SECTORAL OUTLOOK 2013-2015

NOVA SCOTIA

Winter 2014

Page |2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................................................. 3

LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................................... 3

LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................................................... 3

ABOUT THE SECTORAL OUTLOOK ......................................................................................................... 4

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................. 5

NOTES ON METHODOLOGY ...................................................................................................................... 6

SECTION 1: ECONOMIC AND LABOUR MARKET OVERVIEW ............................................................... 7

SECTION 2: SECTORAL OUTLOOK 2013-2015 ...................................................................................... 15

CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................................................ 26

ANNEX 1 ..................................................................................................................................................... 27

REFERENCES ............................................................................................................................................ 29

Page |3

Acronyms

COPS………………….Canadian Occupational Projection System

EU…………………..….European Union

GDP……………………Gross Domestic Product

HST…………………….Harmonized Sales Tax

LFS………………….....Labour Force Survey, Statistics Canada

NAICS…………………North American Industrial Classification System

NHS……………………National Household Survey, Statistics Canada

NL……………………...Newfoundland and Labrador

NS……………………...Nova Scotia

PEI……………………...Prince Edward Island

ROOC………………….Regional Occupational Outlooks in Canada

US………………………United States

List of Figures

Figure 1:

Figure 2:

Figure 3:

Figure 4:

Figure 5:

Figure 6:

Figure 7:

Figure 8:

Figure 9:

Figure 10:

Figure 11:

Figure 12:

Figure 13:

Comparison of Employment Growth, Atlantic and Canada. …………..9

Estimates of Interprovincial Migrants, Atlantic 2012-13.……………....10

Distribution of Employment Growth, NS 2013-1015……………….…..17

Health Care Employment, NS 2000-2015.………………………….…..19

Professional, Scientific, & Technical Services, NS 2000-2015…….....19

Mining, Oil & Gas Employment, NS 2000-2015.…………….…….…...20

Finance, Insurance, Real Estate Employment, NS 2000-2015.………20

Accommodation & Food Employment, NS 2000-2015 …………….....21

Manufacturing Employment, NS 2000-2015 ………….………………..21

Other Services Employment, NS 2000-2015 ……………………….….22

Construction Employment, NS 2000-2015 ……………………………..22

Trade Employment, NS 2000-2015 ……………………………………..23

Public Administration Employment, NS 2000-2015 …….……….........23

List of Tables

Table 1:

Table 2:

Table 3:

Labour Market Indicators, Atlantic Canada 2010-2012……….……...11

Labour Market Indicators, Nova Scotia 2010-2012…………………..13

Nova Scotia Industrial Outlook …………………………………….…..18

Page |4

About the Sectoral Outlook

Each year, Service Canada issues three-year employment forecasts both by industry and by

occupation for Nova Scotia as a whole. The results of the analysis are published in the form of a

report intended to provide a comprehensive overview of recent labour market developments and

outlooks in Nova Scotia.

We hope this series of documents will interest people who are seeking labour market guidance

and those who help them, including parents, educational staff, and employment assistance

services workers. It should also interest businesses and employer associations that want to

identify human resources management issues in their industries.

This document is composed of two sections. The first part provides a synopsis of the labour

market in the region, including an overview of economic developments and key labour market

indicators. The second part presents sectoral outlooks by industrial groups catalogued

according to the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS).

Finally, we would like to acknowledge the LMI team located in National Headquarters who

provided the forecasting tool and ongoing support throughout this project and the Canadian

Occupational Projection System (COPS) team who provided us with access to many of the base

analysis for the forecasting tool used to carry out this study. We also wish to acknowledge the

contribution of provincial colleagues in the validation of the employment estimates

Page |5

Executive Summary

The Nova Scotia economy has been constrained over the most recent years and is expected to

remain so over the forecast period 2013-2015. One of the largest challenges to the province is

that of a slow growth in the population, which has decelerated significantly over the last decade.

This has resulted in an aging population in the province, a condition that has been exacerbated

by a recent large outflow of younger migrants from the province.

The labour market in the province has been challenged over the most recent years and is

expected to continue to perform weakly until 2015. Employment has been fairly stagnant over

the last several years and is expected to grow slowly over the forecast period. The labour force

in the province has not grown significantly since 2010 which, coupled with weak employment

growth, has resulted in relatively high levels of unemployment in the province. The

unemployment rate in 2012 was a noticeable increase from the recent low evident in 2008 and

is not expected to diminish significantly over the forecast period.

Nova Scotia has emerged as a predominately service sector economy in terms of employment

and is expected to continue to do so over the forecast period. Demographic change has helped

push Health services to the front in terms of current and future employment growth. A shift

towards technology and knowledge intensive industries will continue to increase employment in

Professional, Scientific and Technical Services. A rebound in offshore oil activity and mining

should lead to a modest increase in Mining and Oil and Gas in Nova Scotia. Employment

growth is also expected for Finance, Insurance and Real Estate and Accommodation and Food

Services as the economy slowly improves.

The economy and labour market is expected to get a significant boost from the shipyard work

that will be undertaken at the Irving Shipyard; however the production of the ships is not

expected will to begin until late 2015 and will be largely outside this forecast.

Employment is expected to contract for Construction in the province due to low levels of major

project activity and weakness in residential housing. The restrained economy is also anticipated

to be reflected in the deterioration of Trade employment in the province, and public budgetary

restraint will be reflected in a contraction in employment in Public Administration in the province.

Page |6

Notes on Methodology

The three-year employment outlook model produces medium-term industrial and occupational

employment projections at the provincial and sub-provincial level. The projection model is based

on an economic environmental analysis to establish a common and coherent analytic framework

as the basis for developing the detailed employment forecasts. Specifically, this framework is

based on the Canadian Occupational Projection System (COPS) macro-economic scenario

supported by forecasts produced by the Conference Board of Canada. The labour market

scenario makes it possible to better characterize labour market conditions expected to prevail

during the review period.

