How to Ensure Nutrition Security in the Global

advertisement

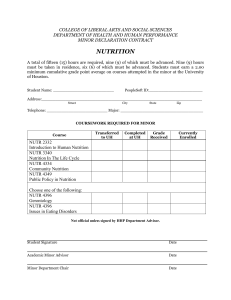

The Journal of Nutrition Supplement: The Impact of Climate Change, the Economic Crisis, and the Increase in Food Prices on Malnutrition How to Ensure Nutrition Security in the Global Economic Crisis to Protect and Enhance Development of Young Children and Our Common Future1,2 Saskia de Pee,3,4* Henk-Jan Brinkman,5 Patrick Webb,4 Steve Godfrey,6,7 Ian Darnton-Hill,4 Harold Alderman,8 Richard D. Semba,9 Ellen Piwoz,10 and Martin W. Bloem3,4,11 3 World Food Programme, Rome 00148, Italy; 4Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University, Boston, MA 02155; World Food Programme, New York, NY 10017; 6Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition, Geneva 1202, Switzerland; 7The School of Business at University of Cape Breton, Sydney, Nova Scotia, B1P 6L2, Canada; 8The World Bank, Washington, DC 20433; 9 Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21205; 10Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Seattle, WA 98102; and 11Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21205 5 The global economic crisis, commodity price hikes, and climate change have worsened the position of the poorest and most vulnerable people. These crises are compromising the diet and health of up to 80% of the population in most developing countries and threaten the development of almost an entire generation of children (~250 million), because the period from conception until 24 mo of age irreversibly shapes people’s health and intellectual ability. High food prices reduce diversity and nutritional quality of the diet and for many also reduce food quantity. Poor households are hit hardest, because they already spend 50–80% of expenditures on food, little on medicines, education, transport, or cooking fuel, and cannot afford to pay more. Reduced public spending, declining incomes, increased food and fuel prices, and reduced remittance thus impede and reverse progress made toward Millenium Development Goals 1, 4, and 5. Investments in nutrition are among the most costeffective development interventions because of very high benefit:cost ratios, for individuals and for sustainable growth of countries, because they protect health, prevent disability, boost economic productivity, and save lives. To bridge the gap between nutrient requirements, particularly for groups with high needs, and the realistic dietary intake under the prevailing circumstances, the use of complementary food supplements to increase a meal’s nutrient content is recommended. This can be in the form of, e.g., micronutrient powder or low-dose lipid-based nutrient supplements, which can be provided for free, in return for vouchers, at subsidized, or at commercial prices. J. Nutr. 140: 138S–142S, 2010. Introduction At least 3.5 million preventable under-5 deaths per year are due to undernutrition, which includes suboptimum breast-feeding, Published in a supplement to The Journal of Nutrition. Presented at the workshop “The Impact of Climate Change, the Economic Crisis, and the Increase in Food Prices on Malnutrition,” held in Castel Gandolfo, Italy, January 25, 2009. The workshop was organized by Martin W. Bloem, United Nations World Food Programme, Rome, Italy; Klaus Kraemer, Sight and Life, Basel, Switzerland; and Richard D. Semba, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and with the support of an educational grant from Sight and Life, Basel, Switzerland. Supplement contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the organization that they are affiliated with. Publication costs for this supplement were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This publication must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact. Supplement Coordinator disclosures: Martin Bloem, Klaus Kraemer, and Richard Semba have no relationships to disclose. Supplement Guest Editor disclosures: A. Catharine Ross and Richard Semba have no relationships to disclose. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and are not attributable to the sponsors or the publisher, Editor, or Editorial Board of The Journal of Nutrition. 