1 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BEFORE THE FEDERAL

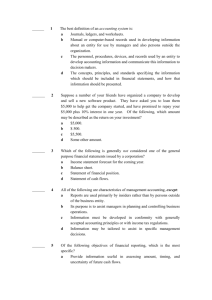

advertisement