THE INTERSECTION BETWEEN THE BUILDING ACT

advertisement

AT THE CROSSROADS: THE INTERSECTION BETWEEN THE BUILDING ACT

AND THE RESOURCE MANAGEMENT ACT

Ashley Cornor, Senior Associate, DLA Phillips Fox

Introduction

It has been a busy first term for the National-led government. The regulatory reform agenda

has extended into a number of complex areas, including both building control and resource

management. In the latter arena, National's commitment to have a bill amending the

Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA) before Parliament in its first 100 days in office was

answered by the 'Phase 1' RMA reforms that subsequently took effect as the Resource

Management (Streamlining and Simplifying) Amendment Act 2009.

'Phase 2' of the reforms is now in full swing, with the express intention of achieving least cost

delivery of good environmental outcomes. Ten focused workstreams have been developed to

facilitate this. In amongst them is a dedicated workstream - RMII B - which involves an express

evaluation of the interface between the RMA and the Building Act 2004 (BA04).

The purpose of this paper is to examine the supposed justifications for RMII B and to provide an

update as to progress of the reform package. It is structured in the following way:

Part 1

describes the current statutory environment and the essential characteristics of the

RMA and BA04 consenting regimes, as they apply to building work.

Part 2

identifies the perceived problems with the current statutory environment and

describes the reforms that propose to address it.

Part 3

examines the progress of the reforms to date.

Part 4

considers how the reforms might evolve from here, and what is on the horizon as far

as co-management of the RMA and BA04 regimes is concerned.

1

Status quo

Building projects in New Zealand are currently subject to both the RMA and the BA04: the two

regimes run in parallel. This applies regardless of whether a consent is required under either or

both pieces of legislation, although in practice the application of either is fairly muted where

consents are not required.

The overlap of the two statutes is usually justified on the basis that they serve quite different

functions. As Tipping J observed in Christchurch International Airport Limited v Christchurch

City Council [1997] NZRMA 145, 148 (HC):

Reduced to the simplest level relevant to the present case, the Building Act allows a

Council to control building work in the interests of ensuring the safety and integrity

of the structure, whereas the Resource Management Act allows the Council to

impose controls from the point of view of the activity to be carried out within the

structure and the effect of that activity on the environment and of the environment

on that activity.

348351_1

Put crudely, the distinction is one of concern with building performance (the BA04's domain) as

opposed to the impact of a building on the wider environment (the RMA's concern).

Before turning to look at the key features of both regimes, it is illustrative to quickly chart their

respective beginnings to see how this parallel regulatory approach has evolved.

Building controls in New Zealand

Building on hard lessons learned in various European fire or earthquake-related catastrophes,

New Zealand was a relatively early adopter of building controls following the execution of the

Treaty of Waitangi.

The Raupo Houses Ordinance of 1842 imposed a financial penalty on buildings constructed

wholly or in part of various flammable materials. Originally applicable in Auckland, the

Ordinance was subsequently brought into effect throughout New Zealand. It was soon to be

complemented by various region/area specific refinements, which imposed additional local

controls. Of these, the Dunedin Building Ordinance 1862 remained in force until 15 September

1993.1

These early ordinances shared a general concern with protecting built-up areas from mass

destruction in the event of fire or other types of disaster. It was not until the inception of the

Municipal Corporation Act 1876 that local government was given more general powers in

relation to building control matters. Under this statute and subsequent replacements, the

system of building bylaws that guided building control in New Zealand for most of the Twentieth

Century was developed. For example, under the Municipal Corporations Act 1954, local

authorities were empowered to make bylaws:2

Regulating and controlling the construction, alteration, and repair of buildings as

defined in the bylaws, including the design, construction, alteration, and repair of

buildings in relation to their resistance to earthquake shocks.

Council bylaw making powers found ultimate expression in the New Zealand Standard Model

Building Bylaw - NZS1900. They were supported in this period by the functions of numerous

other Government departments and statutory bodies (e.g. electrical supply authorities). The

resulting system involved the prescription of specific details for different construction techniques

and generally entailed the issue of a building permit, with separate plumbing and drainage

permits.

