A New Approach to Limitations of Remedies and Damages Under the

advertisement

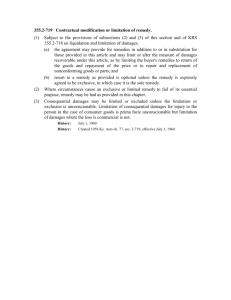

A New Approach to Limitations of Remedies and Damages Under the UCC By Peter C. John This article reviews the Illinois Supreme Court’s decision in Razor v Hyundai Motor America, which changed existing Illinois law by limiting the failure of a remedy to the remedy rather than also implicating the limitation on damages. M ost commercial contracts for the sale of goods entered into between businesses contain some form of limitation of remedy and/or limitation of damages. Although these concepts are often grouped together, they are essentially separate, with separate limitations and separate defenses. It is important for lawyers to understand this distinction, because for 36 years Illinois courts ignored it and held that if a limited remedy fails of its essential purpose, the limitation of damages also fails. The law in Illinois has now dramatically changed. This article explains the practical differences between limitation of remedy and limitation of damage clauses and analyzes the prior failure to recognize the logical distinction between both clauses. It then looks at the Illinois Supreme Court’s 2006 decision in Razor v Hyundai Motor America,1 which changed existing Illinois law by limiting the failure of a remedy to the remedy rather than also implicating the limitation on damages. It is important for practitioners to understand the basis for this change, which should significantly influence litigation strategy and results in disputed commercial transactions. __________ 1. 222 Ill 2d 75, 854 NE2d 607 (2006). ______________________________________________________________________________________ Peter C. John <pcj@willmont.com>, of Williams, Montgomery & John in Chicago, is a commercial trial lawyer with almost forty years of experience, and served for nine years on the Illinois Supreme Court Civil Jury Instruction Committee. Hong Lee, an associate, provided research support. 1 Background The main source for contractual limitations under Illinois law is the statutory Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) section 2-103 et seq, which applies to the sale of goods only.2 In contract actions controlled by the UCC, the relevant remedy provisions are listed in section 2-703 (Seller’s Remedies in General) and section 2-711 (Buyer’s Remedies in General). Both sections include non-damage remedies such as withholding delivery of goods by the seller (section 2-703(a)) or buyer’s rightful rejection (section 2711(1)) or specific performance (section 2-711(2)(b)). The remedies sections also list many types of traditional damage claims, e.g., claims for money (sections 2-703(d and e), 2-711(1)(a and b)). Thus, the UCC includes traditional damage claims as remedies. We point this out since it becomes relevant when we evaluate the UCC limitations, which treat remedy and damage limitations separately. The UCC provision concerning limitation of remedy and damages is UCC section 2-719, which provides as follows: 2-719. Contractual modification or limitation of remedy. (1)Subject to the provisions of subsections (2) and (3) of this Section and of the preceding section on liquidation and limitation of damages, (a) the agreement may provide for remedies in addition to or in substitution for those provided in this Article and may limit or alter the measure of damages recoverable under this Article, as by limiting the buyer’s remedies to return of the goods and repayment of the price or to repair and replacement of non-conforming goods or parts; and (b) resort to a remedy as provided is optional unless the remedy is expressly agreed to be exclusive, in which case it is the sole remedy. (2)Where circumstances cause an exclusive or limited remedy to fail of its essential purpose, remedy may be had as provided in this Act. (3)Consequential damages may be limited or excluded unless the limitation or exclusion is unconscionable. Limitation of consequential damages for injury to the person in the case of consumer goods is prima facie unconscionable but limitation of damages where the loss is commercial is not. The interaction between sections 2719(2) and (3) with respect to limita- tions of both remedies and damages is the subject of the Illinois Supreme Court’s decision in Razor. Illinois law prior to Razor automatically fails with the remedies limitations clause.5 In J. I. Case, the court held that the defendant’s failure to fix a broken tractor pursuant to a limited warranty of repair rendered that limitation – including its restriction on consequential damages under section 