National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA)

advertisement

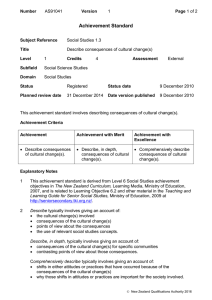

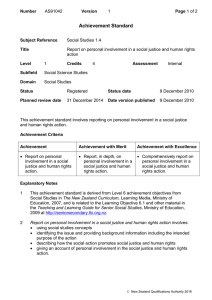

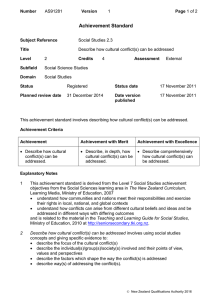

2005/07 November 2005 National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA) Executive Summary • The National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA) is a standards based qualification that has replaced School Certificate, Sixth Form Certificate and Bursary in New Zealand Schools. It is a series of qualifications registered on the National Qualifications Framework. • The NCEA qualification is awarded to students who achieve a specified number of credits at the required level. The level one qualification also involves a minimum literacy and numeracy standard. • Students are assessed against pre-assigned standards. These standards comprise elements of knowledge and skills, which students accumulate progressively until they have achieved enough at each subject and level to be awarded a national certificate. NCEA involves both internal as well as external assessment approaches. • NCEA differs considerably to the system it replaces: School Certificate, Sixth Form Certificate and Bursary, where a student’s performance was judged relative to other students through norm referencing. • 2004 was the first year that students sat level three NCEA, which is the highest level of the qualification. • Results from 2004 have prompted much discussion, especially around whether the observed variability in attainment that has occurred reflects variability in actual scholastic ability; is due to the removal of scaling or for other reasons. A review team has made recommendations to scale results where undue variability is apparent. Introduction This paper describes the National Certificate of Educational Achievement. It describes the basis of operation of the qualification within the National Qualifications Framework and the use of standards and credits; describes standards based assessment and discusses the difference between this and norm-referenced assessment; discusses the reasoning for the development of the qualification, providing a brief history of advocacy for change that eventually led to NCEA; and finally discusses some of the reactions to NCEA, the results for 2004 and future directions for NCEA, based on recommendations made in review. Approaches to assessment: standardsbased and normreferenced assessment NCEA is founded on a standards-based assessment of achievement in that students are assigned credits on the standards they actually achieve. It replaced School Certificate which principally used a norm-referenced assessment approach. There are several different types of assessment. In standards-based assessment a learner’s performance is measured against standards of achievement or competence. Results are reported in terms of what the learner has been assessed as being able to do. Norm-referenced assessment is where a learner’s achievement is ranked against the achievement of others in a group. A ranked list of learner outcomes are reported as percentage marks or grades. A student’s achievement is defined by their position on the rank in relation to other learners. What an individual knows or can do is not directly reported. 1 Norm-referenced approaches typically involve scaling. Scaling is used where the overall level of scores differs from year to year and subject to subject to give an appearance of consistency. This has in the past created the illusion of consistent standards, however what a student knows and can do is not reported and this approach is unable to detect overall improvement in group performance. NCEA does not as yet involve the use of ranking or scaling. National Qualifications Framework (NQF) When describing NCEA, it is first necessary to describe the framework that it operates within and the rules that it operates under. The National Qualifications Framework (NQF) is a hierarchical structure within which qualifications are registered. The framework is designed to provide nationally recognised, consistent standards and qualifications and recognition and credit for all learning of knowledge and skills. It is administered by the New Zealand Qualifications Authority (NZQA). Qualifications on the framework are gained through the accumulation of “standards”. Standards are the means to assess attainment of specified levels of knowledge and skills. NQF Levels There are ten levels in the qualifications framework. These levels reflect the level of complexity of a qualification - one is the least complex and ten, the most. They do not equate to 'years spent learning' but reflect the content of the qualification. NCEA standards, known as “achievement standards”, have been written at levels one to three. The new Scholarship qualification, which is not part of NCEA, operates at level four. 2 1 NZQA. 1991. Designing the Framework – a discussion document about restructuring national qualifications. NZQA, Wellington. 2 New Zealand Scholarship is a separate qualification. 