Concern expressed during the 1980s about complexity, inefficiency, stymying of innovation,

lack of consistency, and process-cost in the building control regime (sound familiar?) lead to a

move away from the prescriptive regional model to one based on a nationwide, standard,

performance-based building code. This concept was enshrined at the heart of the Building Act

1991 and still powers the BA04 today.

The key point arising is that throughout these sequential developments in building control, the

focus has largely been on the qualities and characteristics of the building (or building work)

1

Building Amendment Act 1993, section 24(1).

2

Municipal Corporations Act 1954, section 386(14).

348351_1

2

concerned. The approach is founded on a concern to ensure that buildings do not endanger

their occupants or pose a risk to buildings and people on other property.

Environmental controls in New Zealand

As in the building control sphere, New Zealand has a long history of regulating the

environmental consequences of the use of land and water resources. The pattern of local

control of these issues is evident again, with locally appointed boards and area-specific statutes

empowering controls on matters such as soil and water conservation and land drainage.

'Town planning' in any semblance of its modern form entered the scene with the Town Planning

Act 1926. That statute required borough councils representing a population of more than 1,000

people to develop town planning schemes, which were intended to allow the city or borough to

develop 'in such a way as will most effectively tend to promote its healthfulness, amenity,

convenience, and advancement'.3 Powers were provided to restrict the construction of

buildings that would be inconsistent with an approved town planning scheme. Property

occupiers were able to object to the provisions of a proposed town planning scheme to a

centralized Town-planning Board,4 establishing the expected right of public participation in

planning matters that remains characteristic of the RMA today.

Under this system, there was clearly some overlap between the broad purposes of town

planning schemes and the built environment. However, town planning schemes did not

descend into the detail of building construction or performance. Instead, they were concerned

with what modern planners would probably refer to as 'bulk and location' and 'urban design'

controls. The list of permissible considerations set out in the Schedule to the Town Planning

Act 1926 is illustrative:

Matters to be dealt with in Town and Extra-urban planning schemes

…

2.

Buildings, with particular reference to their position on allotment [sic] and

in relation to any road or street or to other buildings, their density,

character, height, harmony in design of facades.

The division of environmental controls in this way continued through to the late 1980s, with

successive iterations of each of the relevant statutes. However, as was the case in relation to

building control, concerns had been brewing about the efficiency and effectiveness of this

disparate approach to environmental matters. Spurred by a decade or so of new international

thinking about integrated management of environmental issues, the Labour Government of the

late 1980s introduced a bill to Parliament that would eventually become the RMA (passed into

law under the next National Government), with some matters divided off to be dealt with under

other legislation such as the Crown Minerals Act 1991 and, later, the Hazardous Substances

and New Organisms Act 1996 and the Fisheries Act 1996. The RMA is frequently heralded as

legislation that repealed 78 statutes and regulations, and amended numerous others, to provide

a single piece of legislation for the management of land, water, soil and air throughout New

Zealand.

3

Town Planning Act 1926, section 3(1).

4

Town Planning Act 1926, section 17(3).

348351_1

3

While the environmental controls referred to above varied in accordance with their particular

subject matter or geographic extent of application, they had a common characteristic: namely, a

general lack of concern about building performance, save to the extent that buildings had some

impact ('externalities' in planning jargon) on their surroundings.

The situation today: key features of the RMA and the BA04

The RMA came into force on 1 October 1991, closely followed by the Building Act 1991 on

1 July 1992. The BA04 repealed and substituted the Building Act 1991 for all effective

purposes from 31 March 2005.

The key features of each piece of legislation are compared (in very broad terms) in the table

that follows.