1 138S especially nonexclusive breast-feeding in the first 6 mo of life, intrauterine growth retardation (low birth weight), stunting, severe wasting, and deficiencies of micronutrients such as vitamin A and zinc (1). Almost all of these are directly linked to the quality of dietary intake of children and mothers. According to the WHO, undernutrition accounts for 11% of the total global burden of disease. At least 178 million children worldwide are affected by chronic undernutrition or stunting (short stature) resulting from poor fetal growth and reduced growth in the first 2 y of life. This is due to inadequate nutrient intake, often exacerbated by infection, and amounts to a “life sentence” because of irreversible damage manifested in later life (2). The damage associated 2 Author disclosures: S. de Pee, H-J. Brinkman, P. Webb, S. Godfrey, I. Darnton-Hill, H. Alderman, R. D. Semba, E. Piwoz, and M. W. Bloem, no conflicts of interest. * To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: saskia.depee@wfp. org or depee.saskia@gmail.com. 0022-3166/08 $8.00 ã 2010 American Society for Nutrition. First published online November 25, 2009; doi:10.3945/jn.109.112151. Downloaded from jn.nutrition.org by guest on April 11, 2012 Abstract Deteriorating nutrition as a consequence of the global economic crisis The current global economic crisis represents the sharpest economic downturn since the Second World War. Developing countries face particularly difficult circumstances, reduced foreign capital flows, declining export revenues, falling devel12 Estimated as follows: 555 million under-5 children in developing countries (1) 3 (9+24=33 mo)/(0–59 mo) = 0.56 3 80% at-risk (see section, managing high food prices: the household response) = 250 million. 13 Abbreviations used: CFA, Comprehensive Framework for Action; MDG, Millennium Development Goal; WFP, World Food Program. opment assistance, and sharp increases in unemployment (both local and international, leading to reduced remittances from migrants), which could amount to 50 million job losses worldwide (6). As a result, incomes are declining and government budgets are under pressure, which could result in lower expenditures on social protection and public services. Malnutrition is expected to rise through lower incomes, the twin effects of lower subsidies or higher taxes on food and fuel, and reduced spending in the health, water, and sanitation sectors (7). The FAO food and cereal price indices declined by approximately one-third between June and December 2008 from the prior peaks. Slower growth, alleviation of weather-related supply constraints, easing of export restrictions, lower transport costs, and a stronger dollar have contributed to lower food prices. However, food prices are expected to remain relatively high because of structural factors, such as low stocks, low productivity growth, climate change, and demand for biofuels. In May 2009, the FAO cereal price index was still 1.8 times the 2005 level and 2.2 times the 2000 level (8). Changes in global prices do not always translate to a similar change in prices at the national level. At the local level, FAO estimates that in 80% of the countries with data, food prices are still higher than 12 mo ago (9). The impact on millions of household budgets has been dramatic. WFP regularly calculates changes in the costs of typical household food baskets in 35 countries, based on a weighted mean of price changes (10). Overall, the cost of the food basket, using prices for the latest available quarter in 2008, was 36% higher than for the same quarter in 2007 and 48% more expensive compared with the previous 5 y (11). This scenario of reduced public spending, declining incomes, loss of jobs, high food prices, higher costs for milling and cooking due to high fuel prices, reduced remittance income, and consequences of climate change (12) is a toxic combination that threatens the development of almost an entire generation of children in developing countries. Managing high food prices: the household response The groups most vulnerable to a deterioration of their nutritional status are those who spend a large proportion of their income on food (50–80% among the poor), buy more food than they sell, have few coping strategies at their disposal, and may face a further reduction or loss of cash income. This includes the urban poor, rural landless, pastoralists, and many small-scale farmers (typically ,20% produce enough surplus to be categorized as net-sellers) (11,13). These groups were already more vulnerable because of a less diverse diet and greater risk of infections and poor health. But in many countries, even the middle class, those living on US$6–10 per capita per day, are at risk, because food still accounts for 35–65% of their expenditures. In many developing countries, 80% of the population lives on ,US$10 per capita per day (14). Thus, high food prices and the global economic crisis affect the majority of the population in developing countries. Available evidence from the Asian economic crisis in the late 