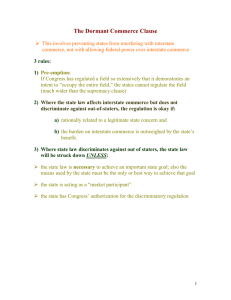

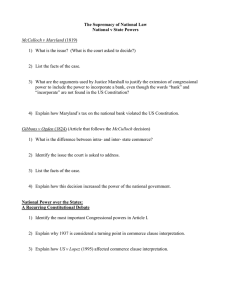

The Commerce Clause and Executive Power

advertisement