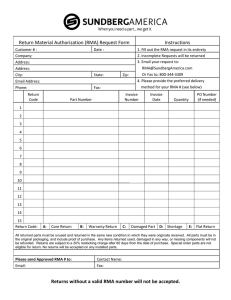

Key features

RMA

BA04

Fundamental concern

Promoting the sustainable

management of natural and

physical resources (i.e. land,

water, air, soil, minerals,

energy, plants and animals,

AND structures)

Regulating building work,

establishing a licensing regime

for building practitioners, and

setting performance standards

for buildings, for health and

safety reasons and to promote

sustainable development

National or local

Some national direction, with

most direct regulation through

regional and district/city plans

National building code, locally

administered

Consent requirements

'Permitted' may be carried out

as of right, other types of

activity require resource

consent

All building work must comply

with building code, but some

building work is exempt from

the need for a building consent

Who applies for consent

Anyone can apply for consent

for an activity on any land

'Owners' apply for consent

Public participation

In plan development and

selected resource consent

processes

No public participation

Right of appeal

Generally to Environment

Court, although an 'objection'

process also exists

To Chief Executive of the

Department of Building and

Housing, through the

determination process

The current system maintains the fundamental historical distinction between controlling the

impacts of structures on the wider environment (RMA) and performance of structures in and of

themselves (BA04). That said, overlaps can and do occur, as a further quote from Tipping J in

the Christchurch International Airport case illustrates:

For the purposes of granting building consents [the Building Act] prevails and

different territorial authorities cannot impose their own requirements on top of or in

substitution for the [building code]. If, however, the territorial authority is facing a

particular planning or resource management issue, whose appropriate solution lies

348351_1

4

in the imposition of a requirement going beyond the [building code], [the Building

Act] does not prevent that course. This will not give territorial authorities carte

blanche to supplement or depart from the building code, which is clearly intended,

within its proper compass, to have national application. The construction which I

prefer simply allows the building code to be exceeded when resource management

considerations justify such a departure.

Tipping J was referring to the situation where a local authority finds it necessary to impose

indirect controls on the performance of a building through a district plan or the resource consent

process. That requires an evaluative judgment on the part of the consent authority in each

case. However, there are other situations where links between the RMA and the BA04 are

express. These are identified below.

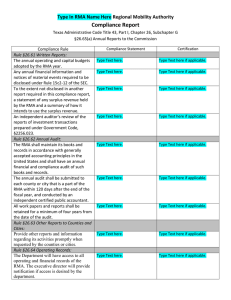

Express cross-references

The table that follows summarises the relatively limited number of express cross-references

between the RMA and the BA04.

References to the BA04 in the RMA

References to the RMA in the BA04

Section 10B

Section 10

Provides some protection for building work that

was the subject of a building consent issued at a

time when no resource consent was required for

the building work, but where the district plan is

subsequently changed to impose such a

requirement. An extension of the usual 'existing

use rights' concept.

Definition of 'allotment' refers back to subdivision

concepts arising from the RMA. Note that the

definition of allotment in this provision differs in

some important respects from that in section 218

of the RMA, which is a cause of some

administrative difficulty in the context of some

provisions of the BA04.

Section 68

Section 37

Allows rules in regional plans to provide for the

protection of 'other property' from the effects of

surface water, which require people undertaking

building work to achieve performance criteria

additional to, or more restrictive than, those

specified in the building code.

Provides for a territorial authority to tag a project

information memorandum with a certificate to the

effect that building work also needs to be the

subject of a resource consent, and that building

work cannot proceed until such a consent is

obtained.

Section 76

Section 116A

As above, but in relation to district rather than

regional plans.

Prevents a territorial authority from issuing a

certificate under section 224(f) of the RMA

unless it is satisfied that the building concerned

will comply to a stated degree with various

clauses of the building code (escape from fire,

disabled facilities/access, and protection of 'other

property') and that its performance in relation to

the other clauses of the building code will not be

any worse.

Section 224

Cross-reference to the need for compliance with

selected clauses of the building code where a

subdivision of an existing building (e.g. by way of

unit titling or a cross-lease) is proposed.

348351_1

5

What are the implications of all this?

For most people looking at carrying out building work, the main implication of the current

system is that more than one piece of paper may be required from the local council before work

can commence. Experience suggests that this is often a surprise for landowners, especially in

the context of domestic works where the proponent may have little or no experience of building

projects and consent processes. In addition, the range of ancillary requirements that are also

imposed under the likes of local authority bylaws can further create the impression of

bureaucratic overkill that sits behind the National Government's drive to reform the

environmental and building regulatory regimes.

