REVIEWS

TIBS 24 – FEBRUARY 1999

Non-mitochondrial ATP

transport

Herbert H. Winkler and

H. Ekkehard Neuhaus

Exchange of organelle ATP with cytosolic ADP through the ADP/ATP carrier is

a well-characterized feature of mitochondrial metabolism. Obligate intracellular bacteria, such as Rickettsia prowazekii, and higher-plant plastids possess another type of adenylate transporter, which exchanges bacterial or

plastidic ADP for ATP from the eukaryotic (host cell) cytoplasm. The bacterial

and plastidic transporters are similar but do not share significant sequence

similarities with the mitochondrial carrier. Recent molecular and biochemical

studies are providing deeper insight into the functional and evolutionary

relationships between the bacterial and the plant transport proteins.

THE CONCENTRATION OF ATP within

cells is orders of magnitude higher than

we would predict from the equilibrium

constant for ATP hydrolysis. The synthesis of ATP at such a high concentration

and the use of this ATP as the common

energy currency are a large part of cellular metabolism. The size and charge of

ATP prevents its crossing biological membranes without a carrier protein. Because

ATP is essentially absent from the extracellular environment, and the precious

ATP pool within the cytoplasm would be

put at risk if an ATP carrier was present

in the cell membrane, plasma-membrane

ATP transporters have not evolved. Thus,

conventional wisdom supports the generalization that the cell membrane is impermeant to ATP. However, the internal

membranes of the cell, organelle membranes, are not included in this generalization, and the cell membranes of strange

creatures that inhabit the cytoplasm of

other cells are also an exception. These

membranes, in contrast to the typical

cell membrane, separate an external

compartment where ATP is an available

substrate from an internal compartment

where ATP would be beneficial.