Once the macro-economic scenario is established, employment by industry forecast estimates

are generated by the Canadian Occupational Projection System (COPS) partnership and

supported by the Conference Board of Canada. These forecast estimates are then validated by

regional economists. The validation process is a two-step approach employing an analytical

validation using supplementary variables, as well as a consultative process with key partners

and stakeholders.

In the Atlantic region, three-year employment forecasts are produced based on the analysis

described above for the three-year period, from 2013 to 2015. The results are presented at a

broad aggregate level based on the two-digit North American Industry Classification System

(NAICS) to ensure better reliability of the estimates. Precise definitions of the industries are

available in the NAICS published by Statistics Canada. This level of aggregation is based on the

Labour Force Survey industry tables (16 industries) released by Statistics Canada for the

Atlantic Provinces each month. The only variation is the separation of the Mining and Oil and

Gas industry from Forestry, Fishing and Hunting due to its relative importance in the region.

Those industries with a positive or negative employment growth of 150 or greater over the

forecast period were considered to be showing significant growth and were analyzed in more

depth. The remaining sectors were deemed relatively stable or too small to discuss any

changes with adequate reliability.

The annual average growth rates in the tables are calculated using compound growth rates.

The growth rates specifically refer to changes from 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 with 2013 as the

base year.

Page |7

Section 1: Economic and Labour Market Overview

The first section sets the context for the employment projections by providing a synopsis of the

global economic situation, recent trends in the Canadian economy, and the economic and

labour market situation in Atlantic Canada as well as in Nova Scotia.

The Global Economic Environment

The global economy slowed for the second consecutive year in 2012 as weak growth among

developed countries, including the United States (US), continued to take its toll. Coming into

2013 there was general optimism that conditions would improve during the second half of the

year, but the upturn is now projected to occur later in 2014. In October 2013, the International

Monetary Fund (IMF) lowered its 2013 global economic expansion target to 2.9%, which

translates into a third straight year of slowing world growth.

The US is the world’s largest economy, responsible for over 18% of global GDP in 2012.

However, China could take over the top spot as early as 2016, according to the latest IMF

forecast. Not surprisingly, the two economies are closely linked, and China is feeling the effect

of slow growth in a number of its large export markets, including the US. In fact, China’s

expansion has slowed to about 7.5% per year. While this rate of growth seems enormous by

western standards, it represents China's worst performance in 23 years.

Keeping a steady pace of growth is a challenge for the US economy. Following two relatively

slow years, the economy expanded by 2.2% in 2012, and this was the highest rate among G7

countries. US growth slowed in the first half of 2013, and the IMF now anticipates 1.6% total

growth for the year. Yet there is widespread optimism that the US will drive much of the global

growth in 2014. According to the October 2013 US Economic Forecast, growth will begin to

accelerate in the middle of 2014 and will continue in 2015 and 2016. This positive outlook is

echoed by the IMF, which forecasts 2.6% GDP growth in the US in 2014

Meanwhile, Germany, France, Italy, Spain, and other European Union (EU) member states

continue to struggle to get out of the recession. With GDP having receded by 0.4% in 2012, the

EU is expected to shrink an additional 0.4% in 2013 according to the IMF. The effects of the

sovereign debt crisis have varied throughout the EU, and the most troubled EU member states

continue to suffer through on-going austerity measures. However, business confidence

indicators (inflation, interest rates, foreign investment, etc.) suggest economic activity is close to

stabilizing for some EU members.

Page |8

The Canadian Environment

Canada’s economy outperformed those of most other developed nations in 2012, posting real

GDP growth of 1.8% over the year. While the country may have done well compared to other

developed countries, on its own merits, economic performance in 2012 has to be considered

mediocre. Long term, Canada needs GDP growth of between 2.0% and 2.5% in order for

Canadians to maintain their standard of living.

As with the world economy, Canada’s economic activity was widely expected to pick up during

the second half of 2013. The Bank of Canada has since lowered its outlook due to reduced

contributions from net exports and business investment. As of late October 2013, the Bank of

Canada called for the economy to grow by 1.6% in 2013, 2.3% in 2014, and 2.6% in 2015, with

commodity-rich Alberta, Saskatchewan, and NL playing lead roles in the country’s economic

growth.

The central bank had expected exports to show an increase in the third quarter of 2013, but

weakened global demand and fiscal challenges within the US market delayed this turnaround.

However, stronger US economic growth and a weaker Canadian dollar are expected to propel

export gains.

In response to slow economic growth and low inflation, the Bank of Canada is likely to hold

interest rates around 1% through 2015. This measure could potentially reignite the housing

market, increase borrowing, and accelerate growth, particularly in the critical export sector.

International trade makes up a large part of the Canadian economy, accounting for more than

45% of GDP. In 2012 the US, EU, and China were the top three destinations for Canadian

exports, together accounting for almost 90% of the value of all exports. The US, by far Canada’s

largest trading partner, is typically the destination for three-quarters of the value of Canadian

exported goods. In 2012 the EU received 8.5% of Canadian shipments and China about half

that. Between 2008 and 2012, China displaced Japan as Canada’s third largest export market.

Given the increasingly uncertain prospects for Canada’s largest trading partner, it seems

reasonable to expect modest export growth in 2013 and 2014. Although Canadian businesses

have generally welcomed the tentative Canada – EU trade deal, which was agreed to in 2013, it

will be at least two years before the deal is implemented and begins to impact export volumes.

Through the first eight months of 2013, Canada’s leading exports to:

the US were: energy products, including oil & gas and electrical power; motor vehicles and

parts; and wood, lumber, and pulp and paper products;

Page |9

the EU were: precious stones and metals, including gold and diamonds; aircraft and parts;

and crude and petroleum oils; and

China were: wood, lumber, and pulp and paper products; seed and food oils, grains, and

legumes; and iron and copper ores.

The Economy in Atlantic Canada

Since the 1950s, population growth has been slower in Atlantic Canada compared to the rest of

the country. According to Statistics Canada’s National Household Survey (NHS) results, in 2011

Atlantic Canada's population was 2,327,640, representing a 2% increase from the 2006

Census. Comparatively, the population of Canada grew at a faster rate of 6% during this period.