2 Table 1: National Qualifications Framework Levels 1- 4 3 Process, Learning Demand and Responsibility Carry out processes that Level 1 • • • Level 2 • • • are limited in range are repetitive and familiar are employed within closely defined contexts are moderate in range are established and familiar offer a clear choice of routine responses Employing • • • • • • • Level 3 • • • Level 4 require a range of well developed skills offer a significant choice of procedures are employed within a range of familiar contexts • • • require a wide range of technical or scholastic skills offer a considerable choice of procedures are employed in a variety of familiar and unfamiliar contexts • • • • • • • • Applied recall a narrow range of knowledge and cognitive skills no generation of new ideas basic operational knowledge readily available information known solutions to familiar problems little generation of new ideas • • • some relevant theoretical knowledge interpretation of available information discretion and judgement a range of known responses to familiar problems • a broad knowledge base incorporating some theoretical concepts analytical interpretation of information informed judgement a range of sometimes innovative responses to concrete but often unfamiliar problems • • • • • • • • • • • in directed activity under close supervision with no responsibility for the work or learning of others in directed activity under general supervision and quality control with some responsibility for quantity and quality with possible responsibility for guiding others in directed activity with some autonomy under general supervision and quality checking with significant responsibility for the quantity and quality of output with possible responsibility for the output of others in self-directed activity under broad guidance and evaluation with complete responsibility for quantity and quality of output with possible responsibility for the quantity and quality of the output of others National Standards The standards are the nationally agreed and registered criteria by which student achievement is measured. National standards consist of collections of knowledge and skills grouped together and positioned at a level on the framework. They are considered by their creators to encompass the required quantum of knowledge and learning for their subject and level on the framework and a registration process evaluates whether this is so. They cannot be changed or modified unless by a formal review process. Unit and Achievement Standards Standards are the building blocks of qualifications on the Framework. Standards currently take two forms: unit and achievement standards. Each standard comprises components that, once achieved, earn credits that can be accumulated towards material qualifications. Unit standards generally are created to apply in industry training and other non-school settings, however both achievement and unit standards can be used to count towards NCEA. Unit standards are created by standards setting bodies and those involved in administering industry training, such as Industry Training Organisations (ITOs). For NCEA, national standards are known as achievement standards. Achievement standards are those based on the New Zealand Curriculum, prepared by the Ministry of Education in its role as a standards setting body. The achievement standards have been created under the management of the Ministry of Education specifically for the school system and NCEA. They are curriculum related; are placed at NQF levels one, two and three and cover fields of study previously covered by School Certificate, Sixth Form Certificate and University Bursaries. 4 3 Adapted from New Zealand Qualifications Authority website. For descriptors of all 10 levels, see http://www.nzqa.govt.nz/framework/levels.html 4 See NZQA, 2002. Unit standards and achievement standards - what's the difference?. In QA News, http://www.nzqa.govt.nz/publications/newsletters/qanews/june-2001/story1.html#usa 3 Unit standards have only two levels of attainment: “not achieved” and “achieved”. Achievement standards comprise four possible outcomes: “not achieved”, “achieved”, “achieved with merit”, “achieved with excellence”. Credits Credits are the currency of the National Qualifications Framework. Credits are numerical values that are awarded for successful completion of standards. They may also be awarded for successful completion of other qualifications. Credits for achievement standards are allocated on the basis of the estimated time needed for a typical learner to demonstrate that all specified outcomes have been met. Generally, they are supposed to reflect the quantum of knowledge and skills required by a given standard within its specified level. National Certificate As its acronym suggests, NCEA is a National Certificate, based on the system of credit accumulation from achievement standards as described above. It is based on the attainment of skills and knowledge as detailed in each of the standards. There are many National Certificates and National Diplomas registered on the NQF. Qualifications such as National Certificates, Diplomas and some degrees are awarded on the basis of credit and standard accumulation to a specified total. Most university degrees do not operate on the framework, however. The NCEA National Certificate is awarded at levels one and three. The majority of students take NCEA through the school system, but it is open to anyone assessed through an