Document/Base paper - PG Embedded systems

advertisement

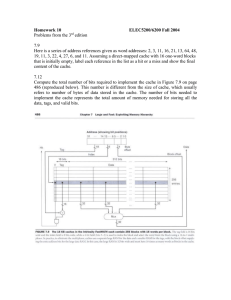

102 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON VERY LARGE SCALE INTEGRATION (VLSI) SYSTEMS, VOL. 21, NO. 1, JANUARY 2013 An Energy-Efficient L2 Cache Architecture Using Way Tag Information Under Write-Through Policy Jianwei Dai and Lei Wang, Senior Member, IEEE Abstract—Many high-performance microprocessors employ cache write-through policy for performance improvement and at the same time achieving good tolerance to soft errors in on-chip caches. However, write-through policy also incurs large energy overhead due to the increased accesses to caches at the lower level (e.g., L2 caches) during write operations. In this paper, we propose a new cache architecture referred to as way-tagged cache to improve the energy efficiency of write-through caches. By maintaining the way tags of L2 cache in the L1 cache during read operations, the proposed technique enables L2 cache to work in an equivalent direct-mapping manner during write hits, which account for the majority of L2 cache accesses. This leads to significant energy reduction without performance degradation. Simulation results on the SPEC CPU2000 benchmarks demonstrate that the proposed technique achieves 65.4% energy savings in L2 caches on average with only 0.02% area overhead and no performance degradation. Similar results are also obtained under different L1 and L2 cache configurations. Furthermore, the idea of way tagging can be applied to existing low-power cache design techniques to further improve energy efficiency. Index Terms—Cache, low power, write-through policy. I. INTRODUCTION M ULTI-LEVEL on-chip cache systems have been widely adopted in high-performance microprocessors [1]–[3]. To keep data consistence throughout the memory hierarchy, write-through and write-back policies are commonly employed. Under the write-back policy, a modified cache block is copied back to its corresponding lower level cache only when the block is about to be replaced. While under the write-through policy, all copies of a cache block are updated immediately after the cache block is modified at the current cache, even though the block might not be evicted. As a result, the write-through policy maintains identical data copies at all levels of the cache hierarchy throughout most of their life time of execution. This feature is important as CMOS technology is scaled into the nanometer range, where soft errors have emerged as a major reliability issue in on-chip cache systems. It has been reported Manuscript received March 28, 2011; revised July 15, 2011 and October 08, 2011; accepted December 07, 2011. Date of publication January 26, 2012; date of current version December 19, 2012. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant CNS-0954037, Grant CNS-1127084, and in part by the University of Connecticut Faculty Research Grant 443874. J. Dai is with Intel Corporation, Hillsboro, OH 97124 USA (e-mail: jianwei. dai@engr.uconn.edu). L. Wang is with the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269 USA (e-mail: leiwang@engr.uconn. edu). Digital Object Identifier 10.1109/TVLSI.2011.2181879 that single-event multi-bit upsets are getting worse in on-chip memories [7]–[9]. Currently, this problem has been addressed at different levels of the design abstraction. At the architecture level, an effective solution is to keep data consistent among different levels of the memory hierarchy to prevent the system from collapse due to soft errors [10]–[12]. Benefited from immediate update, cache write-through policy is inherently tolerant to soft errors because the data at all related levels of the cache hierarchy are always kept consistent. Due to this feature, many high-performance microprocessor designs have adopted the write-through policy [13]–[15]. While enabling better tolerance to soft errors, the write-through policy also incurs large energy overhead. This is because under the write-through policy, caches at the lower level experience more accesses during write operations. Consider a two-level (i.e., Level-1 and Level-2) cache system for example. If the L1 data cache implements the write-back policy, a write hit in the L1 cache does not need to access the L2 cache. In contrast, if the L1 cache is write-through, then both L1 and L2 caches need to be accessed for every write operation. Obviously, the write-through policy incurs more write accesses in the L2 cache, which in turn increases the energy consumption of the cache system. Power dissipation is now considered as one of the critical issues in cache design. Studies have shown that on-chip caches can consume about 50% of the total power in high-performance microprocessors [4]–[6]. In this paper, we propose a new cache architecture, referred to as way-tagged cache, to improve the energy efficiency of write-through cache systems with minimal area overhead and no performance degradation. Consider a two-level cache hierarchy, where the L1 data cache is write-through and the L2 cache is inclusive for high performance. It is observed that all the data residing in the L1 cache will have copies in the L2 cache. In addition, the locations of these copies in the L2 cache will not change until they are evicted from the L2 cache. Thus, we can attach a tag to each way in the L2 cache and send this tag information to the L1 cache when the data is loaded to the L1 cache. By doing so, for all the data in the L1 cache, we will know exactly the locations (i.e., ways) of their copies in the L2 cache. During the subsequent accesses when there is a write hit in the L1 cache (which also initiates a write access to the L2 cache under the write-through policy), we can access the L2 cache in an equivalent direct-mapping manner because the way tag of the data copy in the L2 cache is available. As this operation accounts for the majority of L2 cache accesses in most applications, the energy consumption of L2 cache can be reduced significantly. The basic idea of way-tagged cache was initially proposed in our past work [26] with some preliminary results. In this paper, 1063-8210/$26.00 © 2012 IEEE DAI AND WANG: ENERGY-EFFICIENT L2 CACHE ARCHITECTURE USING WAY TAG INFORMATION we extend this work by making the following contributions. First, a detailed VLSI architecture of the proposed way-tagged cache is developed, where various design issues regarding timing, control logic, operating mechanisms, and area overhead have been studied. Second, we demonstrate that the idea of way tagging can be extended to many existing low-power cache design techniques so that better tradeoffs of performance