The gender composition of Atlantic Canada’s population was similar to the rest of country, as

males and females were fairly evenly distributed. Atlantic Canada has an older population than

the rest of the country with a median age ranging from 42.8 years in PEI to 44 years in NL,

compared to 40.6 years for all of Canada.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Atlantic

Canada’s labour force and employment

Figure 1: Comparison of Employment Growth

grew at a similar pace than the rest of

(%)

Canada

Atlantic

Canada. There was, however, a

2.5

2.0

significant divergence between national

1.8

2.0

1.6

and regional trends that emerged

1.4

1.5

during the recession of the 1990s.

1.0

1.0

1.0

Between 1998 and 2008, employment

0.6

0.6

growth outpaced labour force growth in

0.5

the Atlantic. As a result, unemployment

0.0

rates declined in the region, reaching

1980s

1990s

2000s

2010s

an all-time low of 9.1% in 2007,

narrowing the gap with Canada. During

Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey

this period, several large energy

projects occurred, including offshore oil & gas developments, acting as a catalyst for growth in

many sectors of the Atlantic economy.

Since the 2009 global recession, employment levels have declined for all major age groups in

the region, except for older workers (those aged 55 years and over). The employment share of

this age group has increased and has now surpassed the proportion of youth (15-24 years)

employed in the Atlantic region. Older workers (55 yrs.+) currently account for 21% of total

employment, the highest share on record. Youth (15-24 years) account for only 13%, the lowest

employment share for this age group since 1976. The prime working-age group (25-54 years)

account for 65% of total employment. The employment share of this age cohort has steadily

been in decline since reaching an all-time high of 76% in 1999.

P a g e | 10

Figure 2: Estimates of Interprovincial Migrants

(July 2012 – June 2013)

In

30000

Out

Net

21542

20000

10000

14717

15665

9972

9097

11850

4220

3146

0

-10000

NL

-875

PE

-1074

NS

-5877

NB

-2867

As shown in Figure 2, as of June 30, 2013, net

interprovincial migration was negative in all

provinces in the Atlantic and was at a six-year

low. According to Statistics Canada annual

demographic estimates, about 38,812 people

left the Atlantic region for other parts of the

country between July 2012 and June 2013,

and only 27,926 people moved to the Atlantic

region from other provinces over the same

period.

Source: Statistics Canada, Annual Demographic Estimates

This resulted in a net outflow of 10,886 people from the Atlantic region over the past year. NS

experienced the largest interprovincial net outflow (-5,658) to other parts of the country,

accounting for about 52% of those who left the Atlantic region.

Ontario and Alberta remain the top provinces of destination for the vast majority of Atlantic

Canadians. Between 2000 and 2013, approximately 77% of people who migrated out of the

Atlantic chose these two provinces as their destination of choice. Data shows that an increasing

share of Atlantic Canadians, however, are choosing Manitoba and Saskatchewan as their

province of destination with an increase of 26% since 2011.

Youth aged 20-34 are the most likely group to migrate away from the Atlantic region. In 20122013, just over 5,500 youth left the region for other areas of the country. One of the main

incentives for interprovincial migration is for economic reasons as buoyant labour markets

increase an individual’s chances of gaining employment. Individuals with more education are, in

general, more likely to leave the Atlantic region for more prosperous provinces.

In Atlantic Canada, both the size of the labour force and employment levels increased from

2011 to 2012, but the labour force grew at a faster rate than employment. As a result, the

unemployment rate increased slightly to 10.3%. Nationally, the unemployment rate edged down

to 7.2% during the same period. The high unemployment rate in Atlantic Canada can largely be

explained by higher unemployment in the rural areas. In 2012, the unemployment rate in the

region’s urban core was 7.8% compared to 14.6% in rural areas. The high unemployment rate

in rural Atlantic Canada reflects the highly seasonal nature of the rural economies in the region,

which results in large seasonal variation in employment.

P a g e | 11

Table 1: Atlantic Canada Labour Market Indicators, 2010 – 2012

2010

2011

2012

(000s)

2010-2011

Change

2011-2012

Change

Number

%

Number

%

Population 15+ (‘000)

1938.9

1946.5

1948.9

7.6

0.4

2.4

0.1

Labour Force (‘000)

1227.1

1225.0

1237.1

-2.1

-0.2

12.1

1.0

Employment (‘000)

1098.6

1102.2

1110.2

3.6

0.3

8.0

0.7

Full-time (‘000)

912.2

914.3

921.6

2.1

0.2

7.3

0.8

Part-time (‘000)

186.4

188.0

188.8

1.6

0.9

0.8

0.4

Unemployment (‘000)

128.5

122.8

127.0

-5.7

-4.4

4.2

3.4

Unemployment Rate

10.5

10.0

10.3

-0.4

-

0.2

-

Participation Rate

63.3

62.9

63.5

-0.4

-

0.5

-

Employment Rate

56.7

56.6

57.0

0.0

-

0.3

-

Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey

The service sector has continued to be the largest sector of employment in Atlantic Canada,

accounting for 79% of total employment. However, since the 2009 economic recession, job

growth in this sector has slowed to only 0.7% compared to an average of 1.0% between 2003

and 2008. The Trade industry, which is a very significant component of the service sector in

Atlantic Canada in terms of employment, has begun to recover from some of the job losses

recorded in 2012. There were also notable gains in Business Services, Health Care, and

Information and Cultural industries. However, the gains were not enough to completely offset

job losses in other industries including significant losses in Financial Services, Education, and

Other Services.

Jobs in the Goods-producing sector have been on the decline overall in the Atlantic region in

recent years. Employment declined by 3,600 (or 1.6%) in the Goods-producing sector in 2012

compared to the previous year. This was due to job losses in Manufacturing, Construction, and

resources industries (with the exception of the Mining, Oil & Gas sector). However, industrial

restructuring, especially in the rural areas, has led to the closure of several plants resulting in

notable job losses recently. This trend continues to dampen employment growth in

Manufacturing and other related primary industries.