accredited provider. Level 1 Students normally begin NCEA level one in Year 11, the equivalent of fifth form year under the old system. The level one qualification began in 2002, with the last administration of School Certificate in 2001. Students qualify for NCEA level one if they complete eighty credits at level one, as long as eight of those credits show numeracy skills and eight other credits involve literacy skills. Literacy skills can be shown through achievement in English or in te reo Māori standards, or a combination of these. Certain standards satisfy the requirement for numeracy and literacy skills (see below). Literacy and Numeracy standard requirements When students have achieved eighty credits, they are awarded NCEA level one certificate, providing that eight of these credits show the student has met basic literacy requirements and eight other credits show the student has met basic numeracy requirements. Currently these requirements are for a minimum of eight literacy credits, at level one or above, from any combination of the following standards: • any English achievement or unit standards • any Te Reo Maori or Te Reo Rangitira achievement or unit standards • any of the following Communication Skills unit standards: 1277 Communicate information in a specified workplace 2989 Read and assess texts to gain knowledge 2977 Read texts for practical purposes 10792 Write formal personal correspondence. A minimum of eight numeracy credits, at level one or above is required from any combination of the following to show numeracy: • • • 5 any Mathematics achievement or unit standards any Pangarau achievement or unit standards any Statistics or Probability unit standards. 5 NZQA , 2001. NCEA Update - Issue 9. http://www.nzqa.govt.nz/ncea/publications/updates/update9.html#2 4 Level 2 NCEA level two requires a minimum of sixty credits at level two or above and twenty credits at any other level. Credits can be used for more than one qualification so some NCEA level one credits already achieved by students can count towards NCEA level two. Level two students do not need to achieve a specific number of credits in literacy or numeracy standards and they do not have to complete the level one or two qualification before starting on level two or three. Level 3 In 2004 NCEA level three and the New Zealand Scholarship qualification replaced University Bursaries. To be awarded NCEA level three, students are required to achieve eighty credits, of which sixty must be at level three or above and twenty at level two or above. Entry Fees Students sitting NCEA have to pay an annual fee. Students are required to pay $75 out of a total cost of $400 per annum for entry to all NQF standards and up to three Scholarship subjects. Foreign fee-paying students are required to pay the full amount, as they are not subsidised. Parents can apply for financial assistance through their school if they are below certain income thresholds, based on the Community Services Card income eligibility criteria. Internal and External Assessment NCEA uses both internal and external assessment. Standards can involve any form of assessment that is a valid measure of the stated outcomes. This includes written examinations, essays and tests, performance in front of an examiner, and other assessment methods, as well as internal assessment. Standards amenable to external assessment are so assessed, with the remainder being assessed internally. NCEA is assessed using a roughly fiftyfifty mixture of internal (course work) and external (largely examination) assessment. Internal assessment comprises all those assessments where the assessment judgement is made within a learning institution. It is generally considered that external assessment can be used to validly assess only some of the capabilities developed in school students. Internal assessment takes place within schools and students are assessed by their own teachers on course work submitted throughout the year. External assessment takes place within schools, but generally involves external supervision of externally set and marked papers. Moderation NCEA, in common with most qualifications, involves a process of moderation which is a form of quality assurance. Moderation is the process of ensuring that the standard is applied across locations and subjects consistently, and that it is a valid interpretation of the standard. To promote a national consistency of judgements against the achievement and unit standards, moderators check samples of students’ work marked in every subject in every school. Both internal and external assessments involve moderation and moderators. In external assessment, independent moderators review papers set by external examiners, and evaluate whether the papers and associated marking schedules are valid instruments for assessing the relative standard. Moderation for internal assessment occurs both internally and externally. Teachers send away assessment activity, marking schedules and samples of student’s work to NZQA moderators, who check that the teachers’ judgements are at the national standard, and then send a report back to the 6 Nixon, M. The High Trust Model that Nobody Trusts. New Zealand Education Review, Vol. 10 No.16, April 28 – May 4 2005. 