2-719(3) – unenforceable: Until the Illinois Supreme Court decision in Razor, the lower Illinois state courts that had taken up this issue did Had [the defendants] reasonably comnot interpret sections 2-719(2) and 2plied with their agreement contained in 719(3) separately with respect to the the warranty they would be in a position defense to each limitation, even though to claim the benefits of their stated limeach defense is recognized as a separate ited liability and to restrict plaintiff to his test measured at different time periods. stated remedy. The limitations of remedy The section 2-719(2) test is the failure and of liability are not separable from of essential purpose of the remedy at the the obligations of the warranty. Repudiation of the obligations of the warranty time of performance, while the section destroy[s] its benefits.6 2-719-(3) test is unconscionability at the time of contracting. In the past, Illinois UCC jurisprudence has held that if a remedy fails of its It is important for practitioners essential purpose under section 2-719(2), the limito review Razor, which should tation of damages under significantly influence litigation section 2-719(3) also fails on a benefit of the barstrategy and results in disputed gain theory.3 Accordingly, commercial transactions. Illinois courts treated limitation of damage clauses under section 2-719(3) as being dependent on the limitation of remedies Nowhere did the court discuss unclauses under section 2-719(2). conscionability at the time of contractFor instance, consider the case where there is a contract for the sale of goods in ing. The court specifically acknowledged Illinois. This contract contains a remedy that plaintiff did not plead coercive, limitation clause that provides that the fraudulent, or unconscionable sales tac7 exclusive remedy for a breach in the sale tics. The court only relied on section 2of goods is repair or replacement under 719(2), which states that where an exsection 2-719(2). The contract also con- clusive or limited remedy fails of its estains a clause providing that consequen- sential purpose, remedy may be had as 8 tial damages are unavailable pursuant to provided by the UCC. One of the remedies available under section 2-719(3). Suppose in this instance that a party the UCC is the limitation of consequenrepudiates its repair obligations under a __________ 2. 810 ILCS 5/2-103. If the contract involves limited remedy clause, thereby causing services, it is not controlled by the UCC, but by Illinois the remedy to fail in its essential purpose. common law. There are no Illinois cases of which the Under the reading of section 2-719 set author is aware which have adopted the UCC principles limitations for services unless the contract forth in Adams v J. I. Case Co,4 the seller concerning is predominantly for the sale of goods. See Belleville may not enforce the benefits of the lim- Toyota, Inc v Toyota Motor Sales, USA, Inc, 199 Ill 2d 325, 352, 770 NE2d 177, 194-95 (2002); And ited remedy under section 2-719(2). Zielinski v Miller, 277 Ill App 3d 735, 741, 660 NE2d In addition, the seller will also lose 1289, 1294 (3d D 1995). 3. Adams v J. I. Case Co, 125 Ill App 2d 388, any purported limitation on consequen261 NE2d 1, 7-8 (4th D 1970) (“It should tial damages under section 2-719(3) re- 402-03, be obvious that they cannot at once repudiate their gardless of whether the section 2-719(3) obligation under their warranty and assert its provisions remedy was unconscionable at the time beneficial to them.”); see also Lara v Hyundai Motor 331 Ill App 3d 53, 63, 770 NE2d 721, 729 of contracting. Even though the buyer America, (2d D 2002). would still have the remedy of direct 4. J. I. Case (cited in note 3). 5. Id at 402-03, 261 NE2d at 8. damages if consequential damages re6. Id at 402, 261 NE2d at 7. mained barred, Illinois courts have held 7. Id. 8. Id at 403, 261 NE2d at 8. that the limit on consequential damages 2 tial damages. The court’s evaluation may well have assumed that the provision that remedy may be had as provided by the UCC trumps the section 2-719(3) limitation.9 Earlier Illinois cases followed the analysis of J. I. Case. In Lara v Hyundai Motor America, the court held that an issue of fact existed as to whether the limited remedy of repair and replacement was met.10 However, without any analysis the Lara court stated that If the finder of fact concludes that the limited remedy of replacement or repair of defective parts failed of its essential purpose, the express warranty’s exclusion of consequential and incidental damages will have no effect and those damages will be available