For most projects that trigger both resource and building consent requirements, the usual

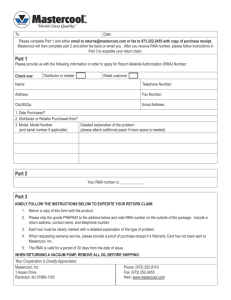

process resembles the following:

Conceptual

design

Resource

consent

application

Developed

design and

working

drawings

Building

consent

application

In part, this reflects the significant alterations to a project that can be made through the

resource consent process in response to the qualitative views expressed by councils and other

decision-makers and also in light of concessions made on account of public submissions.

There are logical and historical justifications for the stratified approach to these issues that is

characteristic of the current system. Many applicants are not required to come to grips with

those distinctions for the purposes of their proposed works, meaning that the spectre of multilimbed bureaucracy is often heightened and the lack of a sensible-seeming 'one stop shop'

loudly lamented. Whether this situation should be, or even can be, addressed is one of the

most significant questions for this aspect of the RMA and BA04 reforms.

2

Genesis and aim of the reforms

Consultation initiated by the Government as part of the development of the Phase 2 RMA

reforms resulted in some commentary on the integration (or lack thereof) between the RMA and

the BA04.

Key concerns that were identified include:5

•

consistency of standards and definitions applying to the RMA and the BA04;

•

consistency of conditions applied to building and resource consents;

•

risk-averse culture and practice of local authorities relating to potential liability for

claims under the BA04 and costs under the RMA;

5

Hon Dr Nick Smith, Minister for the Environment, report to the Cabinet Economic Growth and

Infrastructure Committee, 'Progress on Phase Two of the Resource Management Reforms' (2009),

available at http://www.mfe.govt.nz/cabinet-papers/progress-phase-two-resource-managementreforms.html (last accessed 12 July 2011).

348351_1

6

•

inconsistency of district plan controls on residential activities;

•

inability for minor RMA technical compliance issues to be addressed as part of the

building consent process;

•

lack of links between permitted activities under the RMA and building consent

exemptions under the BA04;

•

lack of public understanding of the difference between resource consents and

building consents.

Discussions with Ministry for the Environment (MFE) staff indicate that work is currently being

carried out to evaluate these issues and to determine where the problems actually lie. While

the official view is pending, anecdotal experience suggests that the significant themes emerging

are:

1

inconsistency (i.e. between statutes and also with regard to the way each statute is

interpreted and applied in different parts of the country);

2

a perception of unnecessary duplication;

3

unresponsiveness of one statutory regime to the other;

4

lack of public understanding of the parallel building and resource consent processes.

The RMII B workstream has been set up to respond to these concerns in three particular ways.

•

First, it will identify ways to align and streamline processes for approving resource

and building consents where both are required for a building. It is specifically

envisaged that this could extend to joint (or at least aligned) processes for a defined

range of building work.

•

Second, the workstream will look for opportunities to improve consistency between

the RMA and the BA04.

•

Third, it will seek ways of improving public understanding of both statutory regimes

and how they interoperate.

This aligns with some of the objectives of the DBH's BA04 reform workstreams. In particular,

one of the papers prepared by Hon Maurice Williamson, the Minister of Building and

Construction, has identified the following characteristic as one of the necessary facets of an

efficient, productive and accountable building sector:6

Seamless integration with resource management and local planning, and other

related activities.

There is no direct discussion in the Minister's paper as to how this might be achieved.

6

Hon Maurice Williamson, Minister of Building and Construction, Cabinet paper, 'Building Act

Review 5: Delivering building regulation' (2010), available at

http://www.dbh.govt.nz/UserFiles/File/Building/Building%20law%20and%20compliance/Paper-5Delivering-bilding-regulation.pdf (last accessed 13 July 2011), at paragraph 4.

348351_1

7

It is now time to examine how far the reforms have come since the RMII B programme was

announced in 2009.

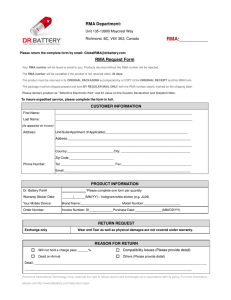

3

Progress of the reforms

Discussions with MFE and DBH staff indicate that the RMII B reforms are being divided

between the two entities. For the MFE's part, efforts are currently directed towards clearly

identifying the problems with the current system and formulating different options to address

them. At this stage, the level of the work is described as 'developmental'. It is understood that

MFE staff hope to report back to the Minister with options in early 2012, with decisions to follow

about the nature and scope of any industry/community consultation on the proposals.

