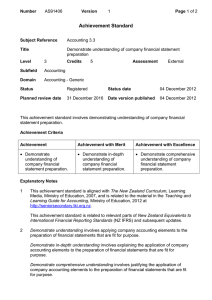

report on the performance of the new zealand qualifications

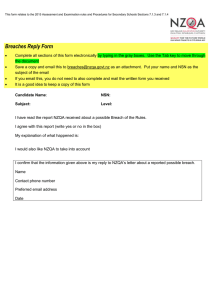

advertisement