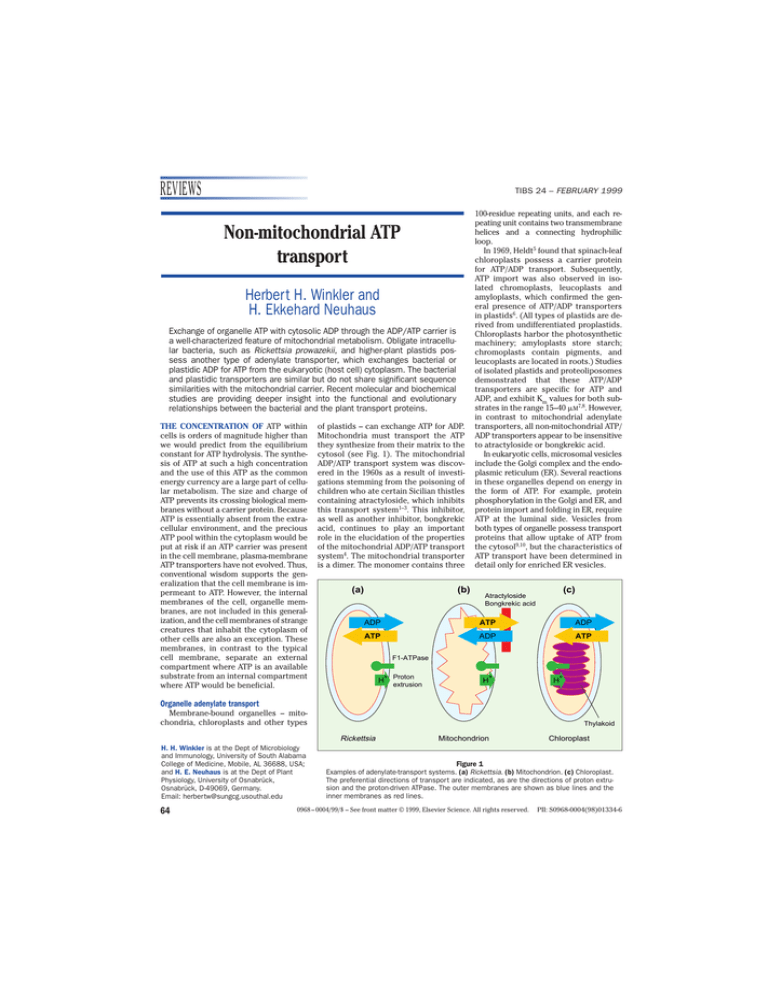

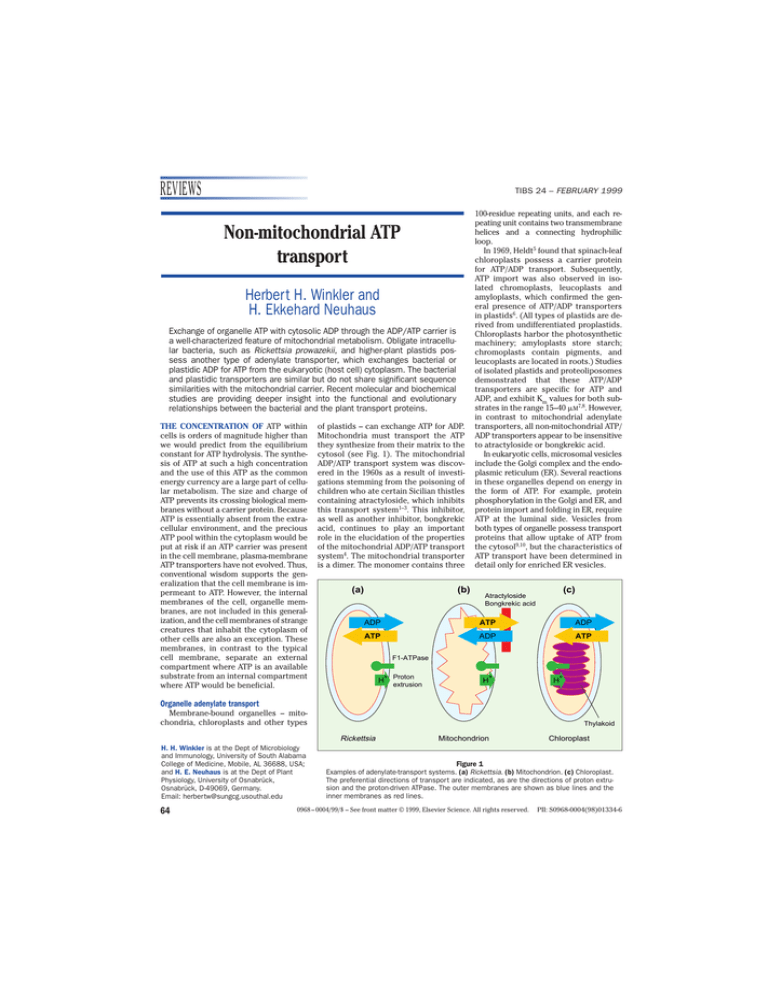

of plastids – can exchange ATP for ADP.

Mitochondria must transport the ATP

they synthesize from their matrix to the

cytosol (see Fig. 1). The mitochondrial

ADP/ATP transport system was discovered in the 1960s as a result of investigations stemming from the poisoning of

children who ate certain Sicilian thistles

containing atractyloside, which inhibits

this transport system1–3. This inhibitor,

as well as another inhibitor, bongkrekic

acid, continues to play an important

role in the elucidation of the properties

of the mitochondrial ADP/ATP transport

system4. The mitochondrial transporter

is a dimer. The monomer contains three

(a)

(b)

100-residue repeating units, and each repeating unit contains two transmembrane

helices and a connecting hydrophilic

loop.

In 1969, Heldt5 found that spinach-leaf

chloroplasts possess a carrier protein

for ATP/ADP transport. Subsequently,

ATP import was also observed in isolated chromoplasts, leucoplasts and

amyloplasts, which confirmed the general presence of ATP/ADP transporters

in plastids6. (All types of plastids are derived from undifferentiated proplastids.

Chloroplasts harbor the photosynthetic

machinery; amyloplasts store starch;

chromoplasts contain pigments, and

leucoplasts are located in roots.) Studies

of isolated plastids and proteoliposomes

demonstrated that these ATP/ADP

transporters are specific for ATP and

ADP, and exhibit Km values for both substrates in the range 15–40 mM7,8. However,

in contrast to mitochondrial adenylate

transporters, all non-mitochondrial ATP/

ADP transporters appear to be insensitive

to atractyloside or bongkrekic acid.

In eukaryotic cells, microsomal vesicles

include the Golgi complex and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Several reactions

in these organelles depend on energy in

the form of ATP. For example, protein

phosphorylation in the Golgi and ER, and

protein import and folding in ER, require

ATP at the luminal side. Vesicles from

both types of organelle possess transport

proteins that allow uptake of ATP from

the cytosol9,10, but the characteristics of

ATP transport have been determined in

detail only for enriched ER vesicles.