P a g e | 12

The Nova Scotia Economy

The Nova Scotia economy has been constrained over the most recent years and is expected to

remain so over the forecast period. Provincial real GDP grew only marginally in 2012 (0.2%)

and well below 1% in 2013 (0.8%). GDP growth is expected to accelerate to close to 2% in 2014

and strengthen into 2015.

Although exports have been challenged over the last years, there has been a general upswing

in export activity as the US economy improves. In particular, export activity has increased in

2013 for paper products with the reopening of the NewPage mill, and significant increases were

also recorded for forestry and building products, rubber and plastics, and farm and fish products

(NS DOF). The recovery in exports should be supported by a general weakening of the

Canadian dollar versus that of the United States over the forecast period.

On a domestic front, a significant challenge to the economy will be the continued weakness in

Construction in the province. In Nova Scotia, the seasonally adjusted annual rate of housing

starts was 2,520 in January 2014, which was a significant decline from 7,776 in January 2013.

The weakness is primarily in single unit residential construction and has been offset to a degree

by multiple unit housing starts which are concentrated in the Halifax Metropolitan area. A

brighter note is expected over the forecast period for investment in non-residential construction,

which is anticipated to rebound as major projects begin to commence in the province. APEC

anticipates an increase in major project investment of 12% in 2014, and this should remain

strong into 2015 as projects such as the shipbuilding activity at the Irving yard begin production

and offshore energy activity rebounds.

The general improvement in the provincial economy should manifest in an improvement in retail

sales in the province. Retail sales grew by roughly 1% in 2012, mostly supported by motor

vehicle sales. Retail sales are expected to strengthen considerably in 2013 as interest rates

remain low, inflation remains stable, and economic activity rebounds. Retail sales are expected

to remain in the vicinity of 2% growth in 2014 and 2015.

The drop in the exchange rate, an improving US economy, and resumption of the ferry service

to the US from Yarmouth should help to improve Tourism in the province over the 2013-2015

period. The Tourism industry in the province is significant – it is valued at $2 billion and

contributes $722 million to provincial gross domestic product, or about 2% of all provincial

economic activity. It has a direct employment impact of over 24,000 jobs, with many

concentrated in Accommodation and Food Services.

The labour market in Nova Scotia has been constrained over the last three years. Growth in the

working-age population has decelerated significantly over the last decade and has grown by just

over 1% last year, as compared to 5% at the beginning of the decade. The slowing population

P a g e | 13

growth is the result of a decreasing birth rate in the province and recently accelerated out

migration from the area. Initial estimates for 2012-13 indicate a record net flow of almost 5,600

from the province, most of whom are relatively young. This has resulted in a slowly growing and

rapidly aging source population in Nova Scotia.

Table 2: Nova Scotia Labour Market Indicators, 2010 – 2012

2010

Population 15+ (‘000)

2011

(000s)

2010-2011

Change

2012

2011-2012

Change

Number

%

Number

%

777

779.1

780.3

2.1

0.3

1.2

0.2

Labour Force (‘000)

498.8

496.6

500.4

-2.2

-0.4

3.8

0.8

Employment (‘000)

452.5

452.8

455.5

0.3

0.1

2.7

0.6

Full-time (‘000)

365.7

367.3

366.3

1.6

0.4

-1.0

-0.3

Part-time (‘000)

86.8

85.5

89.3

-1.3

-1.5

3.8

4.4

Unemployment (‘000)

46.3

43.8

44.9

-2.5

-5.4

1.1

2.5

Unemployment Rate

9.3

8.8

9

-0.5

-

0.2

Participation Rate

64.2

63.7

64.1

-0.5

-

0.4

Employment Rate

58.2

58.1

58.4

-0.1

0.3

Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey

Mirroring the slowdown in the population growth, the labour force in Nova Scotia has not

changed significantly in the last three years. The change in the labour force has been well under

1% over this period, a noticeable slowdown since the beginning of the decade.

The labour force participation rate in the province has remained relatively flat since the middle of

the last decade, hovering around 64%. This is noticeably below the national average of roughly

67% over the same period. The lower participation rate reflects a number of factors, including

an older population who tend to have lower levels of labour force participation.

Employment in the province has been similarly stagnant since 2008. There has been no

significant growth in employment during this period, with employment in 2012 being only 1%

greater than four years ago. Interestingly, the employment increase, while marginal, was entirely

in part-time work. Full-time employment actually fell over the same period.

P a g e | 14

One aspect of employment that is worth mentioning is the rise in the number of older workers in

the province. Since at least the middle of this decade, most of the employment growth in the

Nova Scotia labour market has been in older workers aged 55 years and over. In 2012 alone,

employment increased for older workers (55yrs+) by 7,500 while employment decreased by

over 4,500 for the younger age groups.

With a stagnant labour market and weak employment levels, the number of unemployed in the

province has not declined but has actually grown since bottoming out in the middle of the

decade. This was mirrored with a steady increase in the unemployment rate over the last four

years, rising from 7.7% in 2008 to 9.0% in 2012.

P a g e | 15

Section 2: Sectoral Outlook 2013-2015

This section provides an overview of the industrial structure in Nova Scotia, followed by a

synopsis of expected changes in the industrial base over the forecast period. The latter part of

Section 2 provides more detailed analysis of industries projected to grow, industries projected to

decline, and industries perceived to remain relatively stable over the next three years.

Industrial Structure

Nova Scotia has traditionally been a producer of primary products, particularly the exportation of

fish, and forestry-related products. However, the provincial economy and labour market have

continued to undergo a profound transformation, as services increasingly emerge as the

predominant source of employment in Nova Scotia. Supporting this new trend is a heavy

reliance on employment in the public sector in the province, particularly in Halifax. For example,

the proportion of Federal government employment in the province is a full percentage point

higher than the national average. This data does not include the relatively large presence of the

military which is centred in the Halifax Metropolitan area.

Service employment now accounts for over 80% of employment in the province, which is above

the national average of 78%. This share has increased noticeably in 20 years. In 1992 the share

of services in provincial employment was roughly three quarters.

