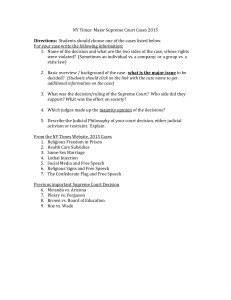

Understanding United States v. Windsor and the Symposium

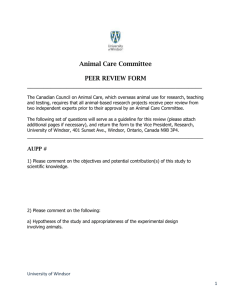

advertisement