1990s as well as from Africa consistently shows that as prices increase, households first reduce consumption of more expensive food items, typically animal source foods (meat, poultry, eggs, fish, and milk), and fruit and vegetables that are good sources of high-quality nutrients. This is followed by a reduction of the size and frequency of meals (15–19). WFP household-level food security assessments conducted in 2008 found similar evidence as well as reductions in health care visits or health expenditures, increased school drop-outs, and sale of assets (20). Nutrition security in global economic crisis 139S Downloaded from jn.nutrition.org by guest on April 11, 2012 with undernutrition accumulated during the first 2 y of life can include increased susceptibility to infections; slowed cognitive development and growth; reduced school performance, including later enrolment and earlier drop-out; increased susceptibility to developing chronic diseases (diabetes, hypertension, and coronary heart disease) among children who gain weight rapidly in later childhood/adolescence; affected girls being at higher risk themselves later in life of having low birth weight babies, perpetuating the problem into another generation; and reduced productivity and lifelong earning potential (3). Thus, investment in early childhood nutrition protects health, prevents disability, boosts economic productivity, and saves lives. The long-term health and vitality of entire nations depends on the wellbeing of its individual children. Today, ~250 million infants and unborn children (29 to 24 mo of age) in developing countries are at risk12 and an already unacceptably high level of unnecessary, preventable child mortality and ill-health caused by undernutrition is getting worse. The importance of ensuring adequate nutrition, and especially combating micronutrient deficiencies, which has very high benefit:cost ratios, was also emphasized by the Copenhagen Consensus (4). The expert committee, which consisted of 8 economists, 5 of whom were Nobel laureates, declared in May 2008 that the world’s best investment from among 30 investments in any field is to provide vitamins and minerals for undernourished children. Providing micronutrients for 80% of the 140 million children who lack essential vitamins in the form of vitamin A capsules plus a course of zinc supplements would cost just $60 million/y while generating annual benefits worth more than $1 billion. The third top priority of the economic experts was micronutrient fortification involving the iodization of salt and fortification of basic food items with iron. Each dollar spent on this would result in benefits of more than $9. A report by the World Food Program (WFP)13 and the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean highlights the high economic costs of inaction (5). Two methods were used to estimate the economic impact of child undernutrition in Central America and the Dominican Republic. The first, which was called the “incidental retrospective dimension,” is a sum of the losses in a single given year due to child undernutrition. The measure sums the health care costs for the current under-5 cohort, the cost of repeated grades in schoolaged children previously impacted by undernutrition, and adult productivity losses in the given year due to the impact of their early childhood undernutrition on cognitive development or premature death. In 2004 alone, this dimension cost 7 countries nearly $7 billion. The second measure, the “prospective dimension,” projects future losses in health and education costs as well as productivity for the cohort of children who are under-5 in a given year. The 2004 under-5 cohort would accumulate nearly $2.3 billion in costs due to malnutrition over 65 y. Comprehensive response for the medium and long term Because of the severe and long-lasting effects of the current crises on nutrition and health, measures to mitigate this impact are urgently required. Such measures should focus on nutrition, especially during the window of opportunity from conception to 24 mo of age, and be immediately applied in the short term and sustained over the medium and long term. The Comprehensive Framework for Action (CFA) developed by the UN Secretary General’s High Level Task Force on the Global Food Security Crisis noted the urgent need to improve food and nutrition security worldwide, systematically and sustainably (32). Many necessary actions were identified, such as the need to scale up productivity-enhancing safety nets and promote agricultural investments focused on smallholder farmers and rural development. It