to plaintiff pursuant to the UCC.11 These cases culminated in the Illinois First District Appellate Court’s decision in Razor. There, the court again held without analysis that [W]here a contract limits a remedy to repair and/or replacement of defective parts or goods and the remedy failed in its essential purpose, a provision excluding incidental and consequential damages will have no effect and those damages will be available to the plaintiff pursuant to the UCC.12 The Razor decision The Razor case was appealed to the Illinois Supreme Court, which performed a thorough analysis of the issue and abrogated J. I. Case and Lara. In Razor, the Illinois Supreme Court confronted the holding in J. I. Case over the enforceability of a consequential damages disclaimer in a limited warranty. The plaintiff in Razor purchased a new car from the defendant that eventually broke down soon after purchase. The plaintiff initiated an action against the defendant for breach of written warranty and of implied warranty of merchantability under the Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act. He prevailed in arbitration, trial, and again on appeal. Before the Illinois Supreme Court, the defendant argued that the lower courts had improperly invalidated the warranty’s limitation on consequential/ incidental damages when they held that the car’s warranty failed of its essential purpose under UCC section 2-719(2). The defendant did not contest the finding that its warranty had failed of its essential purpose.13 Rather, it argued that the lower courts improperly disregarded ing the buyer’s remedies to return of the the car warranty’s limitation on congoods and repayment of the price or to sequential/incidental damages without repair and replacement of non-conformmaking a separate finding that the limiing goods or parts. tation was unconscionable under section And UCC section 2-719(2) provides 2-719(3). thusly: In considering this issue, the Illinois (2) Where circumstances cause an exSupreme Court noted the existence of clusive or limited remedy to fail of its esthree different schools of thought: (i) the sential purpose, remedy may be had as “dependent approach” used in J. I. Case provided in this Act. Co, where the enforceability of a consequential damages exclusion was continThe Razor court held that gent on the survival of a limitation of remedy; (ii) the the existence of two different “independent approach,” standards in the UCC for where the enforceability of a consequential damages evaluating limitations on exclusion depended upon remedies and consequential a finding that the exclusion is not unconscionable, damages supported treating regardless of whether any them differently. limitation of remedy survived; and (iii) the “case by case” approach. After analyzing the benefits and drawbacks of these three apUCC section 2-719(3) provides as folproaches, the Illinois Supreme Court lows: opted to follow the majority of other (3) Consequential damages may be jurisdictions in adopting the independent limited or excluded unless the limitation or exclusion is unconscionable. Limitation approach.14 The court noted that nothing of consequential damages for injury to the in the text or comments to section 2-719 15 person in the case of consumer goods is supported the dependent approach. prima facie unconscionable but limitaRather, the court held, the existence of tion of damages where the loss is comtwo different standards in the UCC for mercial is not. evaluating limitations on remedies and Notice that the drafters of section 2consequential damages (failure of es719 appear to separate remedies from sential purpose and unconscionability, damages in (1)(a) by allowing the parties respectively) supported the independent to “limit or alter the measure of dam16 approach. ages recoverable under this Article, as by The court also found that the depen- limiting the buyer’s remedies to return of dent approach’s automatic elimination __________ of limitations on consequential damages 9. See also Jones & McKnight Corp v Birdsboro without considering the good/bad faith Corp, 320 F Supp 39, 43-44 (ND Ill 1970) (applying of the seller went beyond the contempla- Pennsylvania law) (holding that failure to repair under exclusive remedy provisions of section 2-719(2) would tion of the UCC,17 and that adopting the vitiate the purported limitation on damages under more common independent approach section 2-719(3) and permit recovery of consequential again without mention of unconscionability promoted the UCC’s goals of unifor- damages under section 2-719(3)); Dynamic Recycling v Shred 18 mity. Pax Corp, 210 Ill App 3d 602, 614-15, 569 NE2d The Illinois Supreme Court’s decision 570, 577-578 (2d D 1991) (holding that defendant’s failure to remedy defects in tire shredder precluded in Razor is consistent with a reasonable enforcement of limitation on damage provision under section 2-719(3)). interpretation of UCC section 2-719. 