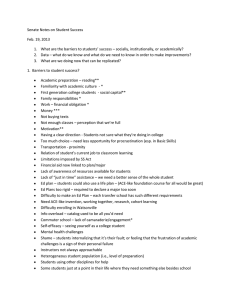

Factors Associated With Retention Rates in Career and

advertisement