clinton’s management style was wonderful too, but quite different in how it operated.3 Regular Order & Proper Procedures Orderly process and routines are very much valued by President Obama. Time management is important. With the exception of a few close aides and a small circle of principals who have call up or walk in privileges to the Oval Office, the president expects the NSC adviser to manage the machinery of national security decision-making, help prepare and formulate a range of options for the president to consider, and in general manage the flow of access to him. Donilon knows what his president wants and expects from the NSC system. Obama did not want an NSC adviser who is a “show boater” or superstar, such as a Henry Kissinger or Zbigniew Brzezinski. The president works best with a variant of the Scowcroft model, in which the adviser is low profile, committed to the president, has earned his trust, and manages the NSC effectively and orderly. You have not seen too many appearances by Donilon on political shows such as “Hardball” or “Meet the Press”. Proper order would be expected for working groups, Deputies and Principals meetings. Like the Scowcroft team, it was anticipated that the NSC would work “as an effective policy-options producer, interagency-coordination process, and final decision mechanism for the principals and the president’. According to Michael Crowley “process is not simply the poor cousin of strategy”. Regular order within the NSC was essential to please the president. “...a system that gives the president a diversity of views with minimal infighting and back-channel maneuvering, little leaking to the press, and public airing of dirty laundry” (Burke 2009). President Obama is Not Reluctant to Make Personnel Changes Some presidents try to avoid unpleasant actions like changing personnel that do not work out or disappoint them. One thinks of the famous incident in which President Reagan 3 On the other hand, according to Summers, it was a different experience working for Bill Clinton. “Working for Bill Clinton is also a wonderful experience. It is a different experience.The probability that your meeting will begin before ten o'clock is zero.The probability that there is compensation for the fact that your meeting will begin late, it is virtually certain to end late. Bill Clinton has a 30% chance of having read your memo before the meeting. Bill Clinton will, however, with near certainty, have some set of quite detailed and thoughtful perspectives to offer on your topic. He will say things like "I was in the White House library reading the Journal of Finance, and there's some really interesting thinking about the role of dividends in the system." "I went to a conference at the Brookings Institution 11 years ago, and do you know that there's a really interesting experiment with providing credit access in Tennessee?" "Did you read the latest issue of -- the Asian edition of The Economist? It had a perspective on Thailand that you might want to think about." There was a stunning, I mean you know, while he wasn't reading your memo, it wasn't that he wasn't doing anything about it. So it was a very different kind of experience that was also extraordinary in its way. I think the nation has been fortunate to have two such thoughtful, purposeful, highly intelligent and focused people, who have served as President, and it’s certainly been my good fortune to work for both of them, with their rather different styles” (Isaacscon 2011). 16 supposedly took one of his staff to the “wood shed” to express his displeasure. In contrast, Obama has demonstrated with his firings of his first NSC adviser General Jones and other officials, that if he is not satisfied with their performance, he will change staff in order to provide the process, energy, and commitment he seeks. He will insist on structuring a team that suits him and his goals. And, he demands results. The President is His Own ‘Honest Broker” He is in Charge The NSC is the president’s machine to use. It doesn’t control him; it serves him. For example, during the debate about whether to approve a “surge” of American forces into Afghanistan, President Obama was not satisfied with the options being given to him. In turn, he wrote a memo that outlined his thinking in precise detail. Cerebral and calm, the president has a management style in which he seeks out advice, weighs differing opinions, but let’s all know that the buck stops with him. There is a story that the president, frustrated with his then Chief of Staff, told him to push for more options”. “Get me some other people’s opinions on this…I want more than what’s in this room” (Rudalevige 2009, p. 19). Furthermore, Obama strives for consensus among those who participate in the NSC process. His style of decision-making is not from the “gut”; the constitutional lawyer in him wants options that are logical and rational, not driven by emotions of the moment. His hair will not be “on fire” nor does he want anyone else in his administration running around with their hair on fire. In his search for options to consider, he is calmly assertive – cautious, pragmatic, not ideological. In different forums, he president himself confirms this portrait of his decision-making and managerial style. According to Obama, a priority was putting “together the best people and have them work as a team; insisting on analytical rigor in evaluating the nature of the problem; making sure that dissenting voices are heard and that a range of options are (sic) explored”. To Obama, he has to make decisions based on “information and not emotions”. Bob Woodward describes Obama’s style during the deliberations about the war in Afghanistan (Woodward 2010). Should the mission be to defeat or degrade the Taliban? Should there be a “surge” of 30,000 or 40,000 US combat troops into Afghanistan Obama took his time making up his mind over several months. Former Vice-President Cheney accused the president of “dithering” and not being able to act decisively. Obama stated “I welcome debate among my team, but I won’t tolerate division”. At one point, Obama chastised the military for giving him four options, but only one that was realistic. The president wanted more. To make it clear, Obama himself specified in writing what he wanted, i.e., initiate a surge of only 30,000 personnel, not 40,000 as some in the Pentagon 17 pushed for. As one general described, in admiring terms, the President’s style for making hard decisions and his willingness to outline options himself was impressive, “There’s not a president in history that’s dictated five single-spaced pages in his life. That’s what the staff gets paid to do” (Pfiffner 2011) Is this micromanaging in action? This not a persuasive criticism. As Phfiffer put it, not wanting an honest broker per se, “Obama himself delved deeply into the major policies of his administration”. When not satisfied with the options being presented to him, as with the debate about the surge in Afghanistan, he produced a memo that specified exactly what he wanted. In essence, Obama is a president who can separate the analytical policy wheat from the chaff. Nor does he tolerate fools and those who do not meet his high expectations regarding performance and output. Final thoughts The first term of the Obama administration has grappled with a wide range of foreign policy and national security issues. He approved of “resets” regarding US-Russian relations. He has skillfully managed ties with China while beginning the process of shifting US assets back to the Pacific region. Obama has been in the midst of creating a sanctions regime against Iran, working with the NATO intervention into Libya, formally ending US combat in Iraq, attempting to balance US national interests with the upheavals associated with the Arab Spring, forming a coalition to defeat Bin Laden’s Al Queda and its international franchises. He has had his hands full trying to help manage the turbulence within global financial, monetary, and trading relations. Indeed, he has been an engaged and assertive president in regards to global policy issues. The appraisal of how successful Obama foreign policy is continuing. Brent Scowcroft, participating in a series of oral history roundtables about the NSC, put it best when he commented about how the NSC can be successful. “The NSC system was really developed to serve an activist president in foreign policy…I don’t know that the system works all that well when you don’t have the president there all the time, because by himself the national security adviser can’t really do it. He’s junior to all the other people. He needs that moral authority (Daalder and Destler 1999: 35). It can be asserted, then, that President Obama has created a NSC system, with the right mix of personnel, that works well with his management style. Whether he is reelected in 2012, it is a safe assumption that the president will continue to preside, and manage, his NSC team with the same calm and logic that he has exhibited during his first team. But, especially if he is a one-term president, more memoirs, analysis, and opportunities for interviews with ex-NSC staff, will become available for scholars to either validate the 18 argument that his management of the NSC has been effective, or challenge and refute the case with a negative assessment based on new evidence. REFERENCES Best, Richard A. Jr. 2011. The National Security Council: An Organizational Assessment. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. Burke, John P. 2009. “The Obama National Security System and Process: At the Six Month Mark,” White House Transition Project Report. Online Edition. -------. 2009. Honest Broker?: The National Security Advisor and Presidential Decision Making. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. Brown, Cody M. 2008. The National Security Council: A Legal History of the President’s Most Powerful Advisers. Washington, D.C.: Center for the Study of the Presidency, Project on National Security Reform. Clemons, Steve. 2011. “Obama’s Donilon Machine,” The Washington Note (October 27, 2011): Online Edition. Cooper, Helene. 2010. “The Adviser at the Heart of National Security,” The New York Times (July 10, 2010): A6. Retrieved from Lexis-Nexis Database. Daalder, Ivo H. and I. M. Destler. 