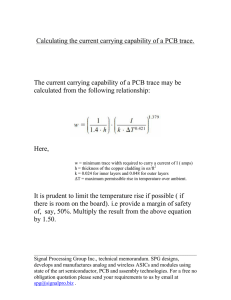

preliminary assessment of efforts made toward the

advertisement