(c)

Atractyloside

Bongkrekic acid

ADP

ATP

ADP

ATP

ADP

ATP

F1-ATPase

+ Proton

H

extrusion

+

H

+

H

Organelle adenylate transport

Membrane-bound organelles – mitochondria, chloroplasts and other types

Thylakoid

Rickettsia

H. H. Winkler is at the Dept of Microbiology

and Immunology, University of South Alabama

College of Medicine, Mobile, AL 36688, USA;

and H. E. Neuhaus is at the Dept of Plant

Physiology, University of Osnabrück,

Osnabrück, D-49069, Germany.

Email: herbertw@sungcg.usouthal.edu

64

Mitochondrion

Chloroplast

Figure 1

Examples of adenylate-transport systems. (a) Rickettsia. (b) Mitochondrion. (c) Chloroplast.

The preferential directions of transport are indicated, as are the directions of proton extrusion and the proton-driven ATPase. The outer membranes are shown as blue lines and the

inner membranes as red lines.

0968 – 0004/99/$ – See front matter © 1999, Elsevier Science. All rights reserved.

PII: S0968-0004(98)01334-6

REVIEWS

TIBS 24 – FEBRUARY 1999

Uptake of ATP into enriched ER vesicles from rat liver and bakers’ yeast is

protein mediated and exhibits micromolar apparent-affinity constants10,11. As

observed for mitochondrial adenylate

transport, movement of adenylates into

the lumen of enriched ER is associated

with counterexchange11,12. However, unlike the mitochondrial ADP/ATP transporter, the ER ATP/ADP-transport system

was not inhibited by carboxyatractylate10,11. This suggests that the two transporters exhibit substantial structural differences. ER vesicles enriched from a

bakers’-yeast mutant that lacks the ERmembrane-bound Sac1p protein exhibit

strongly reduced rates of ATP import12.

From this observation, it was logical to

assume that Sac1p is an adenylate transporter. However, because Sac1p possesses only one putative transmembrane domain13, one would have to

assume a rather unusual topology for

this to be a solute transporter. Indeed, a

detailed alignment of the amino acid sequence of Sac1p with those of other proteins suggested that Sac1p performs

a function similar to an inositol-5phosphate phosphatase14; no connection

between such a function and the ER ATP

transporter has been reported.

Bacterial adenylate transport

In 1976, Winkler15 reported that the bacterium Rickettsia prowazekii, a pathogenic invader of eukaryotic cell cytoplasm

and the etiologic agent of louse-borne typhus, transports ATP – the first report of a

strange intracytoplasmic creature’s benefiting from an adenylate-transport system. There is no net transport of adenylates into rickettsiae by this system;

rather, these bacteria obtain energy

through the obligate exchange of ATP for

ADP. The transport system exhibits a halfmaximal velocity at a substrate concentration of ~75 mM and is highly specific in

that deoxyribonucleotides, AMP and nonadenine-based ribonucleotides are not

substrates; specificity resides in the base,

the number of phosphates and the sugar.

In 1982, Hatch and co-workers16 showed

that the bacterium Chlamydia psittaci

possesses a similar ATP/ADP transport

system. Both of these bacterial species

are obligate intracellular parasites. R.

prowazekii can grow only within the cytoplasm of a eukaryotic host cell, and

chlamydiae can grow only within special

intracytoplasmic vacuoles. Thus, the evolutionary acquisition of such a transport

system in these bacteria allowed them

to parasitize the energy reserves of their

host. None of the genomic sequences

currently available encode a protein that

is homologous to that in mitochondria,

rickettsiae, chlamydiae or plastids (see

below).

Differences in preferred directions of

exchange

Mitochondrial transporters differ from

plastidic and rickettsial transporters in

their preferred direction of ATP transport (see Fig. 1). In the test tube, all

possible directions of exchange of ATP

and ADP are observed. However, in situ

there is a single preferred and productive direction. Rickettsiae and chlamydiae take ATP from the host cell cytoplasm, use the ‘high-energy phosphate’

and return ADP, which the host cell

recharges to ATP. By contrast, mitochondria provide the cytoplasm with ATP17.

Unlike mitochondrial ATP, the ATP

generated in chloroplasts through

photosynthesis is not available to the

cytoplasm but is totally consumed by

CO2 fixation and other anabolic processes

that take place within the interior of the

chloroplast. Transport studies on isolated

chloroplasts revealed that ATP import

occurs twice as fast as ADP uptake7. In the

case of heterotrophic pea-root plastids,

uptake of ATP and ADP occurs at similar

rates7, which indicates that the cytosolic

ATP:ADP ratio is important for control of

anabolic reactions in storage plastids.

