View/Open - Victoria University

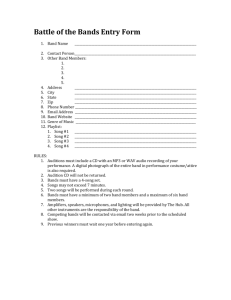

advertisement