and energy efficiency can be achieved. Third, a detailed energy model is developed to quantify the effectiveness of the proposed technique. Finally, a comprehensive suite of simulations is performed with new results covering the effectiveness of the proposed technique under different cache configurations. It is also shown that the proposed technique can be integrated with existing low-power cache design techniques to further improve energy efficiency. The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In Section II, we provide a review of related low-power cache design techniques. In Section III, we present the proposed way-tagged cache. In Section IV, we discuss the detailed VLSI architecture of the way-tagged cache. Section V extends the idea of way tagging to existing cache design techniques to further improve energy efficiency. An energy model is presented in Section VI to study the effectiveness of the proposed technique. Simulation results are given in Section VII. II. RELATED WORK Many techniques have been developed to reduce cache power dissipation. In this section, we briefly review some existing work related to the proposed technique. In [16], Su et al. partitioned cache data arrays into subbanks. During each access, only the subbank containing the desired data is activated. Ghose et al. further divided cache bitlines into small segmentations [17]. When a memory cell is accessed, only the associated bitline segmentations are evaluated. By modifying the structure of cache systems, these techniques effectively reduce the energy per access without changing cache architectures. At the architecture level, most work focuses on set-associative caches due to their low miss rates. In conventional set-associative caches, all tag and data arrays are accessed simultaneously for performance consideration. This, however, comes at the cost of energy overhead. Many techniques have been proposed to reduce the energy consumption of set-associative caches. The basic idea is to activate fewer tag and data arrays during an access, so that cache power dissipation can be reduced. In the phased cache [18] proposed by Hasegawa et al., one cache access is divided into two phases. Cache tag arrays are accessed in the first phase while in the second phase only the data array corresponding to the matched tag, if any, is accessed. Energy consumption can be reduced because at most only one data array is accessed as compared to data arrays in a conventional -way set-associative cache. Due to the increase in access cycles, phased caches are usually employed in the lower level memory to minimize the performance impact. Another technique referred to as way concatenation was proposed by Zhang et al. [19] to reduce the cache energy in embedded systems. With the necessary software support, this cache can be configured as direct-mapping, two-way, or four-way set-associative according 103 to the system requirement. By accessing fewer tag and data arrays, better energy efficiency is attained. Although effective for embedded systems, this technique may not be suitable for high-performance general purpose microprocessors due to the induced performance overhead. Other techniques include way-predicting set-associative caches, proposed by Inoue et al. [20]–[22], that make a prediction on the ways of both tag and data arrays in which the desired date might be located. If the prediction is correct, only one way is accessed to complete the operation; otherwise, the rest ways of the cache are accessed to collect the desired data. Because of the improved energy efficiency, many way-prediction based techniques are employed in microprocessor designs. Another similar approach proposed by Min et al. [23] employs redundant cache (refer to as location cache) to predict the incoming cache references. The location cache needs to be trigged for every operation in the L1 cache (including both read and write assesses), which wastes energy if the hit rate of L1 cache is high. Among the above related work, phased caches and way-predicting caches are commonly used in high-performance microprocessors. Compared with these techniques, the proposed way-tagged cache achieves better energy efficiency with no performance degradation. Specifically, the basic idea of way-predicting caches is to keep a small number of the most recently used (MRU) addresses and make a prediction based on these stored addresses. Since L2 caches are usually unified caches, the MRU-based prediction has a poor prediction rate [24], [25], and mispredictions introduce performance degradation. In addition, applying way prediction to L2 caches introduces large overheads in timing and area [23]. For phased caches, the energy consumption of accessing tag arrays accounts for a significant portion of total L2 cache energy. As shown in Section V, applying the proposed technique of way tagging can reduce this energy consumption. Section VII-D provides more details comparing the proposed technique with these related work. III. WAY-TAGGED CACHE In this section, we propose a way-tagged cache that exploits the way information in L2 cache to improve energy efficiency. We consider a conventional set-associative cache system when the L1 data cache loads/writes data from/into the L2 cache, all ways in the L2 cache are activated simultaneously for performance consideration at the cost of energy overhead. In Section V, we will extend this technique to L2 caches with phased tag-data accesses. Fig. 1 illustrates the architecture of the two-level cache. Only the L1 data cache and L2 unified cache are shown as the L1 instruction cache only reads from the L2 cache. Under the writethrough policy, the L2 cache always maintains the most recent copy of the data. Thus, whenever a data is updated in the L1 cache, the L2 cache is updated with the same data as well. This results in an increase in the write accesses to the L2 cache and consequently more energy consumption. Here we examine some important properties of write-through caches through statistical characterization of cache accesses. Fig. 2 shows the simulation results of L2 cache accesses based 104 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON VERY LARGE SCALE INTEGRATION (VLSI) SYSTEMS, VOL. 21, NO. 1, JANUARY 2013 TABLE I EQUIVALENT L2 ACCESS MODES UNDER DIFFERENT OPERATIONS IN THE L1 CACHE Fig. 1. Illustration of the conventional two-level cache architecture. Fig. 2. Read and write accesses in the L2 cache running SPEC CPU2000 benchmarks. on the SPEC CPU2000 benchmarks [30]. These results are obtained from Simplescalar1 for the cache configuration given in Section VII-A. Unlike the L1 cache where