Although strict control of adenylatetransport polarity might be limited to

mitochondria, in both rickettsiae and

plastids the ATP influx appears to be the

favoured direction, because cytosolic

ATP:ADP ratios are high.

Sequences of bacterial and plastidic

transporters

The gene that encodes the rickettsial

adenylate transporter (tlc) was sequenced in 1989; on the basis of the deduced amino acid sequence, we can predict that the rickettsial protein is twice as

large as (56.7 kDa), and shares no meaningful sequence homology with, its mitochondrial analogues, although both are

typical membrane proteins18. The rickettsial transporter has 12 predicted

transmembrane domains and, unlike the

mitochondrial transporter, has no repeating elements. Peptide-specific-antibodyaccessibility experiments place the

C-terminus in the rickettsial cytoplasm19.

In 1995, Kampfenkel et al.20 identified an

Arabidopsis thaliana cDNA that encodes a

protein that shares .66% similarity with

the rickettsial ATP/ADP transporter but

lacks any sequence relationship with mitochondrial adenylate transporters. The

surprisingly high degree of similarity to

a prokaryotic protein indicated that this

was a new type of eukaryotic adenylate

transporter; the transporter was termed

ATP/ADP transport protein (A. thaliana)

[AATP(At)]. AATP(At) has an N-terminal

amino acid extension that is not present

in the bacterial homologues. This extension has a structure typical of four other

proteins that reside in the inner membrane of the plastid envelope, which suggests that AATP(At) is also a plastidic

protein20. As predicted, the gene product of in-vitro-translated AATP cDNA is

incorporated into the inner membrane

of chloroplasts21. Similar cDNAs for plastidic ATP/ADP transporters are present

in maize and potato, and partial sequences from several other plant cDNA

libraries have been identified.

Southern-blot analysis of genomic DNA

extracted from two A. thaliana ecotypes

revealed another isoform of the plastidic

ATP/ADP transporter, AATP2(At) (Ref. 20).

We have cloned and sequenced

AATP2(At), which is very similar to

AATP1(At) (Ref. 22). Sequencing of the

complete genomes of rickettsia and

chlamydia has revealed that there are

four homologues of the tlc gene in rickettsiae and two in chlamydiae. Figure 2

shows the homologies in a selected region of all the currently identified nonmitochondrial ATP/ADP transporters. The

rickettsial and plastidic genes are known

to be expressed, because they were discovered through cDNAs from plastids,

and mRNAs for all five homologous genes

are found in rickettsiae (S. G. E. Andersson

et al., unpublished). However, these

homologues may well exhibit different

biochemical properties and might have

different substrate specificities.

Expression in heterologous systems

A plant transporter, AATP(At), was recently expressed and inserted into the

Escherichia coli cytoplasmic membrane

for the first time23 (in an E. coli strain24

suitable for the heterologous expression

of membrane-bound proteins). The two

heterologously expressed plastidic

ATP/ADP transporters, AATP1(At) and

AATP2(At), mediate the counterexchange

mode of transport and exhibit similar

affinities for ATP and ADP22,23. The difficulty of growing and purifying obligate

intracellular bacteria also makes heterologous expression of their genes in E.

coli highly desirable. We have functionally expressed the rickettsial tlc gene25,26

and both chlamydial genes (H. E. Neuhaus

and H. H. Winkler, unpublished) in

E. coli cytoplasmic membranes. We have

65

REVIEWS

TIBS 24 – FEBRUARY 1999

Figure 2

Similarity of non-mitochondrial adenylate-transport systems and their homologues. The

aligned fragments include the transmembrane helix 4, cytoplasmic loop 5, and part of

transmembrane helix 5 in Rickettsia prowazekii (Rp). Vertical bars indicate residues that

are identical. The bottom three rows indicate residues that are identical in the rickettsial,

chlamydial or plastidic groups. Ct, Chlamydia trachomatis; Ma, maize plastid; Po, potato

plastid; Rr, Rickettsia rickettsii.

also functionally reconstituted both the

plant AATP and the rickettsial tlc gene

products in proteoliposomes.