In terms of specific service sectors, perhaps the most fundamental impact on increased demand

for services has been brought forth by an aging population in the province. In particular, the

demand for Health services has increased dramatically in the province. As a reflection of this,

Health employment has increased from 12% to 15% of provincial employment in two decades,

and accounted for almost one-third of the employment increase over the 20-year period.

Growth in other service-related sectors is also worthy of noting in the province. As part of a

collaborative development strategy, an industry emerged that centred on the provision of

information services through contact (call) centers in the province. Employment in Business

Services, of which contact centres are an important part, grew rapidly in the province from

minimal levels to over 15,000 employees in the past decade. Although this industry has

contracted in recent years due to the high dollar and international competition, it still remains a

significant part of the service economy in the province.

Another aspect of the continued growth of employment in the Services-producing sector is the

expansion of knowledge intensive industries in the province, particularly those found in

Professional, Scientific and Technical Services. Growth has been relatively strong for

Computer-related services and Scientific and Technical services (i.e. biotech). Growing jobs in

these sectors is a provincial priority in an effort to support emerging high technology industries.

P a g e | 16

Employment in the Goods-producing sector, however, has weakened over time in the province,

particularly for the Primary industries and for Manufacturing. Employment in the Forestry

industry has continued to decline in the province driven by a number of factors – slowing

demand for primary outputs (lumber and pulp) as well as increased mechanization in

harvesting. Employment in Fishing in the province has also fallen over time, given supply

constraints for groundfish and weak markets for the key lobster industry. Mining has struggled

as well in the province with the closure of a large coal mine in Cape Breton and a variety of

smaller mines that produced Gypsum and other products (i.e. salt and zinc). On the brighter

side, the decline in the fisheries is being countered by a growing Aquaculture industry in the

province, and biomass energy is emerging as a market for forestry inputs. As well, there are

positive developments in offshore oil and gas that may help bring about recovery in the overall

Mining industry in the province.

Perhaps the most significant development in the Goods-producing sector in the province has

been the decline in Manufacturing in the region. While Manufacturing accounted for 11% of

employment two decades ago, currently it has fallen to below 7%. The decline has been

concentrated in manufacturing of primary goods. Manufacturing of Food and Beverage

products (particularly fish products) has declined significantly over time in the province, due to

supply constraints and international competition. Employment in Forestry products

manufacturing, particularly pulp and paper processing, has significantly been reduced over the

last decade, while many sawmills in the province have closed due to slowing demand for lumber

products. This past year also saw the end of oil and gas refining in the province, with the closure

of the Imperial Oil refinery.

Although Manufacturing remains challenged in the province, there are positive developments.

The Irving Shipyard contract should give a significant boost to the shipbuilding industry in the

province starting in 2016, and it is expected that this activity will spill over into other industrial

sectors in the province such as in metal fabrication. There are also a variety of smaller

manufacturers of innovative products emerging in the province (i.e. LED lighting systems) that

should help support Manufacturing employment over the forecast period.

Finally, a key Goods-producing sector that has also been challenged over the recent past and is

expected to continue in decline over the forecast period is Construction. Construction accounts

for over 7% of employment in the province and peaked in 2010. Since that period, a weakening

of major project activity in the province, a decline in housing starts, and sagging levels of

public/institutional investment have dampened prospects for the industry. In the longer term,

general economic improvement, increased commercial and higher density residential

development (particularly in the Halifax Area), and accommodating the longer term needs of an

aging population (senior friendly housing) should help strengthen the outlook for the industry.

P a g e | 17

Overview of Employment Outlook

The scenario used to produce the 2013-2015 sector outlooks for Nova Scotia was developed in

the third quarter of 2013. The discussion that follows focuses on those specific sectors where

significant trends and events of note are projected.

Figure 3

Distribution

of

Employment Growth

The Nova Scotia economy faces a number of

Nova

Scotia

2013-2015

competitive pressures and is expected to grow slowly

from 2013 to 2015. Employment in the province is

expected to be relatively stagnant over the forecast

period, growing by less than 1% comparing 2015

with 2013. This has roughly been a steady rate that

the province has experienced over the last three

years (2010-2012).

Other

Health

19%

Food/

Accom

35%

Nova Scotia continues to evolve as a service

10%

economy as opposed to a producer of goods.

Reflecting this, employment will increase primarily in

10%

service-related industries over the forecast period,

Fin, Ins,

16%

Real

10%

accounting for almost 80% of additional employment

Estate

in the province. The greatest increase in employment

Prof, Sci &

in the service sector will be in Health services, driven

Tech

Mining, Oil/Gas

primarily by the needs of an aging population. A

much smaller, but still significant, increase is

expected for employment in Professional, Scientific and Technical Services, reflecting

increasing prevalence of knowledge intensive firms in the province. A more positive outlook is

anticipated for Mining services, given a significant increase in offshore exploration activity and

the potential for other mining ventures in the province. Finance, Insurance and Real Estate and

Accommodation and Food Services are also expected to contribute to employment growth in

the province from 2013-2015.

The provincial economy is also expected to receive a significant boost from the shipbuilding

activity that will be undertaken in the Irving Shipyard in Halifax. However, production of the ships

is not expected to begin until late 2015 and is on the outer edge of this forecast. The industrial

employment outlook for shipbuilding will change significantly in our next forecast which will

encompass 2016, an anticipated year of full production at the shipyard.

There will be challenges for significant industries in the province over the forecast period.

Employment in Construction is expected to soften due to a slowdown in residential construction

and limited major project activity. Employment in Trade is also expected to weaken given high

levels of consumer debt, restrained economic activity, and restructuring within the retail trade

sector. Employment in Public Administration is anticipated to decline from 2013-2105, due to

continued government budgetary restraints.

