Violence and Birth Outcomes: Evidence from Homicides in Brazil

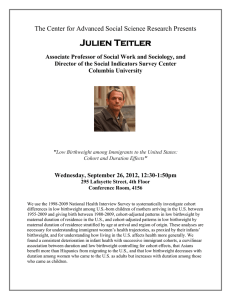

advertisement