Regulation and the ATP/ADP transporter

Anabolic metabolism in heterotrophic

plastids depends upon a supply of cytosolic ATP. An analysis of fatty acid and starch

biosynthesis in enriched cauliflowerbud amyloplasts indicated that both

metabolic pathways compete for stromal

ATP27. The rate of end-product synthesis

is dependent on the activity of the ATP/

ADP transporter, is inhibited when other

ATP-consuming reactions are active at

the same time, and does not occur if ATP

is absent from the incubation medium.

The plastidic ATP/ADP transporter has

a high affinity for both ATP and ADP7,22,23;

both metabolites should therefore compete for binding to the transporter in vivo.

Indeed, an increase in the ADP:ATP ratio in

the incubation medium strongly reduces

the rate of starch biosynthesis in isolated

cauliflower-bud amyloplasts8. Hence, the

plastidic ATP/ADP transporter might help

to regulate the rate of end-product synthesis in storage tissues. Moreover, supply of

high levels of carbohydrates to storage

tissues correlates with elevated rates of

respiration and thus a high cytosolic

ATP:ADP ratio28. The increased energy

charge in the cytosol is reflected in the

amyloplast, where it stimulates the incorporation of carbon into starch.

It is generally assumed that the ATP

required for photosynthetic CO2 fixation

derives from the ATP synthase driven by

66

the pH gradient across the thylakoid

membrane. However, there are several

indications that, at least under certain

conditions or in certain types of chloroplast, the uptake of cytosolic ATP supplements anabolic reactions. Such an

ATP uptake would be required when

photosynthesis does not deliver sufficient ATP for CO2 fixation and other anabolic reactions. The plastidic ATP/ADP

transporter should be responsible for

translocating ATP generated in the mitochondria from cytosol to stroma in these

circumstances (see Fig. 3).

Depending on the rate of ATP uptake,

the transport of ATP might contribute

to carbon fixation either by only a few

percent or substantially. Import of ATP

ranges from 5 micromoles per milligram

of chlorophyll per hour (in spinach

chloroplasts)5 to .40 micromoles per

milligram of chlorophyll per hour (in

Digitaria sanguinalis chloroplasts)29.

Finally, in isolated chloroplasts from

sweet-pepper fruits, the addition of ATP

results in the highest observed rates of

starch biosynthesis in the light30. In conclusion, photosynthetic carbon metabolism in several organisms is obviously

positively influenced by exogenous ATP;

the plastidic ATP/ADP transporter is

thus important in both heterotrophic

plastids (i.e. amyloplasts) and photoautotrophic plastids (i.e. chloroplasts).

Transcriptional regulation of the

ATP/ADP transporter is seen in R.

prowazekii31,32. Transcription of mRNA

from the tlc gene is downregulated when

rickettsiae accumulate in large numbers

in the host cell and when rickettsiae are

grown in respiratory-deficient host cells

in low-glucose medium. We suggest that,

as the energy charge in the host cells

falls, fewer ATP/ADP transporters are

synthesized by rickettsiae. Rickettsiae

not only import ATP but also synthesize

ATP by oxidative phosphorylation. In

this sense, they are more like the

photoautotrophic chloroplasts than the

heterotrophic plastids. Thus, if rickettsiae have a higher energy charge than

their, damaged, host cells, there will

be an efflux of ATP from the parasite.

Downregulation of tlc transcription would

therefore be a reasonable way for

rickettsiae to minimize this adverse

exchange of adenylates.

Evolution

Perhaps the most exciting, but speculative, conclusion that can be drawn

from these studies involves the endosymbiotic origins of organelles. According to the endosymbiont hypothesis,

mitochondria evolved from a primitive

eubacterium that exhibited oxidative

metabolism and invaded, and remained

within, a primitive nucleated, nonoxidative cell. This particular symbiotic

relationship gave rise to the modern eukaryotic cell. (See Martin and Müller33

for an alternative view, in which the

host cell was even more primitive.)

What kind of bacterium became a

mitochondrion? Because present-day

mitochondria have retained a small

part of their original bacterial genome,

the sequences and organization of

these retained genes in modern mitochondrial DNA can be compared with a

variety of modern bacteria. Such comparisons suggest that mitochondria

are most closely related to the rickettsial branch of the a division of the

proteobacteria34–38.

We speculate that this obligate-intracytoplasmic precursor of both mitochondria and modern rickettsiae carried out oxidative phosphorylation, was

a dangerous intracytoplasmic parasite

because it could grow faster than its

host cell, and was more useful to its

host than are contemporary rickettsiae.