P a g e | 18

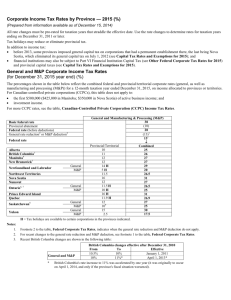

Table 3: Nova Scotia Industrial Outlook

2012

Total, All Industries

Share of

Employment

Annual

Average

Growth Rate

2010-2012

Annual

Average

Growth Rate

2013-2015

455500

100

0.3

0.3

85163

18.7

-0.9

0.1

Agriculture

5997

1.3

1.7

-0.8

Forestry, Fishing and Hunting

6997

1.5

-13.3

0.9

Mining and Oil and Gas

4398

1.0

27.6

4.4

Utilities

4198

0.9

0.0

0.9

Construction

31186

6.8

-1.4

-1.0

Manufacturing

32386

7.1

-0.5

0.4

370337

81.3

0.6

0.4

Trade

71569

15.7

-3.2

-0.2

Transportation and Warehousing

20191

4.4

4.5

0.0

Finance, Insurance and Real Estate and

Leasing

23890

5.2

-1.1

0.8

Professional, Scientific and Technical Services

25489

5.6

3.9

1.3

Management and Administrative Services

20291

4.5

-7.3

0.3

Educational Services

38683

8.5

7.5

-0.1

Health Care and Social Assistance

69370

15.2

0.5

1.0

Information, Cultural, Recreation

18592

4.1

-2.4

0.1

Food and Accommodation Services

31386

6.9

5.1

0.6

Other Services

21191

4.7

6.7

0.4

Public Administration

29687

6.5

-1.5

-0.3

Goods-producing

Services-producing

Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey; Employment and Social Development Canada, ROOCS

P a g e | 19

Industries Projected to Grow

The following industries are expected to show some substantial growth from 2013 to 2015. For

this analysis, substantial growth is defined as an increase of at least 150 in employment levels.

Overall, seven industries are expected to show significant growth in Nova Scotia over the next

three years.

Health Care

Figure 4 - Health Care Employment

Nova Scotia 2000-2015

000's

70.1 70.8 71.5

60

Outlook

13-15

40

+1400

(1%)

13

12

11

10

09

08

07

06

05

04

03

02

01

2000

Employment increases in Health Care are

20

expected to be fairly broad within the

industry, with increases expected for

hospitals, nursing & residential care

Historical

Projection

facilities, as well as increases in Social

Assistance (including community support services such as food banks and elderly support

services.) Growth in Health services will continue to be restrained, however, by budgetary

restraint given constricted government budgets and reduced public spending levels.

15

80

14

Health Care will provide the greatest

boost to employment growth in the

province over the forecast period. The

growth is driven by increasing demand for

Health Care services by an aging

demographic in the province.

Professional, Scientific and Technical Services

25.8 26.1 26.5

Outlook

13-15

15

+700

(1.3%)

Historical

Projection

Although growth in this industry grouping overall is not expected to be as robust as for the 20102012 period due to slow economic growth, the outlook is particularly positive for Computerrelated services. The Computer-related service component of this industry group is expected to

15

14

13

12

11

10

09

08

07

06

05

04

03

02

0

01

This sector is comprised of a wide range

of

knowledge

intensive

activities,

including Legal, Accounting, Architectural

and Engineering firms, Marketing and

Advertising,

and

Computer-related

services.

30

Figure 5 - Professional, Scientific & Technical

Services Employment

Nova

Scotia 2000-2015

000's

2000

Employment in Professional, Scientific

and Technical Services is expected to

add 700 jobs over the forecast period, the

second largest sectorial growth in the

province.

P a g e | 20

continue to strengthen over the forecast period, given the growing prevalence of technology.

Slower growth is expected to be evident for the Scientific Research services, given that much of

this activity is publically funded and subject to the current state of budgetary restraint.

Mining, Oil and Gas

15

14

13

12

11

10

09

08

07

06

05

04

03

02

01

2000

Employment in the Mining, Oil and Gas

Figure 6 - Mining, Oil & Gas Employment

Nova Scotia 2000-2015

industry in Nova Scotia is expected to

5

4.6 4.8

recover and to increase modestly over the

5 000's

forecast period. This sector, however, is

very small in terms of employment in the

Outlook

13-15

province. Employment growth in this

2.5

sector is expected to be supported by

+400

strength in offshore oil and gas production

(4.4%)

0

at the Sable and Deep Panuke fields. Oil

and gas development will get a significant

Historical

Projection

boost with Shell and British Petroleum Oil

committing over $2 billion dollars in

exploration activity in the region. There is also activity in other mining sectors in the province,

with the opening of the Dufferin and Touquoy gold mines. A recent survey of the Mining industry

in the province indicates that the outlook for Mining is positive with a rebound anticipated in key

sectors, such as Gypsum mining, as the US recovers and demand resumes for exports of

gypsum wallboard.

Finance, Insurance and Real Estate

000's

24.1 24.3 24.5

Outlook

13-15

+400

(0.8%)

15

12

11

10

09

08

07

06

05

04

03

02

01

2000

Employment is expected to slowly

15

strengthen in Finance, which include not

only the banking industry but also

investment and securities dealers and

0

credit financing firms. Continued strength

is expected as well in the Insurance

Historical

Projection

industry in the province, particularly in

Halifax which has traditionally been the regional centre for Atlantic Canada. On a more

restrained note, employment in Real Estate is not expected to grow significantly over the

forecast period, given an anticipated weakness in housing sales and starts in the province.

14

30

Figure 7 - Finance, Insurance and Real Estate

Employment

Nova Scotia 2000-2015

13

Employment in Finance, Insurance and

Real Estate is expected to grow slowly

over the forecast period, adding an

additional 400 jobs from 2013-2015.

P a g e | 21

Accommodation and Food Services

Figure 8 - Accommodation & Food Employment

Nova Scotia 2000-2015

Employment in Accommodation and Food

Services is expected to increase over the

forecast period; however, the growth rate is

expected to be significantly lower than for the

2010-2012 period. Weak levels of tourism,

heavy debt levels for domestic consumers,

and a slow economy have worked as serious

challenges to increasing employment in this

sector.

