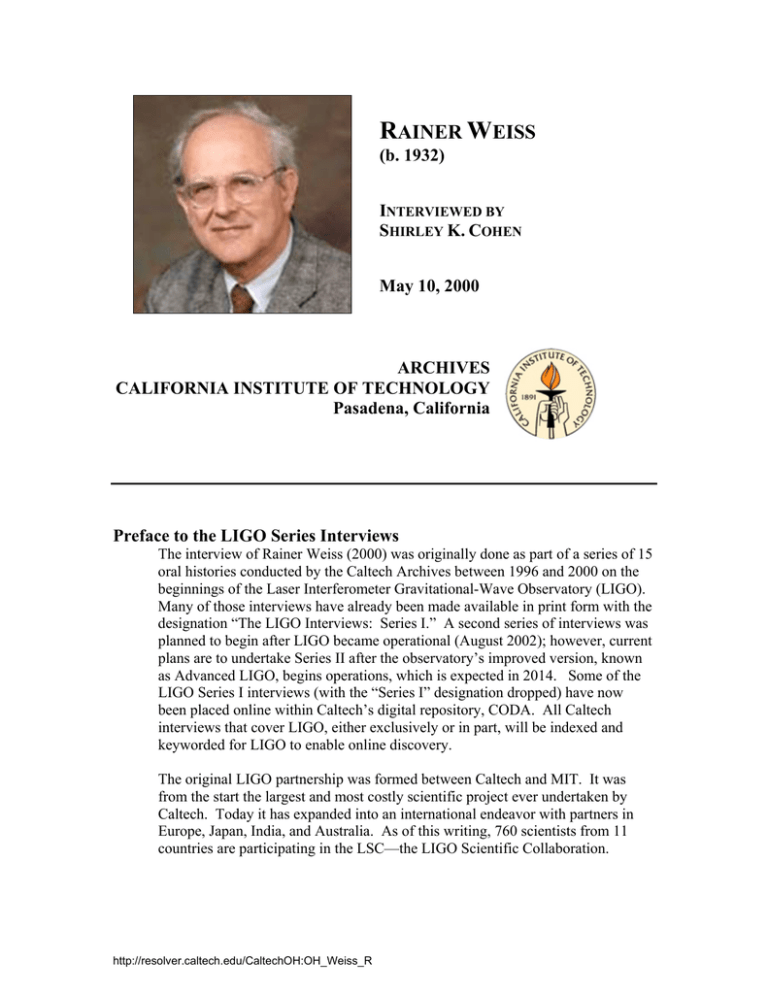

Interview with Rainer Weiss

advertisement