Faecal carriage of CTX-M-15-producing Klebsiella

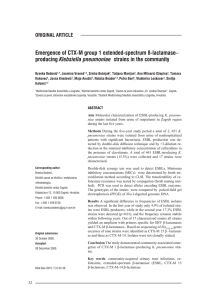

advertisement

[Downloaded free from http://www.ijmr.org.in on Tuesday, August 25, 2015, IP: 130.102.158.19] Indian J Med Res 129, May 2009, pp 599-602 Faecal carriage of CTX-M-15-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in patients with acute gastroenteritis Muzaheed, Yohei Doi*, J.M. Adams-Haduch*, C.T. Shivannavar*, D.L. Paterson*+ & S.M. Gaddad Department of Microbiology, Gulbarga University, Gulbarga, Karnataka, India, *Division of Infectious Diseases University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA & +University of Queensland, Royal Brisbane & Women's Hospital, Brisbane, Australia Received February 18, 2008 Background & objectives: Data on extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) produced by Gram-negative bacteria including Klebsiella pneumoniae especially molecular types of ESBL genes from India are limited. The present study was conducted to investigate the carriage and ESBL contents of multidrug-resistant K. pneumoniae recovered from patients with gastroenteritis in a rural village in southern India. Methods: Nine K. pneumoniae isolates obtained from 45 stool samples from patients with gastroenteritis from one rural and two urban sites, in southern India were included in the study. Antibiotic susceptibility testing, PCR analysis and sequencing were conducted to characterize the ESBL genes. Clonal relatedness was assessed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). Results: All the isolates were found to be resistant to at least one of the third generation cephalosporins tested. All the study isolates were confirmed to produce ESBLs. PCR and sequencing revealed the responsible gene to be blaCTX-M-15. blaTEM and blaSHV were absent. PFGE indicated that five of seven isolates from villagers were genetically closely related, and in turn were related to isolates from patients in two urban areas in this region. Interpretation & conclusions: Our findings showed that genetically-related isolates of K. pneumoniae producing CTX-M-15 were present in multiple areas in southern India. Larger studies need to be done in various geographical regions of the country to better define the molecular epidemiology of ESBLproducing K. pneumoniae and its clinical implications. Key words CTX-M-15 - extended-spectrum beta-lactamase - Klebsiella pneumoniae β-lactamases (ESBLs) is the most common mechanism of resistance to third-generation cephalosporins among Enterobacteriaceae including K. pneumoniae2,3. Infections caused by ESBL-producing organisms are difficult to manage for several reasons. First, empiric therapy consisting of β-lactam antimicrobials is Klebsiella pneumoniae is a successful opportunistic pathogen associated with various ailments such as urinary tract infections, septicaemia, respiratory tract infections and diarrhoea1. K. pneumoniae is part of commensal gastrointestinal flora in humans1. Production of extended-spectrum 599 [Downloaded free from http://www.ijmr.org.in on Tuesday, August 25, 2015, IP: 130.102.158.19] 600 INDIAN J MED RES, MAY 2009 often ineffective. Second, these organisms tend to be also resistant to other classes of antimicrobials including fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides2. CTX-M-type β-lactamases are increasingly becoming the predominant ESBLs globally in recent years, as opposed to the conventional TEM and SHV-type ESBLs2,3. Studies have reported high prevalence of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in India, where use of antimicrobials is relatively unrestricted. A study from northern India showed that 26 to 48 per cent of uropathogens belonging to Enterobacteriaceae were ESBL producers4. A recent report, from a hospital in rural southern India, described a high prevalence of ESBL producers5. Some reports have described the molecular epidemiology of ESBL producers, from the northern parts of the country6-8. Though presence of ESBLs in K. pneumoniae has been reported from India, there is scarce information on the molecular types from southern India5,8. From the limited data available, CTX-M-15 appears to be the predominant ESBL in northern India4,6-8. In the present study, we investigated the occurrence of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae carried by patients presenting with gastroenteritis in southern India. Material & Methods Bacterial isolates: A total of 45 stool samples were collected randomly from patients with gastroenteritis at three sites in Karnataka, southern India. Out of 45 samples collected, 43 were from Sedum, the other one each from Gulbarga and Raichur cities. K. pneumoniae was isolated from nine of these samples and included in the study. Seven were isolated from inpatients with diarrhoea in Sedum village in south India in August, 2005. The other two were isolated from patients with diarrhoea in the cities of Raichur and Gulbarga in August, 2005 and February, 2006, respectively. Basic microbiology work was done in Department of Microbiology, Gulbarga University, Gulbarga and molecular work was performed in Dr David L. Paterson Laboratory, Pittsburgh, USA. The susceptibility profiles of each study isolate were not known when the study was initiated. The village of Sedam is located in the northern part of Karnataka, 52 km away from the large regional center, Gulbarga. Raichur is 147 km away from