read operations account for a large portion of total memory accesses, write operations are dominant in the L2 cache for all but three benchmarks (galgel, ammp, and art). This is because read accesses in the L2 cache are initiated by the read misses in the L1 cache, which typically occur much less frequently (the miss rate is less than 5% on average [27]). For galgel, ammp, and art, L1 read miss rates are high resulting in more read accesses than write accesses. Nevertheless, write accesses still account for about 20%–40% of the total accesses in the L2 cache. From the results in Section VII, each L2 read or write access consumes roughly the same amount of energy on average. Thus, reducing the energy consumption of L2 write accesses is an effective way for memory power management. As explained in the introduction, the locations (i.e., way tags) of L1 data copies in the L2 cache will not change until the data are evicted from the L2 cache. The proposed way-tagged cache exploits this fact to reduce the number of ways accessed during L2 cache accesses. When the L1 data cache loads a data from 1[Online]. Available: http://www.simplescalar.com/ the L2 cache, the way tag of the data in the L2 cache is also sent to the L1 cache and stored in a new set of way-tag arrays (see details of the implementation in Section IV). These way tags provide the key information for the subsequent write accesses to the L2 cache. In general, both write and read accesses in the L1 cache may need to access the L2 cache. These accesses lead to different operations in the proposed way-tagged cache, as summarized in Table I. Under the write-through policy, all write operations of the L1 cache need to access the L2 cache. In the case of a write hit in the L1 cache, only one way in the L2 cache will be activated because the way tag information of the L2 cache is available, i.e., from the way-tag arrays we can obtain the L2 way of the accessed data. While for a write miss in the L1 cache, the requested data is not stored in the L1 cache. As a result, its corresponding L2 way information is not available in the way-tag arrays. Therefore, all ways in the L2 cache need to be activated simultaneously. Since write hit/miss is not known a priori, the way-tag arrays need to be accessed simultaneously with all L1 write operations in order to avoid performance degradation. Note that the way-tag arrays are very small and the involved energy overhead can be easily compensated for (see Section VII). For L1 read operations, neither read hits nor misses need to access the way-tag arrays. This is because read hits do not need to access the L2 cache; while for read misses, the corresponding way tag information is not available in the way-tag arrays. As a result, all ways in the L2 cache are activated simultaneously under read misses. From Fig. 2 write accesses account for the majority of L2 cache accesses in most applications. In addition, write hits are dominant among all write operations. Therefore, by activating fewer ways in most of the L2 write accesses, the proposed waytagged cache is very effective in reducing memory energy consumption. Fig. 3 shows the system diagram of proposed way-tagged cache. We introduce several new components: way-tag arrays, way-tag buffer, way decoder, and way register, all shown in the dotted line. The way tags of each cache line in the L2 cache are maintained in the way-tag arrays, located with the L1 data cache. Note that write buffers are commonly employed in writethrough caches (and even in many write-back caches) to improve the performance. With a write buffer, the data to be written into the L1 cache is also sent to the write buffer. The operations stored in the write buffer are then sent to the L2 cache in sequence. This avoids write stalls when the processor waits for write operations to be completed in the L2 cache. In the proposed technique, we also need to send the way tags stored in the way-tag arrays to the L2 cache along with the operations in the write buffer. Thus, a small way-tag buffer is introduced to buffer the way tags read from the way-tag arrays. A way decoder is employed to decode way tags and generate the enable DAI AND WANG: ENERGY-EFFICIENT L2 CACHE ARCHITECTURE USING WAY TAG INFORMATION 105 Fig. 4. Way-tag arrays. Fig. 3. Proposed way-tagged cache. TABLE II OPERATIONS OF WAY-TAG ARRAYS signals for the L2 cache, which activate only the desired ways in the L2 cache. Each way in the L2 cache is encoded into a way tag. A way register stores way tags and provides this information to the way-tag arrays. IV. IMPLEMENTATION OF WAY-TAGGED CACHE In this section, we discuss the implementation of the proposed way-tagged cache. A. Way-Tag Arrays In the proposed way-tagged cache, each cache line in the L1 cache keeps its L2 way tag information in the corresponding entry of the way-tag arrays, as shown in Fig. 4, where only one L1 data array and the associated way-tag array are shown for simplicity. When a data is loaded from the L2 cache to the L1 cache, the way tag of the data is written into the way-tag array. At a later time when updating this data in the L1 data cache, the corresponding copy in the L2 cache needs to be updated as well under the write-through policy. The way tag stored in the way-tag array is read out and forwarded to the way-tag buffer (see Section IV-B) together with the data from the L1 data cache. Note that the data arrays in the L1 data cache and the way-tag arrays share the same address as the mapping between the two is exclusive. The write/read signal of way-tag arrays, WRITEH_W, is generated from the write/read signal of the data arrays in the L1 data cache as shown in Fig. 4. A control signal referred to as UPDATE is obtained from the cache controller. When the write access to the L1 data cache is caused by a L1 cache miss, UPDATE will be asserted and allow WRITEH_W to enable the write operation to the way-tag arrays ( , , see Table II). If a STORE instruction accesses the L1 data cache, UPDATE keeps invalid and WRITE_W indicates a read operation to the way-tag arrays ( , ). During the read operations of the L1 cache, the way-tag arrays do not need to be accessed and thus are deactivated to reduce energy overhead. To achieve this, the wordline selection signals generated by the decoder are disabled by WRITEH ( , ) through AND gates. The above operations are summarized in Table II. Note that the proposed technique does not change the cache replacement policy. When a cache line is evicted from the L2 cache, the status of the cache line changes to “invalid” to avoid future fetching and thus prevent cache coherence issues. A read or