These rickettsiae could have supplied a

nutrient to the host and/or detoxified

the host’s cytosol by feeding on the

host’s metabolic end products. Although

a non-oxidative host cell would have

been inefficient at converting foodstuffs

to energy, such a cell would still have

had a high energy charge and could

have supplied rickettsiae with ATP.

REVIEWS

TIBS 24 – FEBRUARY 1999

These primitive rickettsiae might have

had an ATP/ADP transporter that preferentially took ATP from the host cytosol,

or a transporter that had no preference

for ADP or ATP. Alternatively, they could

have lacked an ATP/ADP transporter:

the transporter might have appeared

later. However, the lack of an ATP/ADP

transporter must be reconciled with the

observation that chlamydiae, which diverged from the proteobacteria early

on, have a homologous transport system. In any case, we can be sure that the

primitive rickettsia would not have had

a mitochondrial-type transporter that

supplied ATP to the host cytosol.

As protomitochondria evolved from

these rickettsiae, there would have been

a shift from parasitism to symbiosis.

Many genes would have become

nonessential and been lost from, or

modified within, the rickettsial genome.

Rickettsial genes would have been

placed under host-cell control by being

moved to the nucleus, and leader sequences would have evolved in some

products of nuclear genes, both of rickettsial and of non-rickettsial origin, so

that these proteins could be translocated correctly from cytosolic ribosomes to the protomitochondria.

Changes in the rickettsial genome that

made it grow more slowly and less independently could have allowed the modified rickettsiae to remain in the cell

without causing host-cell lysis.

The origin of the nuclear gene that encodes the mitochondrial ADP/ATP transporter is unknown. We can assume that

it did not evolve from a rickettsial transporter, because the two transporters

lack homology. Subsequent evolution of

the animal mitochondrion required only

a massive transfer of genes to the nucleus and a loss of genes that were redundant or useless, such as the rickettsial ATP/ADP transporter. But the

plant cell was just beginning its unique

endosymbiotic relationship39.

Analysis of the residual genome of the

modern chloroplast suggests that

the ancestors of cyanobacteria formed

the primordial chloroplast. Cyanobacteria, if we take Synechocystis sp. as

representative, do not have a homologue of the ATP/ADP transporter. This

is as predicted, because they are not

intracellular bacteria and, thus, no external ATP would be available to them.

However, even without an ATP/ADP

transporter, the eukaryotic cell that

acquired a protochloroplast would

have had a great advantage because it

would have been able to fix CO2.

Oxygen

Water

Light

CO2

ATP

ADP

+

Fuel

Triose phosphate

H

H

+

Metabolites

Mitochondrion

Cytosol

Chloroplast

Figure 3

Flow of ATP (through ATP/ADP transporters) and nutrients between mitochondrion and

cytosol, and between cytosol and chloroplast in a plant cell.

However, as discussed above, if the

only ATP available was derived from

photophosphorylation, such plastids

would have had limited synthetic

ability. The plastid that acquired a

rickettsia-like ATP/ADP transporter

had an advantage.

How do we account for the homology

of the rickettsial and the plastidic transporters? One possible answer is that

the ATP/ADP transporter gene of the

primitive rickettsia was unused and

extraneous in the nucleus of the eukaryotic cell, and was the perfect gene to

be commandeered by the primitive plastid. (Indeed, there are several suggestions that genes that were previously in

the early mitochondrion were transferred to the nucleus and that the gene

products encoded by these genes were

then targeted to plastids39.) Alternatively, the rickettsial gene might by

this time have been lost from the eukaryotic cell, or such a gene might

never have existed in primitive rickettsiae. If so, then there must have been

a second rickettsiae interaction, an

interaction between a more evolved

rickettsiae and a eukaryotic cell that

already had mitochondria, to make this

gene available to the plastid. In either

case, the formerly rickettsial gene

would have been modified to code for a

product that functioned optimally as

a plastidic protein and could be targeted for insertion into the inner membrane of the chloroplast. Such scenarios perhaps explain the curious

fact that, across kingdoms, the plant

and the rickettsial genomes share,

with each other but not with animal

genomes, descendants of a gene that

encodes an ATP/ADP transporter.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Public

Health Service grant AI-15035 from the

National Institute of Allergy and

Infectious Diseases.