5 principal. Moderators are contractors, not full-time employees, and must be qualified subject teachers, tutors or school advisors. 6 Rationale for change Qualification and assessment framework (NQF) Most commentators agree that by the 1980s, qualifications in New Zealand were fragmentary and lacked coherence. Those existing at the time had grown in an ad hoc fashion and were no longer appropriate for the needs of learners, employment and society. The need for a coherent and coordinated qualifications structure was increasingly evident. The National Qualifications Framework (NQF) was developed to enable a “seamless” education system, one that would permit an easy progression through the different types of learning and eradicate the dichotomy between the elite “academic” education and “training”, which was seen as second class. Education and training operated under separate systems, with different cultures, forms of provision, qualifications and providers. 7 Changes to assessment in schools NCEA was created to fit into the new standards based National Qualifications Framework. The intended benefits of moving school-based assessment to the new framework included improved coherence between curriculum and qualifications and rationalisation of qualifications and assessment practices for conventional school subjects. 8 International movements in the 1980s and 1990s were towards improved achievement, including demands for accountability and standards based assessment. School assessment had been undergoing change since the 1960s. There was a long-standing conviction among education professionals that the existing qualifications did not fit the curriculum and did not meet the needs of users or the full range of students. 9 NCEA was developed to be outcomes driven, motivated by the wider push for clarity around what students actually learn in school. 10 Increasingly there was a desire for assessment that would provide information about student achievement that would show exactly what learning had taken place, coupled with a belief that the ranking (norm-referenced) marks-based approach did not provide this information. 11 There was also a concern about the de-motivating effects of academic failure on students. The Committee of Inquiry into Curriculum, Assessment and Qualifications in Forms 5 to 7 expressed a belief that is was important that an assessment system should recognise the achievement of individual students without diminishing the feeling of self-worth of other students, therefore a system in which high marks or grades gained by one student mean that another student must necessarily receive lower marks, such as ranking and scaling entailed, should be avoided. 12 The Committee was concerned to encourage young people to want to continue learning and received a high 7 Barker, A. Standards-Based Assessment : The Vision And Broader Factors. In Peddie, R. & Tuck, B. 1995. Setting the Standards - Issues in Assessment for National Qualifications. Dunmore Press, Palmerston North. 8 Education Review Office, 2004. Progress of NCEA Levels 1 and 2, and Readiness of Schools to Implement Level 3. Wellington. 9 Strachan, J. 2002. Assessment in Change: Some Reflections on the Local and International Background to the National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA). In New Zealand Annual Review of Education. Victoria University of Wellington. No.11, 2001. 10 O’Neill, A., Clark, J. & Openshaw, R. Mapping the Field: An Introduction to Curriculum Politics in Aotearoa / New Zealand. In O’Neill, A., Clark, J. & Openshaw, R. 2004. Reshaping Culture, Knowledge and Learning – Policy and Content in The New Zealand Curriculum Framework. Dunmore Press, Palmerston North. 11 Department of Education, 1987. Learning an Achieving – second report of the Committee of Inquiry into Curriculum, Assessment and Qualifications in Forms 5 to 7. Wellington. 12 Ibid, pg 57. 6 number of submissions supporting the elimination of the concept of failure from assessment. It advised the Minister of Education in1986 to introduce a system of grades in which achievement of all students is recognised without reference to passing or failing. There was also an international move towards awarding exit certificates, and away from awarding intermediate certificates. Australia had removed its school certificate equivalent by the mid 1970s and had no Form 6 equivalent to Sixth Form Certificate. History and Development These pushes for change eventually led to the development of NCEA. The process of review and reform that led to the introduction of NCEA goes back at least to the early 1970s and has been described as a process of “advocacy” and “evolution”. 13 The following timeline gives a brief overview of the advocacy and evolution that led to the introduction of NCEA: 14 1934 School Certificate (SC) introduced. 1945 SC became the only Form 5 award, awarded overall for results in English and best three other subjects. The majority of University Entrance passes were internally assessed from the late 1940s. 1967 SC was awarded in single subjects only. Since 1967 there has been no such thing as a nationally recognised overall "pass" in SC. 1969 There were calls for SC to be abolished, largely because it imposed one course and one examination on all, regardless of ability and failed the “fit for purpose” test. Education in Charge, a publication of the PPTA, called for agreed criteria, clearly stated learning objectives and profile reporting instead of single figure results. 