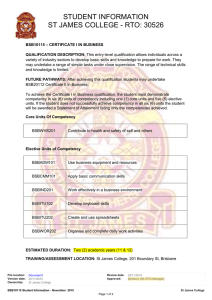

Training in security programs in Australia

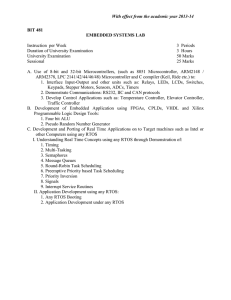

advertisement