on: platelet function analyzer (PFA)

advertisement

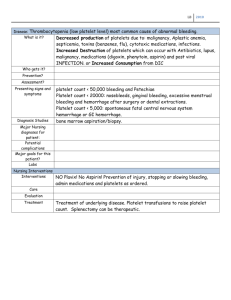

1426 Letters to the Editor 5 Gurbel PA, Bliden KP, Hayes KM, Yoho JA, Herzog WR, Tantry US. The relation of dosing to clopidogrel responsiveness and the incidence of high post-treatment platelet aggregation in patients undergoing coronary stenting. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 45: 1392–6. 6 Selvaraj CL, Van De Graaff EJ, Campbell CL, Abels BS, Marshall JP, Steinhubl SR. Point-of-care determination of baseline platelet function as a predictor of clinical outcomes in patients who present to the emergency department with chest pain. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2004; 18: 109–15. 7 Aleil B, Ravanat C, Cazenave JP, Rochoux G, Heitz A, Gachet C. Flow cytometric analysis of intraplatelet VASP phosphorylation for the detection of clopidogrel resistance in patients with ischemic cardiovascular diseases. J Thromb Haemost 2005; 3: 85–92. 8 Jilma B. Platelet function analyzer (PFA-100): a tool to quantify congenital or acquired platelet dysfunction. J Lab Clin Med 2001; 138: 152–63. 9 Golanski J, Pluta J, Baraniak J, Watala C. Limited usefulness of the PFA-100 for the monitoring of ADP receptor antagonists – in vitro experience. Clin Chem Lab Med 2004; 42: 25–9. 10 Mueller T, Haltmayer M, Poelz W, Haidinger D. Monitoring aspirin 100 mg and clopidogrel 75 mg therapy with the PFA-100 device in patients with peripheral arterial disease. Vasc Endovascular Surg 2003; 37: 117–23. 11 Ziegler S, Maca T, Alt E, Speiser W, Schneider B, Minar E. Monitoring of antiplatelet therapy with the PFA-100 in peripheral angioplasty patients. Platelets 2002; 13: 493–7. 12 Lepantalo A, Virtanen KS, Heikkila J, Wartiovaara U, Lassila R. Limited early antiplatelet effect of 300 mg clopidogrel in patients with aspirin therapy undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions. Eur Heart J 2004; 25: 476–83. 13 Grau AJ, Reiners S, Lichy C, Buggle F, Ruf A. Platelet function under aspirin, clopidogrel, and both after ischemic stroke: a case-crossover study. Stroke 2003; 34: 849–54. 14 Raman S, Jilma B. Time lag in platelet function inhibition by clopidogrel in stroke patients as measured by PFA-100. J Thromb Haemost 2004; 2: 2278–9. 15 Jilma B. Synergistic antiplatelet effects of clopidogrel and aspirin detected with the PFA-100 in stroke patients. Stroke 2003; 34: 849–54. 16 Gachet C. Regulation of platelet functions by P2 receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2006; 46: 277–300. 17 Turner NA, Moake JL, McIntire LV. Blockade of adenosine diphosphate receptors P2Y(12) and P2Y(1) is required to inhibit platelet aggregation in whole blood under flow. Blood 2001; 98: 3340–5. 18 Baurand A, Gachet C. The P2Y(1) receptor as a target for new antithrombotic drugs: a review of the P2Y(1) antagonist MRS-2179. Cardiovasc Drug Rev 2003; 21: 67–76. 19 Remijn JA, Wu YP, Jeninga EH, IJsseldijk MJ, van Willigen G, de Groot PG, Sixma JJ, Nurden AT, Nurden P. Role of ADP receptor P2Y(12) in platelet adhesion and thrombus formation in flowing blood. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2002; 22: 686–91. More on: platelet function analyzer (PFA)-100 closure time in the evaluation of platelet disorders and platelet function J . K O S C I E L N Y , * H . K I E S E W E T T E R * and G . - F . V O N T E M P E L H O F F *Institute for Transfusion Medicine, Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Charité, Berlin; and Clinic for Gynecology and Obstetrics, City Hospital of Ruesselsheim, Ruesselsheim, Germany To cite this article: Koscielny J, Kiesewetter H, von Tempelhoff G.-F. More on: Platelet function analyzer (PFA)-100 closure time in the evaluation of platelet disorders and platelet function. J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4: 1426–7. See also Hayward CPM, Harrison P, Cattaneo M, Ortel TL, Rao AK. Platelet function analyzer (PFA)-100 closure time in the evaluation of platelet disorders and platelet function. J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4: 312–9. We read with interest the recent review on the PFA-100 (PFA) by Hayward et al. (Working Group on PFA-100, ISTH-SSC Platelet Physiology Subcommittee) [1]. The article covers well the considerable body of literature pertaining to the use of PFA in detecting acquired and inherited platelet disorders. The various reports cited also show clearly that in most cases very few patients were studied, an indication that larger trials are needed in order to better assess the utility of PFA. Indeed, the Correspondence: J. Koscielny, Institute for Transfusion Medicine, Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Charité, Campus Charité Mitte, Schumannstr. 