was also stated that increased productivity must be accompanied by investment in local and regional market development and adjustments of distorting trade practices and that comprehensive, targeted social protection systems that achieve universal coverage of vulnerable groups and link to other basic social services will build resilience to future shocks. However, the CFA did not discuss details of 140S Supplement how to improve nutrition security. Based on the analyses in this document, such recommendations are provided below for inclusion in the CFA. The CFA also noted that the financial implications related to this crisis will be considerable, will exceed the response thus far, and will require substantial political and financial commitments from national governments first and foremost but also from the private sector, civil society, and the international system. For example, the World Bank just finalized an analysis of the financing needs for scaling-up nutrition programming, which estimates an annual requirement of US$10.3 billion (and an additional US$1.5 billion from households) (33). The estimate of the CFA for immediate food assistance, agricultural inputs, and budgetary and balance of payment support is US$8–13 billion per annum and an additional US$17–27 billion per annum for building longer-term resilience and contributing to food and nutritional security. The World Bank estimate includes less food and no agricultural inputs. Therefore, the extent of overlap and complementarity of the 2 estimates needs to be examined. Commercially available products of good nutritional value are potentially important tools for increasing dietary quality of specific groups (in addition to other measures such as exclusive breast-feeding for the first 6 mo of life and continued breastfeeding thereafter, good environmental hygiene, etc.) but are generally not affordable for people in need. In that case, access to such products can be provided in different ways, such as forfree distribution to specific vulnerable groups, either directly or through distribution of vouchers, and by making them available for sale using a variety of market channels. The advantage of a voucher system is that it can harness normal market mechanisms with sales at subsidized/low-profit/ commercial price to lower middle-class consumers, in which case social marketing and information about the product could be tailored to a larger target group, including buyers as well as those exchanging vouchers. Eligibility for vouchers can be linked to participation in other programs for the most vulnerable such as receipt of food assistance (food-for-asset, supplementary feeding, school feeding, etc.) or cash transfer programs. The latter could be conditional upon the use of specific services such as preventive health care or education, such as implemented in Latin America (34), or based on vulnerability criteria such as age (child-care grants or old-age pension) as, e.g., implemented in certain countries in Africa and Asia (35). For a detailed review of global experience on what does and does not work in safety nets, see Grosh et al. (36). Cash transfer programs are consistently found to augment household food consumption expenditures and dietary diversity (35). However, impact on micronutrient status appears limited, because households also spend some of the extra money they have available on health care, education, and other valuable investments (37,38), because micronutrient-rich foods or supplements are often expensive, availability may be limited, and awareness of their health value not very high. Providing a voucher would increase the likelihood that the commodity is obtained by the target group and its value would be demonstrated by its availability in the consumer market. Where markets are not functioning very well, or where implementing a voucher system is not feasible, the special nutritious commodities can be directly distributed to beneficiaries. However, this will require greater awareness raising about the benefits of consuming the commodity, the risk of leakage of the commodities may be greater, and when smaller quantities are required, this could also be less interesting for the private sector to produce. Downloaded from jn.nutrition.org by guest on April 11, 2012 This reduction of the consumption of nutrient-rich foods quickly increases the prevalence and severity of micronutrient deficiencies as well as stunting, particularly among population groups with high needs such as young children, pregnant and lactating women, and the chronically ill (16,21–23). The resulting increased susceptibility