write operation to this cache line will lead to a miss, which can be handled by the proposed way-tagged cache (see Section III). Since way-tag arrays will be accessed only when a data is written into the L1 data cache (either when CPU updates a data in the L1 data cache or when a data is loaded from the L2 cache), they are not affected by cache misses. It is important to minimize the overhead of way-tag arrays. The size of a way-tag array can be expressed as (1) where , , and are the size of the L1 data cache, cache line size, and the number of ways in the L1 data cache, respectively. Each way in the L2 cache is represented by bits assuming the binary code is applied. As shown in (1), the overhead increases linearly with the size of L1 data cache and sublinearly with the number of ways in L2 cache . In addition, since is very small compared with (i.e., ), the overhead accounts for a very small portion of the L1 data cache. Clearly, the proposed technique shows good scalability trends with the increasing sizings of L1 and L2 caches. As an example, consider a two-level cache hierarchy where the L1 data cache and instruction cache are both 16 kB 2-way set-associative with cache line size of 32 B. The L2 cache is 4-way set-associative with 32 kB and each cache line has 64 106 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON VERY LARGE SCALE INTEGRATION (VLSI) SYSTEMS, VOL. 21, NO. 1, JANUARY 2013 Fig. 6. Timing diagram of way-tag buffer. Fig. 5. Way-tag buffer. B. Thus, 16 kB, 32 B, , and . The size of each way-tag array is 16 K 512 bits, and two way-tag arrays are needed for the L1 data cache. This introduces an overhead of only K of the L1 data cache, or K K K of the entire L1 and L2 caches. To avoid performance degradation, the way-tag arrays are operated in parallel with the L1 data cache. Due to their small size, the access delay is much smaller than that of the L1 cache. On the other hand, the way-tag arrays share the address lines with the L1 data cache. Therefore, the fan-out of address lines will increase slightly. This effect can be well-managed via careful floorplan and layout during the physical design. Thus, the way-tag arrays will not create new critical paths in the L1 cache. Note that accessing way-tag arrays will also introduce a small amount of energy overhead. However, the energy savings achieved by the proposed technique can offset this overhead, as shown in Section VII. B. Way-Tag Buffer Way-tag buffer temporarily stores the way tags read from the way-tag arrays. The implementation of the way-tag buffer is shown in Fig. 5. It has the same number of entries as the write buffer of the L2 cache and shares the control signals with it. Each entry of the way-tag buffer has bits, where is the line size of way-tag arrays. An additional status bit indicates whether the operation in the current entry is a write miss on the L1 data cache. When a write miss occurs, all the ways in the L2 cache need to be activated as the way information is not available. Otherwise, only the desired way is activated. The status bit is updated with the read operations of way-tag arrays at the same clock cycle. Similar to the write buffer of the L2 cache, the way-tag buffer has separate write and read logic in order to support parallel write and read operations. The write operations in the way-tag buffer always occur one clock cycle later than the corresponding write operations in the write buffer. This is because the write buffer, L1 cache, and way-tag arrays are all updated at the same clock cycle when a STORE instruction accesses the L1 data cache (see Fig. 4). Since the way tag to be sent to the way-tag buffer comes from the way-tag arrays, this tag will be written into the way-tag buffer one clock cycle later. Thus, the write signal of the way-tag buffer can be generated by delaying the write signal of the write buffer by one clock cycle, as shown in Fig. 5. The proposed way-tagged cache needs to send the operation stored in the write buffer along with its way tag to the L2 cache. This requires sending the data in the write buffer and its way tag in the way-tag buffer at the same time. However, simply using the same read signal for both the write buffer and the way-tag buffer might cause write/read conflicts in the way-tag buffer. This problem is shown in Fig. 6. Assume that at the th clock cycle an operation is stored into the write buffer while the way-tag buffer is empty. At the th clock cycle, a read signal is sent to the write buffer to get the operation while its way tag just starts to be written into the way-tag buffer. If the same read signal is used by the way-tag buffer, then read and write will target the same location of the way-tag buffer at the same time, causing a data hazard. One way to fix this problem is to insert one cycle delay to the write buffer. This, however, will introduce a performance penalty. In this paper, we propose to use a bypass multiplexer (MUX in Fig. 5) between the way-tag arrays and the L2 cache. If an operation in the write buffer is ready to be processed while the way-tag buffer is still empty, we bypass the way-tag buffer and send the way tag directly to the L2 cache. The EMPTY signal of the way-tag buffer is employed as the enable signal for read operations; i.e., when the way-tag buffer is empty, a read operation is not allowed. During normal operations, the write operation and the way tag will be written into the write buffer and way-tag buffer, respectively. Thus, when this write operation is ready to be sent to the L2 cache, the corresponding way tag is also available in the way-tag buffer, both of which can be sent together, as indicated by the th cycle in Fig. 6. With this bypass multiplexer, no performance overhead is incurred. C. Way Decoder The function of the way decoder is to decode way tags and activate only the desired ways in the L2 cache. As the binary code is employed, the line size of way-tag arrays is bits, where is the number of ways in the L2 cache. This minimizes the energy overhead from the additional wires and the impact on chip area is negligible. For a L2 write access caused by a write hit in the L1 cache, the way decoder works as a -to- decoder that selects just one way-enable signal. The technique proposed in [19] can be employed to utilize the way-enable signal to activate the corresponding way in the L2 cache. The way decoder DAI AND WANG: ENERGY-EFFICIENT L2 CACHE ARCHITECTURE USING WAY TAG INFORMATION 107 Fig. 7. Implementation of the way decoder. Fig. 8. Architecture of the WT-based phased access cache. operates simultaneously with the decoders of the tag and data arrays in the L2 cache. For