40

000's

31.6 31.8 32

20

Outlook

13-15

+400

2000

01

02

03

04

05

06

07

08

09

10

11

12

13

14

15

0

Historical

Projection

Employment in this sector is concentrated in

food and beverage services (80 percent), with a smaller share being employed in hotels and

inns. It is expected that the sector generally will improve over the forecast period, with an

anticipated increase in tourism with the resumption of a ferry service between Yarmouth and the

US. Although a weak economy has been a challenge to domestic demand for services in this

sector, a gradual recovery in the provincial economy should help maintain consumer spending

and support employment in food and beverage services. On the accommodation front, a

number of new hotels have emerged, particularly in the Halifax area. The completion of the

Halifax Convention Centre by early 2016 should also build momentum in the industry in the

Halifax Regional Municipality and for the province in general.

Manufacturing

Figure 9 - Manufacturing Employment

Nova Scotia 2000-2015

000's

50

32.5 32.7 32.8

25

Outlook

13-15

+300

(0.4%)

0

14

13

12

11

10

09

08

07

06

05

04

03

02

01

2000

It is anticipated that over the forecast

period, employment in the traditional

Historical

Projection

sectors will not decline further and should

strengthen. As evidence of this, Nova

Scotia merchandise exports strengthened in 2013, with paper, shellfish, and lumber contributing

significantly to the improvement. In addition, it is expected that the key sector of rubber

manufacturing will remain strong in the province, as evident by strong markets for tire products

in the U.S. A positive but restrained outlook is also expected for emerging manufactures of a

variety of products that incorporate newer technologies (i.e. electronic goods). Impetus for a

recovery in manufacturing is also expected with shipbuilding work being undertaken at the Irving

Shipyard, with activity really ramping up by the end of the forecast period.

15

Employment in Manufacturing is expected

to recover slowly over the forecast period.

Manufacturing in the province has been

challenged heavily by weaknesses in the

traditional

primary

based

Goodsproducing sectors over the last decade,

particularly those based on forestry and

fishing products.

P a g e | 22

Other Services

Figure 10 - Other Services Employment

Nova Scotia 2000-2015

30

000's

21.3 21.4 21.5

15

Historical

15

13

12

11

10

09

08

07

06

05

04

03

02

01

0

14

Outlook

13-15

+200

(0.4%)

2000

Employment in Other Services is

expected to expand modestly from 2013

to 2015. This industrial sector is

comprised of a wide variety of industrial

activities, including Automotive Repair

and Maintenance, Personal and Laundry

services, and Religious and Civic

Organizations. In the province, the two

largest service groupings by far in this

category are Repair Services and

Personal Services. In both these sectors,

there is a relatively high level of

representation of self-employment.

Projection

It is expected that employment in Other Services will continue to slowly expand as the economy

improves. In particular, the demand for Personal Care Services (hair care and esthetic services)

funeral services, and laundry services should remain strong and growth should continue. There

is also some expansion projected in Other Personal Services, particularly pet care services,

although many who work in these sectors may be self-employed.

Industries Projected to Decline

The following industries are expected to show important decline from 2013 to 2015. For this

analysis, important decline is defined as a decrease of at least 150 in employment levels.

Overall, only three industries are expected to show important decline in Nova Scotia over the

next three years.

Figure 11 - Construction Employment

Nova Scotia 2000-2015

Construction

40

000's

30.9 30.6 30.3

15

14

13

12

11

10

09

08

07

06

05

04

03

02

01

2000

Employment in the Construction industry is

expected to continue to decline in the

20

Outlook

province over the forecast period. The poor

13-15

-600

outlook for Construction activity reflects fairly

(-1.0%)

weak levels of major project activity currently

0

in the province. Some recovery is expected in

2014, however, with the construction of the

Historical

Projection

Maritime Link, ongoing construction at the

Halifax Shipyard, and the possibility of the Liquefied Natural Gas terminal in the eastern part of

the province. The outlook is less optimistic for residential construction, with relatively weak

P a g e | 23

levels of housing starts expected in the province, particularly in single family dwellings. On the

commercial front, it is expected that the recovery from the current slump in non-residential

construction investment will be challenging and will be further impacted by continued weakness

in institutional and governmental investment in the province. There have been some positive

developments such as the construction of the Nova Convention Centre and other significant

projects in the province (i.e. Forest Lakes Golf Community), but many of these projects are

longer term in nature and are projected to have limited impact over the forecast period.

Trade

Figure 12 - Trade Employment

Nova Scotia 2000-2015

Public Administration

15

14

13

12

11

10

09

08

07

06

05

04

03

02

Figure 13 - Public Administration Employment

Nova Scotia 2000-2015

50

000's

29.6 29.5 29.4

25

Historical

Projection

15

14

12

11

10

09

08

07

06

05

04

03

02

01

0

13

Outlook

13-15

-200

(-0.3%)

2000

Employment in Public Administration is

expected to continue to decline between

2013 and 2015. Employment in this industry

group is heavily comprised of Federal public

service employees, where roughly half the

public sector is employed in the province.

Employment declines are anticipated as

governments at all levels contend with

relatively large budget deficits and try to

improve their fiscal positions.

01

2000

Employment in Trade is expected to decline

90 000's

marginally over the forecast period.

71.4 71.3 71.1

Employment in this industrial category is

60

comprised primarily of Retail Trade, which

Outlook

13-15

makes up well over 80% of employment.

-300

Although there have been several high

(-0.2%)

30

profile entrants into the provincial retail trade

environment, such as Target, this has

Historical

Projection

generally come at the expense of existing

retail operators. With a fairly weak economy,

and generally high levels of consumer debt, it is not expected that retail trade employment will

regain the record high employment levels experienced between 2006 and 2009. A boost to retail

sales was expected with an announced cut in the HST by one percentage point, but this

decrease is now on hold until the fiscal position of the provincial government improves. A further

factor which will challenge retail sales employment is an apparent move toward online shopping

by consumers, with several large retailers, such as Best Buy, re-profiling their operations to

focus increasingly on online sales and away from retail storefront operations.

P a g e | 24

Industries with No Significant Change

The industries listed in this section are considered to show no significant change over the

forecast period (2012-2015). The threshold used to determine little or no significant change was

a change of 150 in employment levels or lower over the three year period.