1972 There were discussions on the abolition (or at least partial internal assessment) of SC, and the need for specified learning outcomes. 1974 The report on the nation-wide Educational Development Conference proposed that SC be phased out and replaced by moderated teacher assessments, reporting on "levels of attainment" in each subject. In 1974 the fully internally assessed option for SC Art and Mathematics were introduced. Similar schemes were introduced in subsequent years for Science and English (1976) and Workshop Technology (1979). 1979 School Certificate Exam Board propose a fully internally assessed fifth form certificate. 1981 A New Zealand Employers Federation booklet called for full internal assessment of SC, assessment against standards, results as personal profiles and the removal of the distinction between so-called "academic" and "vocational" courses. The PPTA Journal contained a series of articles on assessment. Most writers promoted enhanced internal assessment and the recognition of a wider range of skills and abilities. 13 Strachan, ibid. This timeline is adapted from Lennox, B. Where did NCEA come from?. In New Zealand Qualifications Authority, 2001. QA News. Issue 38, June 2001. See: http://www.nzqa.govt.nz/publications/newsletters/qanews/june2001/featurewhere.html 14 7 1982 The Bursaries English examination marking schedule used written criteria for assessing literature essays. Over the next twenty years most marking schedules for School Certificate and Bursaries examinations introduced written criteria. In effect, student work was assessed against criteria (a form of standards) leading to the allocation of grades; then marks were allocated, generally without the use of criteria. 1983 Alison Gilmore from the New Zealand Council for Education Research (NZCER) discussed ways of moderating teacher assessments, including inspection, consensus and "group standards" as alternatives to statistical moderation. 1985 Warwick Elley (in the PPTA Journal) described our "sluggish advance towards internal assessment" and pointed out that few comparable countries have national examinations at all three levels. Elley promoted greater school flexibility in organising learning and saw the abolition of ranking and descriptions of what students "can do" as "a long-term ideal". 1985 The interim report of the Committee of Inquiry into Curriculum, Assessment and Qualifications in forms 5 to 7 led to the immediate abolition of the University Entrance examination and replaced with fully internally assessed Sixth Form Certificate (SFC), statistically moderated as proposed by Elley and Livingstone in 1972 (SFC had been in place alongside UE since 1969.) For the next eighteen years, until the introduction of NCEA level two examinations in 2003, New Zealand has two examinations for senior school students. 1986 Learning and Achieving (the full report of the 1985 Committee of Inquiry) called for far-sighted reforms. This was a key document in the evolution of assessment and qualifications in New Zealand. Overall, the report said, the move should be to enhanced school flexibility, enhanced internal assessment, and assessment against criteria. The report proposed: • • • for Form 5: full internal assessment using standards at three levels and leading to profile reporting. Schools should be able to design their own courses a similar system for Form 6 for Form 7: an achievement based system using five levels of achievement, partially internally assessed. The Department of Education commenced Form 6 achievement based assessment trials. Grade-related criteria were developed (at four or five levels) in the various aspects of each subject and trials held to investigate ways of moderating teacher assessments. This was an attempt to remove the predetermined national distribution of Sixth Form Certificate grades (where a pre-determined four percent of all candidates were awarded grade one) and statistical moderation of teacher judgements (using the previous year's SC results). In essence, the aim was to attach meaning to SFC grades. The trials ran until 1988 and were discontinued when more radical qualifications and assessment reform was signalled by the 1988 Hawke Report, in effect leading directly to the establishment of NZQA and the NQF. Many schools continued to use grade-related criteria in assessing for Sixth Form Certificate. This created confusion when schools had to reconcile their standards based results with the national norm-referenced structure. 8 1989 The Project ABLE report, the report of the Ministerial Working Party on Assessment for Better Learning, confirmed the directions of the Learning and Achieving report and added "SC has largely outlived its usefulness". The report called for a standards based approach and a single cumulative national certificate for school learners. 