to infection further aggravates the situation because of increased nutrient losses and reduced appetite. In addition to micronutrient deficiencies, people who also have to reduce the size or number of meals will likely also suffer deficiencies in macronutrients and energy, which leads to thinness among adolescents and adults and weight loss and increased risk of acute malnutrition (wasting) among young children (24–28). The current crisis is therefore undermining progress made toward the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 1 targets of 50% reduction of underweight and hunger between 1990 and 2015 and the MDG 4 target of reduction in under-5 child mortality by two-thirds and making these and other MDG targets (such as MDG 5 on maternal mortality) even more difficult to achieve, especially in the poorest countries. The impact of high food prices and global economic crisis further compounded by climate shocks, even when of relatively short duration, have long-term consequences, because undernutrition endured between conception and 24 mo of age, has lifelong consequences for the individual as well as, in the case of girls, their offspring (2). Shocks to households’ current earnings and purchasing power reduce their future livelihood capabilities by degrading or destroying assets, resulting in reduced investment by the household in child nutrition, health, and education (29). These consequences that erode human well-being and longterm capabilities through nutritional pathways also seed potential future crises, whether of an economic, political, or environmental nature (30). Furthermore, the current crises underscore the fact that large segments of the world’s population face chronic food insecurity, leaving them disproportionately more exposed to shocks. Therefore, while addressing the nutritional needs of vulnerable populations in response to the present crisis is urgent, these populations should also be targeted with known nutritional interventions at all other times to ameliorate the persistent conditions that lead to increased mortality and morbidity (31). The strategy should also support public-private partnerships that link the private sector, governments, UN agencies, researchers, and not-for-profit organizations in the development and distribution of new, affordable, and nutritious food products. The recent Amsterdam Initiative on Malnutrition14 is an example of a replicable and innovative approach that will deploy new financial and program instruments to strengthen the role of business in helping the public sector tackle the nutrition crisis. Conclusion There is overwhelming evidence of the negative impacts of the current global economic crisis on nutrition and health, which has immediate consequences as well as long-term effects on individuals and societies, especially among children who are now between conception and 24 mo of age. Tackling this requires a variety of measures to increase dietary quality such that the intake of nutrients essential for health, growth, and development meets the needs of different target groups. Where animal-source foods, fruit, and vegetables in adequate amounts are beyond reach or cannot realistically meet the need for certain nutrients (such as iron for children aged 6–23 mo), home fortification using complementary food supplements (e.g. with 1 g/d micronutrient powder or 20 g/d lipid-based nutrient supplements) or fortification of specific foods can be used (39). Such commodities can be made available for purchase, in return for vouchers, or through blanket for-free distribution. Recommendations Figure 1 lists measures that are urgently required for mitigating the impact of the crises in such a way that nutritional quality of the diet of vulnerable populations is improved. These measures, which are for the short to medium term and go beyond food security, can be linked to the CFA developed by the UN Secretary General’s High Level Task Force on the Global Food Security Crisis (32). Furthermore, effective surveillance systems to monitor changes in the vulnerability and food and nutrition security of populations as well as the coping strategies employed in times of crisis need to be strengthened and expanded. Acknowledgments M.W.B. and S.d.P. conceptualized and designed the position paper; S.d.P and S.G. wrote the paper; H-J.B., P.W., I.D-H., H.A., R.D.S., E.P., and M.W.B. thoroughly reviewed and made suggestions for revisions of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Other articles in this supplement include (40–44). Literature Cited 14 The Amsterdam Initiative on Malnutrition is a public private programme supported by the Government of Netherlands, Dutch companies and academic institutions, and the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition. Launched on May 27 2009, it aims to address the nutrition needs of 100 million people in 6 African countries by 2015. 