The following sectors are not expected to demonstrate any significant change in employment

over the forecast period. They include:

Agriculture;

Forestry and Logging;

Fishing;

Utilities;

Transportation and Warehousing;

Management and Administration Services;

Educational Services; and

Information, Culture, and Recreation.

P a g e | 25

Conclusion

In conclusion, the provincial economy has been restrained over the most recent years, but it is

expected to begin to improve over the 2013-2015 period. The improvement is anticipated to rest

heavily on a recovery in spending on major projects in the province, particularly the shipbuilding

contract, where work is expected to commence in late 2015. Other significant projects, such as

the Maritime Link and various large commercial/industrial projects, should also lead to an

improved economy over the forecast period.

Reflecting the rebound in the provincial economy, the labour market is expected to grow slowly

from 2013-2015 and generate a moderate amount of employment growth. Many of these job

opportunities will be in the Health Care industry, which will account for much of the expansion in

employment in the province. Job growth will also be evident for the Professional, Scientific &

Technical sector in the province, as well as for the Mining, Oil and Gas industry and to a lesser

degree Finance, Insurance & Real Estate and Accommodation and Food Services. On a less

positive note, employment is expected to continue to weaken in the Construction sector in the

province and to slowly decline for Trade over the forecast period.

Note: In preparing this document, the authors have taken care to provide clients with labour market

information that is timely and accurate at the time of publication. Since labour market conditions are

dynamic, some of the information presented here may have changed since this document was

published. Users are encouraged to also refer to other sources for additional information on the local

economy and labour market. Information contained in this document does not necessarily reflect official

policies of Employment and Social Development Canada.

For further information, please contact Randy Jewers (randy.jewers@servicecanada.gc.ca) or the LMI

team at: lmi-imt@jobbank.gc.ca

For information on Statistics Canada products, please visit the Statistics Canada Web site at:

www.statcan.gc.ca

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada as represented by Employment and Social Development

Canada, 2014, all rights reserved

P a g e | 26

ANNEX 1

Three-year Employment Forecast

The three-year employment forecast has been designed to produce projections of employment

by industry and by occupation for a three-year period.

The model used to develop the employment projections has four components:

1) Analysis of the Macroeconomic Environment

1.1 A number of macro-economic indicators are developed by the Conference Board of

Canada and validated by the national and regional economists – GDP, Household

Income, Consumer Price Index, Labour Market Indicators, etc.

1.2 Forecasts for labour market indicators are developed, based on provincial

demographic projections and expected job growth. The labour market indicators include

the employment rate by age, the labour force participation rate, and the unemployment

rate.

2) Industrial Analysis

The industry employment estimates are generated by establishing an initial estimate of

employment by industry for the province. The model uses the COPS 33 industry forecast

and disaggregates into more detail for provinces where the data is large enough.

2.1 This first step creates an initial estimate of employment by industry over three years.

In order to do this, these tools are used:

i) Data from the Canadian Occupational Projection System (COPS)

ii) Information about the current and expected future economic environment, both

national and global, produced by organizations such as the Conference Board of

Canada, the Atlantic Provinces Economic Council, and by financial institutions.

3) Occupational Analysis

This step creates estimates of employment by occupation, using the list of 520 occupational

categories from the National Occupational Classification system (2006 version).

This step examines:

3.1 Expansion demand, i.e. growth/shrinkage in demand for workers due to

growth/shrinkage in the economy and industry.

Forecasts of employment by industry are converted into employment by occupation,

based on the estimated relative shares of each occupation in the overall employment of

an industry. The relative shares are estimated using Census numbers. Since these are

only updated every five years, current information from the Labour Force Survey are

also used, and econometric equations estimate the effect of changes in occupational

shares over time.

P a g e | 27

3.2 Replacement demand. This examines the demand for workers by occupation that

comes from the need to replace workers who exit the labour market for reasons such as

retirement and death.

3.3 Labour availability of experienced unemployed workers.

4) 4) Outlook Rankings

Each occupation is given a ranking as to whether demand for workers in that occupation

over the next three years is expected to be Good, Fair or Limited.

These overall rankings are determined by looking at four indicators:

i) Unemployment rate: Employment Insurance recipients / average employment in the

past three years

ii) Attrition rate: Total attrition during the forecasting period / average employment during

the forecasting period

iii) Employment Growth Rate: Average annual employment growth rate during the

forecasting period

iv) Net needs rate, which is Growth plus Attrition minus Unemployed Workers at the

beginning of the period

These quantitative results are reviewed and validated at the regional level using the

review of other indicators and consultations with other local stakeholders.

PRODUCTS:

The Labour Market and Strategic Analysis Directorate in the Atlantic provinces use the threeyear employment outlook projection system to develop the following products:

1) A three-year Sectoral Outlook report, by province

2) A three-year Occupational Outlook report, by province

3) Provincial Employment Potential Calls (EPCs) by occupation for the Job Bank website:

http://www.jobbank.gc.ca/

4) Provincial EPC trends by occupation for the Job Bank website:

http://www.jobbank.gc.ca/

P a g e | 28

References

1. APEC Major Projects Inventory (Spring 2013)

2. APEC Atlantic Report (Fall 2013)

3. The Conference Board of Canada - Provincial Outlook (Autumn 2013)

4. Bank of Canada - Monetary Policy Report (October 2013)

5. RBC Economics – Provincial Outlook (December 2013)

6. TD Economics – Provincial Economic Forecast (January 2014)

7. BMO Capital Markets – Provincial Update (December 2013)

8. Nova Scotia Department of Finance: Current Economic Environment - Dec 19, 2013

9. Nova Scotia Department of Finance: Daily Stats releases, received by email.

10. Globe and Mail: News articles and Report on Business

11. Chronicle Herald: News articles

12. Canada Broadcasting Corporation: Online News articles

13. Nova Scotia Tourism Agency: Nova Scotia Tourism Facts

14. CMHC: Housing Market Outlook, Halifax and Atlantic, Fall 2013

15. Service Canada: Sectoral Outlook 2013-2015, Quebec Region.

16. Buildforce Canada: Construction Looking Forward Report