1990s There were three key developments in the nineties: • the national curriculum that was introduced for schools was based on written descriptions of learning outcomes for the separate aspects of each subject. It also validated school learning beyond traditional subjects • for the first time, all secondary qualifications were administered by one government agency, the New Zealand Qualifications Authority • The National Qualifications Framework had a demonstrable impact, especially in schools that were trying to introduce more varied and flexible learning in response to increased senior school retention rates. When government policy was being finalised, NCEA was described by some as a way out of the so-called "dual system": unit standards and the traditional examination based awards. At the time, schools could offer either or both as both were operating side-by-side. The government's intention throughout the nineties had been to remove the examination-based system once the Qualifications Framework was in place. (In 1993 the aim was to base all national schools qualifications on unit standards by 1997). 1997 The PPTA commissioned report on the Qualifications Framework, Te Tiro Hou reported wide support among its members for standards-based assessment over norm-based. It reported strong support for implementation of the Qualifications Framework at Years 12 and 13 and the retirement of Sixth Form Certificate once the Framework was in operation at Year 12, and retirement of School Certificate. 15 In 1997 the Government announced a policy called “Achievement 2001”, a complete overhaul of the secondary school qualifications system. 16 NCEA, a new group of qualifications, was to be based on both internal and external assessment through achievement standards. At least half of the credits for each subject were to be assessed externally, through written examinations and other assessments such as portfolios of student work. It was thought that the approach would reduce teacher workload and the risk of overassessment. Implementation NCEA was to be implemented from 2001 over a period of three years, to be fully implemented by 2003, in a staged process. In 2000, the new Labour Alliance Government decided to delay the start date from 2001 to 2002, judging that the system was not ready. Level one has been operational in schools since the beginning of 2002, level two from 2003 and level three was implemented from the beginning of 2004. 15 New Zealand Post Primary Teachers’ Association. 1997. Te Tiro Hou – Report of the Qualifications Framework Inquiry. Wellington. 16 Ministry of Education. 1999. Achievement 2001 – Qualifications for 16 to 19 year olds. Wellington. 9 Attitudes towards NCEA There are a wide variety of views about many facets of NCEA and standards based assessment. It seems impossible to be ambivalent towards NCEA, as is the case with many examinations and assessment systems worldwide: it is a subject that polarises educators and policy makers and there are strong opinions on either side. In New Zealand, there has been controversy over the best method of assessing performance of schoolchildren for decades, as the preceding timeline should illustrate. Many teachers, parents and employers favour the new system, some are not so sure. Discussions centre around the implementation, structure and administration of NCEA. A brief overview of some of the debate follows. Internal vs. External assessment Some commentators who take a contrary view to internal assessment see it as subjective, for example, they believe that under internal assessment, teachers are less likely to mark their own pupils “down” for a number of reasons: it may reflect badly on their own performance as a teacher; they may (consciously or not) wish the pupil to succeed so they may have a tendency to “mark them up”. Teacher judgements may also be influenced by the achievement of the rest of the group. They believe that external assessment is necessary to set a proper benchmark, a standard that all schools should achieve, and something tangible for students to work towards. 17 They believe that external examinations provide the means to assess students nationally to a minimum level of competence that is comparable across schools. External examinations can also promote common national teaching methods particular to subjects, for example, teaching languages in a certain way. Because the external examiners have never met the pupils they mark, there is less potential for bias or capture. On the other side of the argument, some think that external assessment encourages “teaching to the exam”, rather than to the curriculum: teachers may be tempted or forced to provide instruction narrowly to enable students to pass exams, rather than provide them with a wider range of learning and experience. There is some evidence that external examinations are not good predictors of success for pupils who proceed to university, and they are even worse predictors for those who go on to non-university study and employment. They believe that external assessment can’t assess many desirable capabilities and motivational and disciplinary effects apply more to some pupils than other. External assessments are one-off events, unlike real life, and are less of a level playing field than many believe. These factors have led most developed countries to place considerable emphasis on internal assessment in their exit certificate. 