a write miss or a read miss in the L1 cache, we need to assert all way-enable signals so that all ways in the L2 cache are activated. To achieve this, the way decoder can be implemented by the circuit shown in Fig. 7. Two signals, read and write miss, determine the operation mode of the way decoder. Signal read will be “1” when a read access is sent to the L2 cache. Signal write miss will be “1” if the write operation accessing the L2 cache is caused by a write miss in the L1 cache. Fig. 9. Operation modes of the WT-based phased access cache. D. Way Register The way register provides way tags for the way-tag arrays. For a 4-way L2 cache, labels “00”, “01”, “10”, and “11” are stored in the way register, each tagging one way in the L2 cache. When the L1 cache loads a data from the L2 cache, the corresponding way tag in the way register is sent to the way-tag arrays. With these new components, the proposed way-tagged cache operates under different modes during read and write operations (see Table I). Only the way containing the desired data is activated in the L2 cache for a write hit in the L1 cache, making the L2 cache equivalently a direct-mapping cache to reduce energy consumption without introducing performance overhead. V. APPLICATION OF WAY TAGGING ACCESS CACHES IN PHASED In this section, we will show that the idea of way tagging can be extended to other low-power cache design techniques such as the phased access cache [18]. Note that since the processor performance is less sensitive to the latency of L2 caches, many processors employ phased accesses of tag and data arrays in L2 caches to reduce energy consumption. By applying the idea of way tagging, further energy reduction can be achieved without introducing performance degradation. In phased caches, all ways in the cache tag arrays need to be activated to determine which way in the data arrays contains the desired data (as shown in the solid-line part of Fig. 8). In the past, the energy consumption of cache tag arrays has been ignored due to their relatively small sizes. Recently, Min et al. show that this energy consumption has become significant [33]. As high-performance microprocessors start to utilize longer addresses, cache tag arrays become larger. Also, high associativity is important for L2 caches in certain applications [34]. These factors lead to the higher energy consumption in accessing cache tag arrays [35]. Therefore, it has become important to reduce the energy consumption of cache tag arrays. The idea of way tagging can be applied to the tag arrays of phased access cache used as a L2 cache. Note that the tag arrays do not need to be accessed for a write hit in the L1 cache (as shown in the dotted-line part in Fig. 9). This is because the destination way of data arrays can be determined directly from the output of the way decoder shown in Fig. 7. Thus, by accessing fewer ways in the cache tag arrays, the energy consumption of phased access caches can be further reduced. Fig. 8 shows the architecture of the phased access L2 cache with way-tagging (WT) enhancement. The operation of this cache is summarized in Fig. 9. Multiplexor M1 is employed to generate the enable signal for the tag arrays of the L2 cache. When the status bit in the way-tag buffer indicates a write hit, M1 outputs “0” to disable all the ways in the tag arrays. As mentioned before, the destination way of the access can be obtained from the way decoder and thus no tag comparison is needed in this case. Multiplexor M2 chooses the output from the way decoder as the selection signal for the data arrays. If on the other hand the access is caused by a write miss or a read miss from the L1 cache, all ways are enabled by the tag array decoder, and the result of tag comparison is selected by M2 as the selection signal for the data arrays. Overall, fewer ways in the tag arrays are activated, thereby reducing the energy consumption of the phased access cache. Note that the phased access cache divides an access into two phases; thus, M2 is not on the critical path. Applying way tagging does not introduce performance overhead in comparison with the conventional phased cache. 108 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON VERY LARGE SCALE INTEGRATION (VLSI) SYSTEMS, VOL. 21, NO. 1, JANUARY 2013 VI. ENERGY MODEL To study the effectiveness of the proposed way-tagged cache, we utilize an energy model that describes the major components of cache energy consumption. In general, a cache system consists of address decoders and data multiplexers, which are shared by all ways. Each way contains several components such as tag arrays, data arrays, precharging circuit, way comparators, and sense amplifier circuit. Thus, the energy consumption per access of a conventional -way associative L2 cache can be expressed as (2) where , , and denote the energy consumption of address decoders, data multiplexers, and one way in the cache, respectively. Note that in the conventional L2 cache, all ways are activated during each access. Given the number of accesses , the total energy consumption can be determined as (3) Different from conventional caches, the proposed way-tagged cache activates different components depending on the type of cache accesses. As shown in Table I, if the access is caused by a read miss or a write miss in the L1 cache, the L2 cache works as a conventional cache, of which the energy consumption can be obtained from (2). On the other hand, if the access is caused by a write hit in the L1 cache, only one way in the L2 cache will be activated, of which the energy consumption is given by (4) Assuming the numbers of read misses, write misses, and write hits in the L1 cache are , , and , respectively, the energy consumption of the proposed way-tagged L2 cache can be expressed as way-tag buffer, way decoder and way register) are denoted as , , and , respectively. and are the numbers of write and read accesses, respectively, to the L2 cache. Since the proposed way-tagged cache does not affect the cache miss rate, the energy consumption related to cache misses such as replacement, off chip memory accesses and microprocessor stalls will be the same as that of the conventional cache. Therefore, we do not include these components in (5). Note that the energy components in (5) represent the switching power. Leakage power reduction is an important topic for our future study. We define the efficiency of the proposed way-tagged cache as (8) Substituting (2)–(7) into (8), we obtain (9) where (10) From (9), it is clear that the efficiency of the proposed waytagged cache is affected by a number of factors such as the number of ways in the