References

1 Bruni, A., Contessa, A. R. and Luciani, S.

(1962) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 60, 301–311

2 Vignais, P. V., Vignais, P. M. and Stanislas, E.

(1962) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 60, 284

3 Klingenberg, M. and Pfaff, E. (1966) in

Regulation of Metabolic Processes in

Mitochondria (Vol. 7) (Tager, J. M. et al., eds),

p. 180, Elsevier

4 Klingenberg, M. (1989) Arch. Biochem. Biophys.

270, 1–14

5 Heldt, H. W. (1969) FEBS Lett. 5, 11–14

6 Emes, M. J. and Neuhaus, H. E. (1998) J. Exp.

Bot. 48, 1995–2005

7 Schünemann, D., Borchert, S., Flügge, U. I. and

Heldt, H. W. (1993) Plant Physiol. 103,

131–137

8 Neuhaus, H. E., Henrichs, G. and Scheibe, R.

(1993) Plant Physiol. 101, 573–578

9 Hirschberg, C. B. and Snider, M. D. (1987)

Annu. Rev. Biochem. 56, 63–87

10 Clairmont, C. A., De Maio, A. and Hirschberg,

C. B. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 3983–3990

11 Mayinger, P. and Meyer, D. I. (1993) EMBO J.

12, 659–666

12 Mayinger, P., Bankaitis, V. A. and Meyer, D. I.

(1995) J. Cell Biol. 131, 1377–1386

13 Cleaves, A. E., Novick, P. J. and Bankaitis, V. A.

(1989) J. Cell Biol. 109, 2939–2950

14 Kearns, B. G. et al. (1997) Nature 387,

101–105

15 Winkler, H. H. (1976) J. Biol. Chem. 251,

389–396

16 Hatch, T. P., Al-Hossainy, E. and Silverman, J. A.

(1982) J. Bacteriol. 150, 662–670

17 Klingenberg, M. (1980) J. Membr. Biol. 56,

97–105

18 Williamson, L. R. et al. (1989) Gene 80,

269–278

19 Plano, G. V. and Winkler, H. H. (1991)

J. Bacteriol. 173, 3389–3396

20 Kampfenkel, K. et al. (1995) FEBS Lett. 374,

351–355

21 Neuhaus, H. E. et al. (1997) Plant J. 11, 73–82

22 Möhlmann, T. et al. (1998) Eur. J. Biochem.

252, 353–359

23 Tjaden, J., Schwöppe, C., Möhlmann, T. and

67

REVIEWS

TIBS 24 – FEBRUARY 1999

Neuhaus, H. E. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273,

9630–9636

Miroux, B. and Walker, J. E. (1996) J. Mol. Biol.

260, 289–298

Krause, D. C., Winkler, H. H. and Wood, D. O.

(1985) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 82,

3015–3019

Dunbar, S. A. and Winkler, H. H. (1997)

Microbiology 143, 3661–3669

Möhlmann, T., Scheibe, R. and Neuhaus, H. E.

(1994) Planta 194, 492–497

Hatzfeld, W-D., Dancer, J. and Stitt, M. (1990)

24

25

26

27

28

Planta 180, 205–211

29 Huber, S. C. and Edwards, G. E. (1976)

Biochim. Biophys. Acta 440, 675–687

30 Batz, O., Scheibe, R. and Neuhaus, H. E. (1995)

Planta 196, 50–57

31 Cai, J. and Winkler, H. H. (1996) J. Bacteriol.

178, 5543–5545

32 Cai, J. and Winkler, H. H. (1997) Acta Virol. 41,

285–288

33 Martin, W. and Müller, M. (1998) Nature 392,

37–41

34 Gupta, R. S. (1995) Mol. Microbiol. 15, 1–11

Oncogenic alterations of

metabolism

Chi V. Dang and Gregg L. Semenza

Over seven decades ago, classical biochemical studies showed that

tumors have altered metabolic profiles and display high rates of glucose

uptake and glycolysis. Although these metabolic changes are not the

fundamental defects that cause cancer, they might confer a common advantage on many different types of cancers, which allows the cells to survive and invade. Recent molecular studies have revealed that several of

the multiple genetic alterations that cause tumor development directly

affect glycolysis, the cellular response to hypoxia and the ability of tumor

cells to recruit new blood vessels.

A GENETICALLY ALTERED neoplastic

cell has special metabolic requirements

for its development into a three-dimensional tumor mass. Monolayer cultures

do not reflect the three-dimensional cellular growth of an avascular tumor,

which can be mimicked in soft-agar

anchorage-independent-growth assays.

