Electronic monitoring in practice: the second year of the trials of

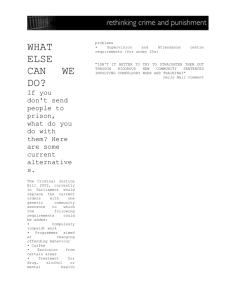

advertisement