L2 cache and the configuration of the L1 cache [e.g., size and the number of ways, which affect in (9)]. The impact of these factors will be evaluated in the next section. Note that in this paper we choose to evaluate the energy efficiency at the cache level as the proposed technique focuses exclusively on cache energy reduction. Smaller energy savings will be expected at the processor level because the L2 cache only consumes a portion of the total energy, e.g., around 12% in Pentium Pro CPU [31]. Reducing the total power of a processor that consists of different components (ALU, memory, busses, I/O, etc.) is an important research topic but is beyond the scope of this work. VII. EVALUATION AND DISCUSSION (5) In this section, we evaluate the proposed technique by comparing energy savings, area overhead, and performance with existing cache design techniques. where A. Simulation Setup Note that read hits in the L1 cache do not need to access the L2 cache and thus they are not included in (5). The energy overheads introduced by accessing (read and write) the way-tag arrays and other components (including the bypass multiplexer, We consider separate L1 instruction and data caches, both of 16 kB 4-way set-associative with cache line size of 64 B. The L2 cache is a unified 8-way set-associative cache with size of 512 kB and cache line size of 128 B. There are eight banks in the L2 cache. The L1 data cache utilizes the write-through policy and the L2 cache is inclusive. This cache configuration, used in Pentium-4 [23], will be used as a baseline system for comparison with the proposed technique under different cache configurations. (6) (7) DAI AND WANG: ENERGY-EFFICIENT L2 CACHE ARCHITECTURE USING WAY TAG INFORMATION 109 TABLE III ENERGY CONSUMPTION PER READ AND WRITE ACCESS OF THE CONVENTIONAL SET-ASSOCIATIVE L2 CACHE AND THE PROPOSED L2 CACHE In these simulations, Simplescalar1 is employed to obtain the cache access statistics and performance. The energy consumption is estimated by CACTI 5.32 for a 90-nm CMOS process. All the simulations are based on the SPEC CPU2000 benchmarks collected from the stream-based trace compression (SBC) [32], where trace files of 23 benchmarks are available. All the benchmarks were simulated for at least two billion memory references. B. Results of Baseline Cache Configuration 1) Energy Efficiency: Table III compares the average energy consumption of a read access and a write access in the conventional 8-way set-associative L2 cache and the proposed way-tagged L2 cache. Due to the fewer activated ways, the average energy consumption of the proposed way-tagged L2 cache is only about 12.9% of the conventional L2 cache during the write access under a write hit. Since the way-tag arrays are very small, they introduce only 0.01% energy overhead per read and write accesses. The energy overheads due to the way-tag buffer, bypass multiplexer, way decoder, and way register are much smaller and thus are not shown in Table III. Based on the cache access statistics obtained from Simplescalar, we estimate the values of , , , , and in (5). Employing (2)–(8), we can determine the energy efficiency of the proposed way-tagged cache. Fig. 10 shows that the energy reduction achieved by the proposed technique ranges from 83.4% (meas) to 13.1% (ammp) as compared to the conventional L2 cache. On average, the proposed technique can reduce 65.4% of the L2 energy consumption, or equivalently 7.5% of total processor power if applied in Pentium Pro CPU [31], where the L2 cache consumes about 12% of total processor power. These results demonstrate that by reducing the unnecessary way accesses in the L2 cache, our technique is very effective in reducing L2 cache power consumption. It is noted that the energy reduction achieved by the different applications is not uniform. This is because different applications have different write hit rates, which affect in (9) and in turn affect energy savings. 2) Area Overhead and Performance Impact: The area overhead of the proposed technique comes mainly from four components: way-tag arrays, way-tag buffer, bypass multiplexer, and way decoder. As discussed in Section IV, these components are very small. For example, the size of the way-tag arrays, the largest component, is only about 0.02% of the whole cache system. Also, only three additional wires are introduced for way 2[Online]. Available: http://www.hpl.hp.com/research/cacti/ Fig. 10. Energy reduction of the way-tagged L2 cache compared with the conventional set-associative L2 cache. tag delivery between the L1 and L2 caches. Thus, we expect the area overhead can be easily accommodated. The proposed way-tagged cache does not affect the hit rate, i.e., no performance degradation, as it does not change the cache placement policy. Furthermore, the way-tag arrays, way-tag buffer, and way decoder are operated in parallel with the L1 data cache, write buffer, and decoders of tag and data arrays in the L2 cache, respectively. Due to their small sizes, the access delay can be fully covered by the delay of the L1 data cache, i.e., no new critical paths are created. As a result, the proposed technique does not introduce any performance overhead at the architecture and circuit levels. C. Energy Reduction under Different Cache Configurations As discussed in Section VI, the effectiveness of the proposed technique varies with the configurations of L1 and L2 caches. In this subsection, we will study this effect by assessing the energy reduction achieved under different cache configurations in terms of the associativity and the sizes of L1 and L2 caches. Fig. 11 shows the energy reduction of the proposed technique for a 4-way set-associative L1 cache with cache sizes of 8, 16, and 32 kB, while the size of L2 cache is 512 kB. The block size in these L1 caches is 64 B while that of the L2 cache is 128 B. A larger energy reduction in the L2 cache is observed with the increase in the size of L1 cache. This is because by increasing the size of L1 cache, the miss rate will decrease which leads to a larger . This enables larger energy reduction according to (9). We also performed simulations by varying the size of the L2 cache from 256 to 1024 kB. Since the proposed technique does not target the misses in the L2 cache, changing L2 cache size has little effect on the relative energy reduction (i.e., both energy consumption and energy savings change proportionally). Fig. 12 shows the energy reduction under the 16 kB L1 cache and 512 kB L2 cache, where the number of ways in the L1 cache varies from 2, 4, to 8. The L2 cache is 8-way set-associative. It is shown that the proposed technique becomes