Cultural Education Partnerships (England) Pilot Study

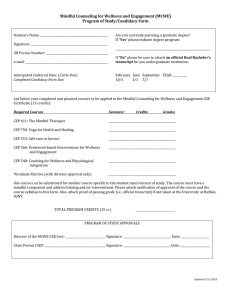

advertisement