Creating A Digital New Zealand

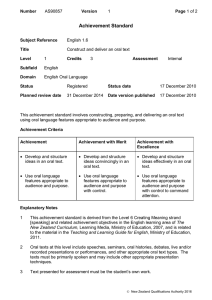

advertisement