2009. In the Shadow of the White House: Profiles of the National Security Advisers and the Presidents They Served: From JFK to George W. Bush. New York: Simon & Schuster. -------. October 1999. The National Security Council Project: Oral History Roundtables - The Role of the National Security Adviser. College Park, MD : Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland, School of Public Affairs, University of Maryland ; Washington, DC : Brookings Institution. Destler, I. M. 2010. “Donilon to the Rescue?” Foreign Affairs Magazine (October 13, 2010): Online Edition. -------. 2009. “Jonestown: Will Obama’s National Security Council Be Dramatically Different?” Foreign Affairs Magazine (April 30, 2009): Online Edition. DeYoung, Karen. 2009. “Obama’s NSC Will Get New Power,” The Washington Post (February 8, 2009): A01. Retrieved from Lexis-Nexis Database. 19 Economic Club of Washington, D.C. 2011. Speech & Interview with Thomas Donilon, National Security Adviser (September 16, 2011) Washington, D.C.: Federal News Service. Greenstein, Fred I. and Richard H. Immerman. 2000. “Effective National Security Advising: Recovering the Eisenhower Legacy,” Political Science Quarterly 115(3): Online Edition. Horowitz, Jason. 2010. “Is the Donilon Doctrine the New New World Order?” The Washington Post (December 21, 2010): C01. Retrieved from Lexis-Nexis Database. Ignatius, David. 2010. “Foreign Policy at Cruising Speed,” The Washington Post (April 15, 2010): A21. Retrieved from Lexis-Nexis Database. -------. 2010. “Some Foreign Policy Spine,” The Washington Post (December 26, 2010): A27. Retrieved from Lexis-Nexis Database. Inderfurth, Karl and Loch K. Johnson. 2004. Fateful Decisions: Inside the National Security Council. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Isaacson, Walter. 2011. “Inside the Oval Office: The Management Styles of Clinton and Obama,” CNNMoney (July 25, 2011). Online Edition. Kornblut, Anne E. and Scott Wilson. 2010. “White House Hard Fit for Ex-Military Officers; Transitions to Obama Administration Have Been Turbulent,” The Washington Post (May 25, 2010): A02. Retrieved from Lexis-Nexis Database. Krepinevich, Andrew F. and Barry D. Watts. 2009. “Lost at the NSC,” The National Interest 99(January-February 2009: 63. Retrieved from Online Database. Lamb, Brian. 1998. “Interview with President George H. W. Bush and General Brent Scowcroft – A World Transformed,” CSPAN Booknotes (October 4, 1998). Online edition. Lee, Carol E. and Gordon Lubold. 2010. “Donilon to Replace Jones,” Politico (October 8, 2010): Online Edition. Luce, Edward. 2010. “Obama’s Security Adviser Quits,” Financial Times (London, England) (October 9, 2010): pg. 3. Retrieved from Lexis-Nexis Database. ------- and Daniel Dombey. 2010. “Waiting on a Sun King,” Financial Times (London, England) (March 31, 2010): pg. 11. Retrieved from Lexis-Nexis Database. Nicholas, Peter and Christi Parsons. 2011. “National Security Chief Keeps a Low Profile” Los Angeles Times (April 29, 2011): Online Edition. 20 Obama, Barack. 2009). “Presidential Policy Directive – 1 – Organization of the National Security System,” White House Memorandum & PPD (February 13, 2009): Retrieved from Online. Pfiffner, James P. 2011. “Decision-making in the Obama White House,” Presidential Studies Quarterly 41(2): (June 2011): p. 344. Retrieved from Online Database. Prados, John. 1991. Keepers of the Keys: A History of the National Security Council from Truman to Bush. New York: Morrow. Project on National Security Reform – PNSR. 2008. Forging a New Shield: Executive Summary. Project on National Security Reform & Center for the Study of the Presidency. Retrieved Online. Rothkopf, David. 2011. “The President and the Donilon NSC After a Year and the Challenges Ahead,” Foreign Policy (October 25, 2011). Online Edition. Rudalevige, Andrew. 2009. “Rivals or a Team? Competitive Advisory Institutions and the Obama Administration,” Paper. American Political Science Association Annual Meeting, Toronto, Ontario, September 3-6, 2009. Online Edition. -------. 2009. “A Thousand Envoys Bloom,” The National Interest (May/June 2009): pg. 15. Online Edition. -------. 2005. Running the World: The Inside Story of the National Security Council and the Architects of American Power. New York, NY: Public Affairs. United States. Department of State. Office of the Historian. 1999. History of the National Security Council, 1947-1997. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Public Affairs, U.S. Department of State. Whittaker, Alan G., Brown, Shannon A., Smith, Frederick C., & McKune, Elizabeth (2011). The National Security Policy Process: The National Security Council and Interagency System. (Research Report, August 15, 2011, Annual Update). Washington, D.C.: Industrial College of the Armed Forces, National Defense University, U.S. Department of Defense. Woodward, Bob. 2010. Obama’s Wars. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. Worley, Robert D. 2008. The National Security Council: Recommendations for the New President. Washington, D.C.: IBM Center for the Business of Government. 21