In May of this year, the Minister for the Environment reported back to the Cabinet Business

Committee as to general progress with the Phase 2 RMA reforms. This included an indication

as to progress with RMII B. In that regard, the Minister's report states:7

Work stream

RMII B

Description

Alignment of consenting

processes under the RMA and

the Building Act 2004

Progress to date

Initial proposals have been

taken forward under the

Building Act reforms

With respect, it is difficult to see how any reconciliation of RMA and BA04 processes has been

manifested through the BA04 reforms revealed to the public to date. Certainly, the Building

Amendment Bill (No 3) (253-2) that was reported back from the Local Government and

Environment Select Committee on 28 June 2011 does little to expressly or implicitly align RMA

and BA04 processes, considerations, or spheres of control.

As at the time of drafting this paper, further inquiries are being made with the DBH to determine

whether there are RMA-related reforms proposed as part of the further BA04 amendments that

are likely to be publicised before the end of 2011. To date, nothing has been publicly revealed

about progress toward the three targets of the RMAII B workstream that are discussed above.

4

Where to from here?

The ultimate aspirational outcome of a RMA/BA04 alignment process is arguably a single, onestop shop consent that covers both pieces of legislation. However, the variances in focus and

feature that currently characterise the two regimes impose a significant practical divide that

makes such a prospect untenable at the moment. In particular, reconciling the flexibility of

outcome inherent in the RMA process with the demands for detailed, certain design called for

under the BA04 looms as a challenge. It is also important not to lose sight of the fact/problem

that both statutes provide a range of tools other than resource/building consents to authorise

activities or buildings. Examples include the designation process under the RMA and the

certificate of acceptance under the BA04. The implications of a unified consenting approach for

these mechanisms would also require careful examination.

7

Above n 5, at paragraph 18.

348351_1

8

To bridge that divide, fundamental changes will be required in the operation of both regimes.

Alternatively, if the proposition were to simply bolt both pieces of legislation together resulting in

a single drawn out process with a single piece of paper at the end, significant changes in

industry and project management practices would arguably be required. Most likely, it would

take elements of both.

The aspirational target of a unified consent should also not be taken as a given. Serious

questions must be asked about whether the concerns identified as part of the Phase 2 RMA

reforms are real and systemic, or merely perceived and anecdotal. Do they stem from interface

difficulties between the RMA and BA04 regimes, or are they in fact symptoms of one or the

other not performing efficiently? Will the apparent push for increased regionalisation of both

environmental and building control administration mitigate the problems in any event? These

are some of the challenging issues that it appears the MFE and the DBH are currently grappling

with.

That said, there are some areas where less wholesale change is perhaps both feasible and

desirable. Candidates include:

•

Closer alignment of permitted activities under the RMA (through the use of national

environmental standards, to provide centralised direction to local authorities) and

building work that is exempt from consent requirements under Schedule 1 of the

BA04.

•

The potential for close alignment between some of new building consent categories

proposed as part of the current reforms (e.g. the low-risk building consent) and

existing types of RMA consent (e.g. controlled or restricted discretionary consents).

•

The possibility that the two regimes might be more responsive to one another: for

example, a minor variation approved as part of a building consent process could also

include consideration and (if appropriate) approval of an amendment to the related

resource consent, removing the difficulty of changes desirable under one regime

being blocked by the difficulties associated with amending consents under the other.

•

Reconciliation of minor discrepancies between the two statutes, such as their slightly

different definitions of 'allotment', that simply cause administrative difficulties for

consent authorities.

There will also always be scope for local authorities to improve the customer service experience

they offer. The biggest challenge in this regard is to generate a feeling that people are dealing

with a single entity, rather than disparate departments administering separate regimes with little

effective communication between them. No legislative reforms are required for improvements

in this regard.

It will be interesting to observe as elements of the RMII B workstream find expression in the

BA04 reform process. For the time being, it is simply a case of 'watch this space'.

348351_1

9