When a tumor has grown to a detectable size, the local environment of

the cancer cells often becomes heterogeneous1. Small (,1 mm diameter)

tumor nodules, as well as microregions

of larger tumors, often have microecological niches that display significant

gradients of critical metabolites such as

oxygen, glucose and other nutrients

or growth factors (Fig. 1a). Tumors, in

contrast to normal tissue, exist in acidic

environments that result from production

C. V. Dang is at the Depts of Medicine,

Oncology, Pathology, and Molecular Biology

and Genetics, Johns Hopkins University

School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21205,

USA; and G. L. Semenza is at the Depts of

Pediatrics and Medicine, and the Institute of

Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University

School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21205,

USA.

Email: cvdang@welchlink.welch.jhu.edu

68

of lactate and other acids. The cytosolic

pH of tumor cells, however, is maintained

as it is in normal cells.

Hypoxia occurs in tumor tissue that

is .100–200 mm away from a functional

blood supply2. Thus, tumor survival depends, in part, on the ability to recruit

new blood microvessels through angiogenic factors (Fig. 1b). Hypoxia tends to

be widespread in solid tumors, however, because cancer cells are more prolific than the invading, recruited endothelial cells, which commonly form a

new, disorganized blood supply. Human

tumors endure profound hypoxia,

which indicates that adaptation to hypoxic conditions is a crucial step in

tumor progression. The anaerobic use

of glucose as an energy source through

glycolysis (Fig. 2a) is, therefore, a

feature common to most solid tumors.

A better understanding of cancers at

the molecular level has provided insights into the causes of altered

metabolism in oncogenesis. Various

metabolic changes have been observed

in tumors. Here, however, we emphasize

changes in glucose metabolism and cellular responses to hypoxia, and discuss

three specific areas: (1) physiological

35 Gray, M. W. (1995) in Molecular Biology of Plant

Mitochondria (Sevings, C. S., III and Vasil, I. K.,

eds), pp. 635–659, Kluwer Academic Publishers

BV

36 Olsen, G. J., Woese, C. R. and Overbeek, R.

(1994) J. Bacteriol. 176, 1–6

37 Viale, A. and Arakaki, A. K. (1994) FEBS Lett.

341, 146–151

38 Andersson, S. G. E. et al. (1998) Nature 396,

133–143

39 Martin, W. and Schnarrenberger, C. (1997)

Curr. Genet. 32, 1–18

responses used by tumor cells to adapt

to hypoxia; (2) oncogenic changes that

affect glucose metabolism; and (3)

tumor metabolism and apoptosis.

Hypoxia in tumors and normal tissues:

activation of genes that encode glycolytic

enzymes and vascular endothelial growth

factor

Normal tissue displays an oxygen

gradient across a distance of 400 mm

from a blood supply. By contrast, in situ

measurements of oxygen tension in

human tumors and tumor xenografts revealed significant hypoxia: cells adjacent to capillaries displayed a mean

oxygen concentration of 2%, and cells

located 200 mm from the nearest capillary displayed a mean oxygen concentration of 0.2% (Ref. 2). The profoundly

hostile environment selects for cells

that are adapted to chronic hypoxia. In

normal cells, a critical response to hypoxia is the induction of the hypoxiainducible transcription factor HIF-1, a

basic–helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor that consists of two

subunits, HIF-1a and HIF-1b (Ref. 3).

HIF-1b is also known as the arylhydrocarbon-receptor nuclear translocator

(ARNT)3. HIF-1 binds to the DNA sequence 59-RCGTG-39 and increases the

expression of genes that encode glycolytic enzymes, including aldolase A,

enolase 1, lactate dehydrogenase A

(Fig. 2b), phosphofructokinase L, phosphoglycerate kinase 1 and pyruvate

kinase M, as well as the vascular

endothelial growth factor (VEGF) gene,

which is important for angiogenesis4–8

(Fig. 3). In addition to alterations in oxygen tension, changes in glucose concentration also activate many glycolytic

enzyme genes through the carbohydrate-response element (ChoRE; 59CACGTG-39), which matches the consensus binding-site sequences for MYC

and HIF-1 (Fig. 2b)9,10. Studies of knockout mice have implicated HIF-1 and the

HLH–leucine-zipper transcription factor

USF2, which also binds to the 59CACGTG-39 sequence, in the regulation

0968 – 0004/99/$ – See front matter © 1999, Elsevier Science. All rights reserved.

PII: S0968-0004(98)01344-9