Gulbarga. Antibiotic susceptibility testing: The antibiotic susceptibilities were determined by disk diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton agar plates (Beckton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA) as recommended by the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI)9. The disks containing the following antibiotics (µg) were used (Beckton Dickinson): cefoxitin (30), cefepime (30), ceftazidime (30), cefotaxime (30), ertapenem (10), imipenem (10), amikacin (30), gentamicin (10), ciprofloxacin (5) and chloramphenicol (30). ESBL screening and confirmation by phenotypic methods: The isolates showing reduced susceptibility to ceftazidime or cefotaxime or both were tested for ESBL production by double disk-diffusion test (DDDT) using four disks (µg): cefotaxime (CTX) (30), cefotaxime + clavulanic acid (10), cefatzidime (CAZ) (30), and ceftazidime +clavulanic acid (10). The inoculum and incubation conditions were the same as for standard disk diffusion recommendations. A ≥5 mm increase in zone diameter for either antimicrobial agent tested in combination with clavulanic acid versus its zone when tested alone was designated as ESBLpositive9. Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used as the control strain. PCR detection and sequencing of ESBLs: Genomic DNA was prepared by boiling the isolates and used as the templates for PCR reactions. Amplification of TEM, TEM SHV and CTXCTX M-type ESBL genes was performed on GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with primers and cycling conditions given in Table I10. The PCR Table I. Primers used for the study Gene blaSHV blaTEM blaCTX-M blaCTX-M-15 Source: Ref. 10 Primer SHV-F-S1 SHV-R-S2 TEM-F TEM-R CTX-M/F’ CTX-M/R’ CTXM15F CTXM15R Sequence 5’-ATTTGTCGCTTCTTTACTCGC-3’ 5’-TTTATGGCGTTACCTTTGACC-3’ 5’-ATGAGTATTCAACATTTCCGTG-3’ 5’-TTACCAATGCTTAATCAGTGAG-3’ 5’-TTTGCGATGTGCAGTACCAGTAA-3’ 5’-CGATATCGTTGGTGGTGCCATA-3’ 5’-CACACGTGGAATTTAGGGACT-3’ 5’-GCCGTCTAAGGCGATAAACA-3’ Annealing temperature (°C) Product size (bp) 60 1051 55 861 51 544 50 996 [Downloaded free from http://www.ijmr.org.in on Tuesday, August 25, 2015, IP: 130.102.158.19] 601 Muzaheed et al: FAECAL CARRIAGE OF ESBL PRODUCING K. PNEUMONIAE Table II. Characteristics of ESBL-producing isolates from stool samples of patients from southern India Isolate No. Location 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 236 Raichur Sedam Sedam Sedam Sedam Sedam Sedam Sedam Gulbarga CAZ CTX FEP FOX ETP IPM CIP C CN AM PCR PFGE TEM SHV CTX-M R R I I R R R R R R R R R R R R R R I R S S I R R I R S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S R R R R R R R R R R R S S R R R R R R R S S R R R R R R R S S R R I R R neg neg neg neg neg neg neg neg neg neg neg neg neg neg neg neg neg neg pos pos pos pos pos Pos pos pos pos A A B B A A A A A CAZ, ceftazidime; CTX, cefotaxime; FEP, cefepime; FOX, cefoxitin; ETP, ertapenem; IPM, imipenem; CIP, ciprofloxacin; C, chloromphenicol; CN, gentamicin; AM, amikacin. Suceptibility results were interpreted according to the CLSI criteria: R, resistance; I, intermediate; S, susceptible. neg, negative; pos, positive products were separated on 1 per cent agarose gels and visualized under UV light. The PCR products were purified with a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen,Valencia, CA, USA) and were sequenced on an ABI Prism 3100 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Genomic fingerprinting by pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE): Agarose plugs containing chromosomal DNA were prepared as described by Yuan et al11. The chromosomal DNA was digested overnight with 30 U of Xbal (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). PFGE was run in a CHEF-DRIII apparatus (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) at 6V/cm for 22 h. The pulse times were 5-40s. The banding patterns were interpreted according to the criteria of Tenover et al12. Results The results of antibiotic susceptibility tests indicated that all nine isolates in the study were resistant to cefotaxime and ciprofloxacin and intermediate or resistant to ceftazidime (Table II). Susceptibility to cefepime, chloramphenicol, gentamicin and amikacin was variable. All were susceptible to cefoxitin, ertapenem and imipenem. The inhibitory zones of cefotaxime and ceftazidime were increased in the presence of clavulanic acid by more than 5 mm in all isolates, which confirmed ESBL production. PCR analysis was positive for CTX-M-type ESBL gene in all nine isolates but negative for TEM and SHV-type β-lactamase genes. Upon sequencing, the deduced amino acid sequences of representative amplicons for CTX-M-type ESBL gene matched that of CTX-M-15. Fig. PFGE profile of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates recovered from stool samples (Lanes 31 to 37, K. pneumoniae from Sedam village; Lanes 30 and 236, K. pneumoniae from Raichur and Gulbarga, respectively; Lanes M, molecular weight marker). Macrorestriction polymorphism of genomic DNA determined by PFGE revealed the presence of two pulsotypes among the nine study isolates. Seven belonged to one and two the other (Fig.). The two isolates from Raichur and Gulbarga showed the same pulsotype with five of the seven isolates from Sedam (Table II, Fig.). Discussion Asymptomatic carriage of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae in the gastrointestinal tract may serve as the source