17 Elley, W.B. & Livingstone, I.D. 1972. External Examinations and Internal Assessments – Alternative Plans for Reform. New Zealand Council for Education Research, Wellington. 10 Standards based assessment Similarly, there has been much debate about the standards-based quality of NCEA. Some commentators prefer standards based systems because they see them as more valid, because they purport to report what a student can and cannot do. They believe that scaling and mark aggregation may reduce the value of ranking assessments as a source of information about student performance. Others prefer the ranking system of assessment because, for example, it enables employers to more easily categorise students and enables schools to provide aggregate measures of achievement of students. Schools that operate in competition with others to attract students (and therefore funding) rely on aggregate scores as they may be used as proxy measures of school quality. Moderation of internal assessments Similarly, there has been much debate about the moderation of internal assessments of NCEA, especially in light of the occurrences at Cambridge High School 18 where internally assessed standards were awarded to students who did not deserve them and the NZQA moderation system did not pick this up. 19 Some teachers are concerned that the external moderation of internal assessment system lacks credibility for several reasons. Some think there should be more moderation, that the current level is inadequate to make a full determination of quality and is not tough enough. They are also concerned about inconsistencies in moderator judgements and of “pettiness” by moderators and they believe that they should be able to enter into dialogue with moderators when communication between them is currently forbidden during moderation. There were also concerns about the lack of knowledge around the moderation appeals process and the disincentives for teachers to use it. The PPTA recommends that the moderation system be urgently reviewed (see section on Teachers below). On the other side, it is recognised that the current moderation system is a significant improvement over past practices and has considerable positive spin-offs. Parents and Employers Some parents and employers feel that NCEA results are difficult to understand 20 and some have expressed concerns in the system of moderation. 21 NZQA has responded to some parents’ and employers’ confusion over what results mean by arguing that NCEA provides more detail on what students can do than previous qualifications, and this opinion has been supported by other commentators 22. Students Researchers with the New Zealand Council of Educational Research (NZCER) have interviewed students regarding their experience of NCEA as part of the Learning Curves project. The preliminary results for the 2004 stage of the research indicates that students in all year levels thought that NCEA was a good qualification and that their credits, both external and internal, were valuable. 23 18 See: Education Review Office, 2004. Education Review Report – Cambridge High School – October 2004. http://www.ero.govt.nz/publish/reppub.ns4/Institution/5865640F66F19E3ECC256F26007A3684/$File/142.htm?OpenEl ement 19 Nixon, M. ibid. 20 Parents find NCEA results hard to decipher. The New Zealand Herald, 13th Jan 2005. 21 Thompson, A. Show us the evidence that these assessments are consistent. The New Zealand Herald, 18th Jan 2005. 22 Langley, J. Employers struggling to earn a pass. The New Zealand Herald, 18th Jan 2005 23 Gerritsen, J. The Kids are alright? New Zealand Education Review, April 7-13, 2005. 11 Teachers In a recent report, New Zealand teachers said that overall they support NCEA because they believed it was fairer to all students and they see NCEA as challenging and extending able students. 24 Those who gave unqualified support for NCEA listed their reasons as fairness, motivation of students, parity of esteem of different subjects and flexibility in developing courses to meet student needs as positive attributes. In only one group of participants was there complete consensus that the problems with the new system were so major that it would be better to return to the old system, and they qualified this by saying that the old system would still have to be modified. The participants identified a number of areas of concern that they recommended be subject to review including: • • • • • • • the integrity of external assessment. The comparability of difficulty level of external assessments between standards within a subject, between subjects and from year to year. Some teachers believe that within a subject the proportion of students achieving at different levels ought to be reasonably consistent between the various external assessments, in their view this is not happening. On the other hand, exams of the past exhibited such variations from question to question, so the difference may be that now these variations are able to be exposed the balance between curriculum delivery and assessment under NCEA, including whether assessment is driving curriculum delivery or whether curriculum delivery is driving assessment (as it should), and whether the integrity of the national curricula is being broken down under the new system. This criticism, it should be noted, was also applied to NCEA’s