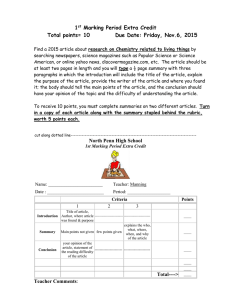

Appendix

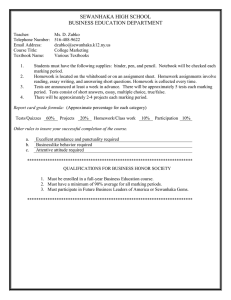

advertisement