of subsequent infections such as urinary tract infection13. Although the sample size was small in the study, isolates originating from stool were confirmed as ESBL producers. The results of our [Downloaded free from http://www.ijmr.org.in on Tuesday, August 25, 2015, IP: 130.102.158.19] 602 INDIAN J MED RES, MAY 2009 study revealed that K. pneumoniae producing CTXM-15 is already present in various geographic areas in southern India, as it has been observed in northern India6. CTX-M-15 is the predominant ESBL among E. coli causing community-associated infections worldwide3. It differs from CTX-M-3 by one amino acid substitution (Asp240 to Gly), which is known to extend the spectrum of activity to ceftazidime in addition to cefotaxime14. The isolates in the present study were all intermediate or resistant to ceftazidime, which is consistent with this enzymatic property of CTX-M-15. In addition to the cephalosporins all isolates were resistant to ciprofloxacin as well. Orally administered antimicrobials including ciprofloxacin are available over-the-counter and frequently used for the purpose of self-medication in India, which may account for the accumulation of multi-drug resistance among ESBL producing organisms15. Investigation of the mechanisms of ciprofloxacin resistance among the study isolates is underway. Of note, study isolates recovered from patients at three geographically distant sites shared identical macrodigestion patterns by PFGE. This finding suggests that a particular clone of K. pneumoniae may be associated with the spread of CTX-M-15 in southern India. Further studies are needed to determine the potential of this particular clone of CTX-M-15producing K. pnemoniae in causing communityassociated infections, as has happened with CTX-M15-producing E. coli. In conclusion, CTX-M-15-producing K. pneumoniae isolates from stool samples of patients with gastroenteritis in rural and urban areas in southern India were found, many of which belonged to a single clone. Hence routine diagnosis of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae should be done in hospitals, coupled with prudent use of antimicrobials to reduce propagation of multidrug-resistant and ESBL-producing organisms. References 1. Podschun R, Ullmann U. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin Microbiol Rev 1998; 11 : 589-603. 2. Paterson DL, Bonomo RA. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases: a clinical update. Clin Microbiol Rev 2005; 18 : 657-86. 3. Pitout JD, Laupland KB. Extended-spectrum β-lactamaseproducing Enterobacteriaceae: an emerging public-health concern. Lancet Infect Dis 2008; 8 : 159-66. 4. Khurana S, Taneja N, Sharma M. Extended spectrum βlactamase mediated resistance in urinary tract isolates of family Enterobacteriaceae. Indian J Med Res 2002; 116 : 145-9. 5. Navaneeth BV. Extended-spectrum and AmpC β-lactamases in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae from a rural South Indian tertiary care hospital. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2007; 29 : 602-3. 6. Ensor VM, Shahid M, Evans JT, Hawkey PM. Occurrence, prevalence and genetic environment of CTX-M β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae from Indian hospitals. J Antimicrob Chemother 2006; 58 : 1260-3. 7. Lal P, Kapil A, Das BK, Sood S. Occurrence of TEM & SHV gene in extended spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) producing Klebsiella sp. isolated from a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Med Res 2007; 125 :173-8. 8. Walsh TR, Toleman MA, Jones RN. Comment on: Occurrence, prevalence and genetic environment of CTX-M β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae from Indian hospitals. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007; 59 : 799-800; author reply 800-1. 9. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 17th informational supplement (M100-517). Wayne Pa: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2007. 10. de Oliveiva Garcia D, Doi Y, Szabo D, Adams-Haduch JM, Vaz TM, Leite D, et al. Multiclonal outbreak of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing extended-spectrum β-lactamase CTXM-2 and novel variant CTX-M-59 in a neonatal intensive care unit in Brazil. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008; 52 : 1790-3. 11. Yuan M, Aucken H, Hall LM, Pitt TL, Livermore DM. Epidemiological typing of klebsiellae with extended-spectrum β-lactamases from European intensive care units. J Antimicrob Chemother 1998; 41 : 527-39. 12. Tenover FC, Arbeit RD, Goering RV, Mickelsen PA, Murray BE, Persing DH, et al. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol 1995; 33 : 2233-9. 13. Kader AA, Kumar A, Kamath KA. Fecal carriage of extendedspectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in patients and asymptomatic healthy individuals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2007; 28 : 1114-6. 14. Poirel L, Gniadkowski M, Nordmann P. Biochemical analysis of the ceftazidime-hydrolysing extended-spectrum β-lactamase CTX-M-15 and of its structurally related βlactamase CTX-M-3. J Antimicrob Chemother 2002; 50 : 1031-4. 15. Sharma R, Sharma CL, Kapoor B. Antibacterial resistance: current problems and possible solutions. Indian J Med Sci 2005; 59 : 120-9. Reprint requests: Dr David L. Paterson, University of Queensland, Royal Brisbane & Women’s Hospital, Brisbane, Australia e-mail: david.antibiotics@gmail.com