more effective as the associativity of L1 cache increases. This comes from the fact that a higher associativity in general results in a smaller miss rate, which enables better energy efficiency in the L2 cache (i.e., more write hits and thus fewer accessed ways in the L2 cache). A similar trend can also be found in Fig. 13, which demonstrates 110 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON VERY LARGE SCALE INTEGRATION (VLSI) SYSTEMS, VOL. 21, NO. 1, JANUARY 2013 Fig. 11. Energy reduction of the way-tagged L2 cache compared with the conventional set-associative L2 cache under different L1 sizes. Fig. 14. Comparison of the MRU-based way-predicting cache and the proposed cache. Fig. 15. Energy reduction of the WT-based phased access L2 cache compared with the conventional phased access L2 cache. Fig. 12. Energy reduction of the way-tagged L2 cache compared with the conventional set-associative L2 cache under different L1 set associativity. D. Comparison With Existing Low-Power Cache Techniques Fig. 13. Energy reduction of the way-tagged L2 cache compared with the conventional set-associative L2 cache under different L2 set associativity. the effectiveness of the proposed technique for a 512 kB L2 cache with the associativity ranging from 4, 8, to 16, while the 16 kB L1 cache is 4-way associative. As the number of ways in the L2 cache increases, in (9) becomes larger and thus enables better energy efficiency. In other words, each time when there is a write hit in the L1 cache, only a small part of the L2 cache is activated as the number of ways in the L2 cache increases. In this subsection, we compare the proposed way-tagged cache with two existing low-power cache design techniques: phased access cache and MRU-based way-predicting cache. Figs. 14 and 15 show the energy reduction achieved by the three techniques for a 256 K 16-way set-associative L2 cache. It is shown that the proposed way-tagged cache is much more effective than the way-predicting cache in energy reduction. Specifically, our technique can achieve 32.6% more energy reduction on average. This is because the L2 cache is a unified cache, which in general leads to a poor prediction rate in the way-predicting cache. To compare with the phased cache, we employ the proposed WT-based phased access cache (see Section V) as it has the same number of access cycles as the phased cache. As shown in Fig. 15, the proposed technique achieves energy savings ranging from 45.1% to 8.1% with an average of 34.9% for the whole L2 cache at the same performance level. These results indicate that the energy consumption of tag arrays accounts for a significant portion of the total L2 cache energy. Thus, applying the technique of way tagging in the phased cache is quite effective. We also study the performance of these three cache design techniques. As discussed before, the proposed way-tagged cache in Section III has no performance degradation compared with the conventional set-associative L2 cache with simultaneous tag-data accesses. Using Simplescalar, we observed the DAI AND WANG: ENERGY-EFFICIENT L2 CACHE ARCHITECTURE USING WAY TAG INFORMATION performance degradation of the phased cache is very small for most applications, below 0.5% in terms of instruction per cycle (IPC). This is expected as L2 cache latency is not very critical to the processor performance. However, nontrivial performance degradation was observed in some applications. For example, benchmark perlbmk sees 3.7% decrease in IPC while the IPC of gzip decreases by 1.7%. The performance degradation may be more significant for other applications that are sensitive to L2 cache latency, such as TPC-C as indicated in [29]. As a result, L2 caches with simultaneous tag-data accesses are still preferred in some high-performance microprocessors [23], [28]. The similar trend was also observed in the way-predicting cache. VIII. CONCLUSION This paper presents a new energy-efficient cache technique for high-performance microprocessors employing the write-through policy. The proposed technique attaches a tag to each way in the L2 cache. This way tag is sent to the way-tag arrays in the L1 cache when the data is loaded from the L2 cache to the L1 cache. Utilizing the way tags stored in the way-tag arrays, the L2 cache can be accessed as a direct-mapping cache during the subsequent write hits, thereby reducing cache energy consumption. Simulation results demonstrate significantly reduction in cache energy consumption with minimal area overhead and no performance degradation. Furthermore, the idea of way tagging can be applied to many existing low-power cache techniques such as the phased access cache to further reduce cache energy consumption. Future work is being directed towards extending this technique to other levels of cache hierarchy and reducing the energy consumption of other cache operations. REFERENCES [1] G. Konstadinidis, K. Normoyle, S. Wong, S. Bhutani, H. Stuimer, T. Johnson, A. Smith, D. Cheung, F. Romano, S. Yu, S. Oh, V. Melamed, S. Narayanan, D. Bunsey, C. Khieu, K. J. Wu, R. Schmitt, A. Dumlao, M. Sutera, J. Chau, and K. J. Lin, “Implementation of a third-generation 1.1-GHz 64-bit microprocessor,” IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits, vol. 37, no. 11, pp. 1461–1469, Nov. 2002. [2] S. Rusu, J. Stinson, S. Tam, J. Leung, H. Muljono, and B. Cherkauer, “A 1.5-GHz 130-nm itanium 2 processor with 6-MB on-die L3 cache,” IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits, vol. 38, no. 11, pp. 1887–1895, Nov. 2003. [3] D. Wendell, J. Lin, P. Kaushik, S. Seshadri, A. Wang, V. Sundararaman, P. Wang, H. McIntyre, S. Kim, W. Hsu, H. Park, G. Levinsky, J. Lu, M. Chirania, R. Heald, and P. Lazar, “A 4 MB on-chip L2 cache for a 90 nm 1.6 GHz 64 bit SPARC microprocessor,” in IEEE Int. Solid-State Circuits Conf. (ISSCC) Dig. Tech. Papers, 2004, pp. 66–67. [4] S. Segars, “Low power design techniques for microprocessors,” in Proc. Int. Solid-State Circuits Conf. Tutorial, 2001, pp. 268–273. [5] A. Malik, B. Moyer, and D. Cermak, “A low power unified cache architecture providing power and performance flexibility,” in Proc. Int. Symp. Low Power Electron. Design, 2000, pp. 241–243. [6] D. Brooks, V. Tiwari, and M. Martonosi, “Wattch: A framework for architectural-level power analysis and optimizations,” in Proc. Int. Symp. Comput. Arch., 2000, pp. 83–94. [7] J. Maiz, S. hareland, K. Zhang, and P. Armstrong, “Characterization of multi-bit soft error events in advanced SRAMs,” in Proc. Int. Electron Devices Meeting, 2003, pp. 21.4.1–21.4.4. [8] K. Osada, K. Yamaguchi, and Y. Saitoh, “SRAM immunity to cosmic-ray-induced multierrors based on analysis of an induced parasitic bipolar effect,” IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits, pp. 827–833, 2004. 