1. 2. Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, Caulfield LE, de Onis M, Ezzati M, Mathers C, Rivera J. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet. 2008;371:243–60. Victora CG, Adair L, Fall C, Hallal P, Martorell R, Richter L, Sachdev HS, for the Maternal and Child Undernutrition Study Group. Maternal Nutrition security in global economic crisis 141S Downloaded from jn.nutrition.org by guest on April 11, 2012 FIGURE 1 Proposed measures to mitigate the negative impact of the global economic and financial crises on nutrition, health, and development. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 142S Supplement 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 36. 37. 38. 39. 40. 41. 42. 43. 44. stunting among children 0–59 months old in Indonesia: implications of rising food prices. J Nutr. 2010;140:195–200. de Pee S, Bloem MW, Sari M, Soekarjo DD, Tjiong R, Kosen S, Muhilal, Satoto. Indonesia’s crisis causes considerable weight loss among mothers and adolescents. Malaysian Journal of Nutrition. 2000;6: 203–14. Martin-Prével Y, Delpeuch F, Traissac P, Massamba JP, Adoua-Oyila G, Coudert K, Trèche S. Deterioration in the nutritional status of young children and their mothers in Brazzaville, Congo, following the 1994devaluation of the CFA franc. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78: 108–18. Torlesse H, Kiess L, Bloem MW. Association of household rice expenditure with child nutritional status indicates a role for macroeconomic food policy in combating malnutrition. J Nutr. 2003;133: 1320–5. Campbell AA, de Pee S, Sun K, Kraemer K, Thorne-Lyman A, MoenchPfanner R, Sari M, Akhter N, Bloem MW, Semba RD. Household rice expenditure and maternal and child nutritional status in Bangladesh. J Nutr. 2010;140:189–94. Sulaiman M, Parveen M, Das NC. Impact of the food price hike on nutritional status of women and children. Research Monograph Series No. 38, January. Dhaka (Bangladesh): BRAC, Research and Evaluation Division; 2009. Alderman H. Safety nets can help address the risks to nutrition from increasing climate variability. J Nutr. 2010;140:148–52. Webb P. Medium- to long-run implications of high food prices for global nutrition. J Nutr. 2010;140:143–7. Christian P. Impact of the economic crisis and increase in food prices on child mortality: exploring nutritional pathways. J Nutr. 2010;140: 177–81. High-level task force on the global food security crisis. Comprehensive framework for action. July 2008. Available from: http://www.un.org/ issues/food/taskforce/Documentation/CFA%20Web.pdf. Horton S, Shekar M, McDonald C, Mahal A. Scaling up nutrition: what will it cost? Washington, DC: World Bank. In press 2009. Valpiani N, Thorne-Lyman AL, de Pee S, Godfrey S, Gentilini U, Bloem MW. Proposed strategies for mitigating the impact of high food prices on nutrition and health in Latin America and the Caribbean. CAB Rev Persp Agric Vet Sci Nutr Nat Res. 2008;81:. Yablonski J, O’Donnell M. Lasting benefits. The role of cash transfers in tackling child mortality. Save the Children UK. 2009 [cited 2009 Aug 14]. Available from: http://www.savethechildren.org.uk/en/54_8358.htm. Grosh M, del Ninno C, Tesliuc E, Ouerghi A. For promotion and protection. The design and implementation of effective safety nets. Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2008. Moench-Pfanner R, de Pee S, Bloem MW, Foote D, Kosen S, Webb P. Food-for-work programs in Indonesia had a limited effect on anemia. J Nutr. 2005;135:1423–9. Fiszbein A, Schady N. Conditional cash transfers reducing present and future poverty. Washington, DC: The World Bank. 2009 [cited 2009 Jun 23]. Available from: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTCCT/ Resources/5757608–1234228266004/PRR-CCT_web_noembargo.pdf. de Pee S, Bloem MW. Current and potential role of specially formulated foods and food supplements for preventing malnutrition among 6–23 months old and treating moderate malnutrition among 6–59 months old children. Food Nutr Bull. 2009;30:S434–63. Badham J. World food crisis: a wake-up call to save a generation of children participants statement: Castel Gondolfo, Italy, 25 January, 2009. J Nutr. 2010;140:130–1. Bloem MW, Semba RD, Kraemer K. Castel Gandolfo Workshop: An introduction to the impact of climate change, the economic crisis, and the increase in the food prices on malnutrition. J Nutr. 2010;140: 132–5. Nabarro D. Editorial comment: helping the vulnerable. J Nutr. 2010;140:136–7. West KP, Mehra S. Vitamin A intake and status in populations facing economic stress. J Nutr. 2010;140:201–7. Semba RD, de Pee S, Sun K, Bloem MW, Raju VK. The role of expanded coverage of the national vitamin a program in preventing morbidity and mortality among preschool children in India. J Nutr. 2010;140: 208–12. Downloaded from jn.nutrition.org by guest on April 11, 2012 12. and child undernutrition: consequences for adult health and human capital. Lancet. 