20–21, 10117 Berlin, Germany. Tel.: +49 45 052 5181; fax: +49 45 052 5906; e-mail: juergen.koscielny@charite.de Received 29 March 2006, accepted 4 April 2006 authors state that Ôadequately powered clinical studies…are required to establish a role for the PFA-100 [closure time (CT)] in predicting clinical outcomesÕ [1]. We agree, and that is why it came as a surprise to note their rather negative comment concerning the value of the PFA CT in preoperative assessment, referring to our recently published clinical trial data [2]. In fact, this study is in line with the Working Party’s recommendation, having been conducted with well over 5000 patients. In brief, we studied prospectively 5649 patients, administering a bleeding history and performing preoperative screening (including PFA testing) [2]. A negative bleeding history was found in 5021 (89%) patients, and among these individuals only nine (0.2%) had a positive screening test, all because of an abnormal activated partial prothromboplastin time (APTT). The remaining 628 (11%) patients had a positive bleeding history and/or evidence of impaired hemostasis, for example drug ingestion. Among these latter individuals, 256 (41%) had 2006 International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis Letters to the Editor 1427 Fig. 1. Patients with a positive bleeding history having either completely normal screening results or at least one abnormal screening test. Hemostatic disorders were determined by a battery of diagnostic tests including coagulation factor deficiency analysis, platelet aggregometry (ristocetin, ADP, collagen and arachidonic acid) and flow cytometry analysis for platelet glycoprotein abnormalities (CD41a, CD42b, CD61, CD62, CD63). (Coagulation: dysfibrinogenemia, n ¼ 1; factor VII deficiency, n ¼ 1). Patients in the group with negative bleeding history: 615 of 5021 (12.2%)* perioperative blood transfusions. *Chi-squared test after Pearson (asymptomatic significance doubleside): P ¼ 0.389 (not significant). PD, platelet disorder; VWD, von Willebrand disease; GT, Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia; BSS, Bernard-Soulier syndrome; coag, coagulopathy. at least one positive result with the following screening tests: complete blood count, PFA CT with collagen-epinephrine (CEPI) and collagen-ADP (CADP), prothrombin time and APTT. Of these screening tests, PFA CEPI CT was abnormal in 250 (98%) of the patients. In all 628 patients with a positive bleeding history and/or evidence of impaired hemostasis, for example drug ingestion, diagnostic testing for von Willebrand disease and platelet and coagulation disorders was performed as described on pages 197 and 198, and included comprehensive platelet aggregometry and flow cytometry studies [2]. Thus, a response to Hayward et al. [1] is warranted. The original Figs 1 and 2 from our study [2] have been modified and are shown here. Of the 628 patients with a positive bleeding history and/or evidence of impaired hemostasis, for example drug ingestion, 256 had a positive screening test, while 372 had a negative screening test. Diagnostic evaluation in the two groups revealed the various disorders as shown. It is noteworthy that none of the patients with a positive bleeding 2006 International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis history (and/or evidence of impaired hemostasis, e.g. drug ingestion) and a negative screening test was found to have any hemostatic disorder. However, the bleeding history and/or evidence of impaired hemostasis, for example drug ingestion was not highly suggestive in the majority of these patients. For example, the bleeding tendency was often related to an underlying disease rather than to a ÔtrueÕ bleeding disorder, for example nosebleeds in 59 patients with hypertension, gumbleeds in 45 patients with periodontitis, profuse menstruation in 18 patients with uterine myomas. On the other hand, the PFA-100 did not detect platelet dysfunction in 43 patients receiving antiplatelet drugs. Based on these findings and the screening results, we calculated the following sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values for CEPI CT: 90.8%, 86.6%, 81.8%, and 93.4%, respectively. Moreover, in our follow-up article [3] we showed that screening with CEPI CT enabled significant improvement of Ômeaningful clinical outcomesÕ. Patients with a positive bleeding history (and/or evidence of impaired hemostasis, e.g. drug ingestion) and a positive screening test (n ¼ 256) who were treated with dermopressin acetate (DDAVP) prior to surgery had the same transfusion needs as patients with a negative (n ¼ 5021) or positive bleeding history (and/or evidence of impaired hemostasis, e.g. drug ingestion) (n ¼ 372) but negative screening test who were not treated with dermopressin acetate (DDAVP) (Fig. 1). This contrasts dramatically with a similar group of patients with a positive bleeding history (and/or evidence of impaired hemostasis, e.g. drug ingestion) and abnormal CEPI CT, from an earlier companion study (n ¼ 5102), who were not pretreated with DDAVP [3]. These patients experienced 8-fold more transfusion needs than patients with a negative bleeding history and normal CEPI CT (P < 0.001). Therefore, from these two studies on preoperative assessment with more than 10 000 patients [2,3], it can be concluded that the PFA-100 CEPI test meets the requirements both as a useful tool for screening and possible predicting clinically relevant bleeding. References 1 Hayward CPM, Harrison P, Cattaneo M, Ortel TL, Rao AK. Platelet function analyzer (PFA)-100 closure time in the evaluation of platelet disorders and platelet function. J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4: 312–9. 2 Koscielny J, Ziemer S, Radtke H, Schmutzler M, Pruss A, Sinha P, Salama A, Kiesewetter H, Latza R. A practical concept for preoperative identification of patients with impaired primary hemostasis. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2004; 10: 195–204. 3 Koscielny J, von Tempelhoff G-F, Ziemer S, Radtke H, Schmutzler M, Sinha P, Salama A, Kiesewetter H, Latza R. A practical concept for preoperative management of patients with impaired primary hemostasis. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2004; 10: 155–66.