111 [9] F. X. Ruckerbauer and G. Georgakos, “Soft error rates in 65 nm SRAMs: Analysis of new phenomena,” in Proc. IEEE Int. On-Line Test. Symp., 2007, pp. 203–204. [10] G. H. Asadi, V. Sridharan, M. B. Tahoori, and D. Kaeli, “Balancing performance and reliability in the memory hierarchy,” in Proc. Int. Symp. Perform. Anal. Syst. Softw., 2005, pp. 269–279. [11] L. Li, V. Degalahal, N. Vijaykrishnan, M. Kandemir, and M. J. Irwin, “Soft error and energy consumption interactions: A data cache perspective,” in Proc. Int. Symp. Low Power Electron. Design, 2004, pp. 132–137. [12] X. Vera, J. Abella, A. Gonzalez, and R. Ronen, “Reducing soft error vulnerability of data caches,” presented at the Workshop System Effects Logic Soft Errors, Austin, TX, 2007. [13] P. Kongetira, K. Aingaran, and K. Olukotun, “Niagara: A 32-way multithreaded Sparc processor,” IEEE Micro, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 21–29, Mar. 2005. [14] J. Mitchell, D. Henderson, and G. Ahrens, “IBM POWER5 processor-based servers: A highly available design for business-critical applications,” IBM, Armonk, NY, White Paper, 2005. [Online]. Available: http://www03.ibm.com/systems/p/hardware/whitepapers/power5_ras.pdf [15] N. Quach, “High availability and reliability in the Itanium processor,” IEEE Micro, pp. 61–69, 2000. [16] C. Su and A. Despain, “Cache design tradeoffs for power and performance optimization: A case study,” in Proc. Int. Symp. Low Power Electron. Design, 1997, pp. 63–68. [17] K. Ghose and M. B. Kamble, “Reducing power in superscalar processor caches using subbanking, multiple line buffers and bit-line segmentation,” in Proc. Int. Symp. Low Power Electron. Design, 1999, pp. 70–75. [18] A. Hasegawa, I. Kawasaki, K. Yamada, S. Yoshioka, S. Kawasaki, and P. Biswas, “Sh3: High code density, low power,” IEEE Micro, vol. 15, no. 6, pp. 11–19, Dec. 1995. [19] C. Zhang, F. Vahid, and W. Najjar, “A highly-configurable cache architecture for embedded systems,” in Proc. Int. Symp. Comput. Arch., 2003, pp. 136–146. [20] K. Inoue, T. Ishihara, and K. Murakami, “Way-predicting set-associative cache for high performance and low energy consumption,” in Proc. Int. Symp. Low Power Electron. Design, 1999, pp. 273–275. [21] A. Ma, M. Zhang, and K. Asanovi, “Way memoization to reduce fetch energy in instruction caches,” in Proc. ISCA Workshop Complexity Effective Design, 2001, pp. 1–9. [22] T. Ishihara and F. Fallah, “A way memoization technique for reducing power consumption of caches in application specific integrated processors,” in Proc. Design Autom. Test Euro. Conf., 2005, pp. 358–363. [23] R. Min, W. Jone, and Y. Hu, “Location cache: A low-power L2 cache system,” in Proc. Int. Symp. Low Power Electron. Design, 2004, pp. 120–125. [24] B. Calder, D. Grunwald, and J Emer, “Predictive sequential associative cache,” in Proc. 2nd IEEE Symp. High-Perform. Comput. Arch., 1996, pp. 244–254. [25] T. N. Vijaykumar, “Reactive-associative caches,” in Proc. Int. Conf. Parallel Arch. Compiler Tech., 2011, p. 4961. [26] J. Dai and L. Wang, “Way-tagged cache: An energy efficient L2 cache architecture under write through policy,” in Proc. Int. Symp. Low Power Electron. Design, 2009, pp. 159–164. [27] L. Hennessey and D. A. Patterson, Computer Architecture: A Quantitative Approach, 4th ed. New York: Elsevier Science & Technology Books, 2006. [28] B. Brock and M. Exerman, “Cache Latencies of the PowerPC MPC7451,” Freescale Semiconductor, Austin, TX, 2006. [Online]. Available: cache.freescale.com [29] T. Lyon, E. Delano, C. McNairy, and D. Mulla, “Data cache design considerations for Itanium 2 processor,” in Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Comput. Design, 2002, pp. 356–362. [30] Standard Performance Evaluation Corporation, Gainesville, VA, “SPEC CPU2000,” 2006. [Online]. Available: http://www.spec. org/cpu [31] “Pentium Pro Family Developer’s Manual,” Intel, Santa Clara, CA, 1996. [32] A. Milenkovic and M. Milenkovic, “Exploiting streams in instruction and data address trace compression,” in Proc. IEEE 6th Annu. Workshop Workload Characterization, 2003, pp. 99–107. [33] R. Min, W. Jone, and Y. Hu, “Phased tag cache: An efficient low power cache system,” in Proc. Int. Symp. Circuits Syst., 2004, pp. 23–26. 112 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON VERY LARGE SCALE INTEGRATION (VLSI) SYSTEMS, VOL. 21, NO. 1, JANUARY 2013 [34] M. K. Qureshi, D. Thompson, and Y. N. Patt, “The V-way cache: Demand based associativity via global replacement,” in Proc. Int. Symp. Comput. Arch., 2005, pp. 544–555. [35] J. M. Rabaey, Digital Integrated Circuits: A Design Perspective. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1996. Jianwei Dai received the B.S. degree from Beijing University of Chemical Technology, Beijing, China, in 2002, the M.Eng. degree from Beihang University, Beihang, China, in 2005, and the Ph.D. degree from the University of Connecticut, Storrs, in 2011. Currently, he is with Intel Corporation, Hillsboro, OR, where he is participating in designing next generation processors. His research interests include low power VLSI design, error and reliability-centric statistical modeling for emerging technology, and nanocomputing. Lei Wang (M’01–SM’11) received the B.Eng. degree and the M.Eng. degree from Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, in 1992 and 1996, respectively, and the Ph.D. degree from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, iUrbana-Champaign, in 2001. During the Summer of 1999, he worked with Microprocessor Research Laboratories, Intel Corporation, Hillsboro, OR, where his work involved development of high-speed and noise-tolerant VLSI circuits and design methodologies. From December 2001 to July 2004, he was with Microprocessor Technology Laboratories, Hewlett-Packard Company, Fort Collins, CO, where he participated in the design of the first dual-core multi-threaded Itanium Architecture Processor, a joint project between Intel and Hewlett-Packard. Since August 2004, he has been with the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Connecticut, where he is presently an Associate Professor. Dr. Wang was a recipient of the National Science Foundation CAREER Award in 2010. He is a member of IEEE Signal Processing Society Technical Committee on Design and Implementation of Signal Processing Systems. He currently serves as an Associate Editor for the IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTERS. He has served on Technical Program Committees of various international conferences.