2008;371:340–57. Hoddinott J, Behrman JR, Maluccio JA, Flores R, Martorell R. Effect of a nutrition intervention during early childhood on economic productivity in Guatemalan adults. Lancet. 2008;371:411–6. Copenhagen Consensus [cited 2009 Sep 8]. Available from: http://www. copenhagenconsensus.com/CCC%20Home%20Page.aspx. Martı́nez R, Fernández A. The cost of hunger: social and economic impact of child undernutrition in Central America and the Dominican Republic. Project document. Santiago, Chile: United Nations, Economic and Social Commission for Latin America; 2008 [cited 2009 Aug 14]. Available from: http://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/liaison_offices/ wfp127796.pdf. International Labour Organization. Global employment trends. Geneva: International Labour Organization; 2009. Timmer CP. Preventing food crises using a food policy approach. J Nutr. 2010;140:224–8. World Food Situation FAO. Food price indices [cited 2009 Jun 19]. Available from: http://www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/FoodPricesIndex/ en/. FAO. Global information and early warning service. Crop prospects and food situation. Rome: FAO; April 2009. World Food Program. Recent food price developments in most vulnerable countries. Issue No. 2. Rome: World Food Program; 2008. Brinkman H-J, de Pee S, Sanogo I, Subran L, Bloem MW. High food prices and the global financial crisis have reduced access to nutritious food and worsened nutritional status and health. J Nutr. 2010;140: 153–61. Darnton-Hill I, Cogill B. Maternal and young child nutrition adversely affected by external shocks such as increasing global food prices. J Nutr. 2010;140:162–9. Ruel MT, Garrett JL, Hawkes C, Cohen MJ. The food, fuel, and financial crises affect the urban and rural poor disproportionately: a review of the evidence. J Nutr. 2010;140:170–6. World Food Program. Hunger series: hunger and markets. World Food Program and Earthscan. 2009 [cited 2009 Jun 10]. Available from: http://www.wfp.org/content/world-hunger-series-hunger-and-markets. Fouéré T, Mair B, Delpeuch F, Martin-Prével Y, Tchibindat F, Adoua-Oyila G. Dietary changes in African urban households in response to currency devaluation: foreseeable risks for health and nutrition. Public Health Nutr. 2000;3:293–301. Bloem MW, de Pee S, Darnton-Hill I. Micronutrient deficiencies and maternal thinness: first chain in the sequence of nutritional and health events in economic crises. In: Bendich A, Deckelbaum RJ, editors. Preventive nutrition: the comprehensive guide for health professionals. 3rd ed. Totowa (NJ): Humana Press; 2005. p. 689–709. Thorne-Lyman AL, Valpiani N, Sun K, Semba RD, Klotz CL, Kraemer K, Akhter N, de Pee S, Moench-Pfanner R, et al. Household dietary diversity and food expenditures are closely linked in rural Bangladesh, increasing the risk of malnutrition due to the financial crisis. J Nutr. 2010;140:182–8. Koumou G, Subran L. Impact of high food prices on risk to food insecurity in Haiti. Rome: World Food Programme; 2008. Block SA, Kiess L, Webb P, Kosen S, Moench-Pfanner R, Bloem MW, Timmer CP. Did Indonesia’s crises of 1997/98 affect child nutrition? A cohort decomposition analysis of national nutrition surveillance data. Econ Hum Biol. 2004;2:21–44. Sanogo I. Global food price crisis and household hunger: a review of recent food security assessments. Humanitarian Practice Network. Humanitarian Exchange. 2009;42:8–12. Gitau R, Makasa M, Kasonka L, Sinkala M, Chintu C, Tomkins A, Filteau S. Maternal micronutrient status and decreased growth of Zambian infants born during and after the maize price increases resulting from the southern African drought of 2001–2. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8:837–43. Sztam KA, Fawzi WW, Duggan C. Macronutrient supplementation and food prices in HIV treatment. J Nutr. 2010;140:113–23. Sari M, de Pee S, Bloem MW, Sun K, Thorne-Lyman A, MoenchPfanner R, Akhter N, Kraemer K, Semba RD. Higher household expenditure on animal-source and nongrain foods lowers the risk of