predecessors student behaviour demonstrates a greater concern with credit accumulation than with learning. Students in the middle range of ability are more likely to take a minimalist approach. Some students stop work once they have reached the number of credits necessary for the relevant certificate. Further some students who would otherwise achieve highly are content with an “achieved” because it qualifies them. Again, this criticism has been levelled at most assessment systems, including NCEA’s predecessors there is a loss of learning time under internal assessment: learning time is being taken up by assessment instead there is a feeling that students do not transfer knowledge and skills from one unit of work to another, due to the modularisation of assessment there needs to be more funding from Government to enable NCEA to operate as it is intended some teachers have complained of a higher workload under NCEA. New assessment systems always increase workload, however, which then drops back once familiarity grows 24 New Zealand Post Primary Teachers Association. 2005. Teachers Talk About NCEA – Research Report on Focus Groups with Secondary Teachers. NZPPTA, Wellington. 12 2004 Results NZQA announced in February that it would investigate the 2004 NCEA exam results at levels one and two where “significant variability” had been found, following issues with the variability of results for the new Scholarship exam. 25 NZQA has said that such an investigation is part of a standard practice to check a sample of results each year, as variability is expected. It regards the variability in the interim results for levels one and two NCEA 2004 as normal, and comparable to previous years. 26 Credit Achievement In 2004, seventy nine percent of students in their third year (Year 11), seventy six percent of students In their fourth year (Year 12) and seventy four percent students in their fifth year (Year 13) achieved at least forty credits. Fifty eight percent of the total Year 11 students, forty seven percent of Year 12 students and thirty nine percent of Year 13 students achieved at least eighty credits. Table 2: NCEA Trends over time Year of secondary education 2002 2003 2004 Total no. of NCEA qualifications achieved Year 3 Year 4 Year 5 28,626 1,851 687 30,473 27,590 3,997 33,827 37,090 28,910 Average no. of standards gaining credit per candidate Year 3 Year 4 27.0 10.0 28.1 22.7 28.5 24.0 Year 5 8.0 10.0 17.8 Year 3 Year 4 88.1 31.0 91.0 74.5 91.8 79.3 Year 5 26.7 33.6 68.6 Average no. of credits achieved per candidate Source: NZQA Secondary Qualifications Statistics 2004 http://www.nzqa.govt.nz/publications/docs/secondarystats-2004.pdf 25 Authority to look into fluctuations in other NCEA results. New Zealand Herald, 24th February 2005. New Zealand Qualifications Authority, 23 February 2005. NCEA Variability In Line With Expectations. Media Release. 26 13 Future directions The State Services Commission’s report, Report on the Performance of the New Zealand Qualifications Authority in the Delivery of Secondary School Qualifications was released in July 2005 in response to a request by the Associate Minister of Education to assess whether the apparent variation in NCEA results both between subjects and between years (where valid comparisons are possible) reflects deficiencies in NZQA systems. The review team found that, notwithstanding implementation difficulties, NCEA enhances learning outcomes for students and is improving teaching practice. Overall, it is acknowledged that the implementation of NCEA has been a massive undertaking and NZQA deserves credit for what has been achieved to date, as does the teaching profession. However, NZQA’s focus on the implementation of NCEA was not sufficiently strategic and the implementation path was too steep. The review team makes a number of recommendations to NZQA regarding the administration of NCEA, including that : • • • Further Information/ links NZQA should implement a scaling system for results that are outside the bands of accepted tolerance, unless there is a defendable explanation for that variation NZQA should look at ways it can improve the validity of moderation by randomly sampling student work and opening all standards to selection for moderation schools should report to NZQA when students fail to achieve standards (they were previously not required to) and NZQA should develop a nationally consistent approach to reporting nonachievement. New Zealand Qualifications Authority (NZQA) NCEA updates http://www.nzqa.govt.nz/ncea/publications/updates/index.html State Services Commission - Report of the performance of the New Zealand Qualifications Authority in the delivery of secondary school qualifications http://www.ssc.govt.nz/display/document.asp?docid=4703 Paul Mahoney, Research Analyst Social Policy Team Parliamentary Library For more information contact Paul (ext.9019) Copyright © NZ Parliamentary Library Except for educational purposes permitted under the Copyright Act 1994, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including information storage and retrieval systems, other than by Members of Parliament in the course of their official duties, without the consent of the Parliamentary Librarian, Parliament Buildings, Wellington, New Zealand 14