10.Lara at 63, 770 NE2d at 729. Again, section 2-719 (1)(a) provides as 11.Id, citing 810 ILCS 5/2-719(2). follows: 12.Razor v Hyundai, 349 Ill App 3d 651, 667, 813 (1) Subject to the provisions of subsections (2) and (3) of this Section and of the preceding section on liquidation and limitation of damages, (a) the agreement may provide for remedies in addition to or in substitution for those provided in this Article and may limit or alter the measure of damages recoverable under this Article, as by limit3 NE2d 247, 262 (1st D 2004), citing Lara at 63, 770 NE2d at 729. 13.Razor (SC) at 87, 854 NE2d at 615. 14.Id at 98-99, 854 NE2d at 622. 15.Id at 92, 854 NE2d at 618. 16.Id at 92-93, 854 NE2d at 618-19. 17.Id at 94-95, 854 NE2d at 619-20. 18.Id at 99, 854 NE2d at 622. Lack of uniformity and predictability, in turn, is what motivated the court to reject the “case by case” approach. Id at 90-91, 854 NE2d at 617-18. the goods and repayment of the price or to repair and replacement of non-conforming goods or parts.” (Emphasis supplied.) These limited remedies do not include damages. Thus, under section 2-719(1)(a) the parties can agree to limit the remedies to non-damage remedies only. Therefore, the issue of limited remedy is dealt with separately only in section 2-719(2) whereas section 2-719(3) only deals with a limitation of damages. This distinction continues in section 2-719(2) and (3), which provide defenses to limitations of remedies and damages. Section 2-719(2) provides that when a limited remedy fails of its essential purpose, then the limited remedy ends. Section 2-719(3), on the other hand, deals only with a damage issue – special, incidental and consequential damages – stating that if a limitation of consequential damages is unconscionable, it fails. Thus, the different treatment of defenses in section 2-719(2) and section 2-719(3) strongly suggests that each section should be analyzed independently. There is no express provision in section 2-719, or anywhere else in the UCC which provides the limitation of consequential damages ends due to the failure of its essential purpose of a limited remedy under section 2-719(2). Only a limited remedy under section 2-719(2) can fail of its essential purpose under the UCC. If, for example, the contract contains a limited “repair or replacement” remedy, but the seller has failed to perform its repair obligations during the warranty period, a jury would be justified in finding that the repair or replacement remedy failed of its essential purpose.19 Accordingly, the failure of essential purpose analyzes the performance of the limited remedy. Unconscionability of the damage limi­ tation, on the other hand, is evaluated from the perspective of the parties’ rela­ tive bargaining position at the time of contract formation.20 Illinois specifically recognizes the defense of unconscionability in a breach of contract action.21 Unconscionability can be found on either procedural or substantive grounds, or a combination of both.22 “Procedural unconscionability consists of some impropriety during the process of forming the contract depriving a party of a meaningful choice.”23 Substantive unconscionability, on the other hand, “concerns the actual terms of the contract and examines the relative fairness of the obligations assumed.”24 Based on evidence adduced at trial in Razor that the warranty and consequential/ incidental damages exclusion were not shown to the plaintiff at the time of sale, the Illinois Supreme Court made the independent determination that exclusion was procedurally unconscionable under section 2-719(3) and refused to apply the exclusion against the plaintiff.25 It is also clear that the analysis for evaluating defenses to section 2-719(2) limitation of remedy provisions and section 2-719(3) limitation of consequential damages are completely different. The relevant time for analyzing each defense is different as well. A limited remedy is allowed unless it fails of its essential purpose, which is to provide the limited remedy the buyer agreed to accept in the commercial negotiations. The failure is judged during the performance of the limited remedy by the seller and still leaves the buyer able to recover based on other remedies, including direct damages. By way of contrast, the test for unconscionability focuses on the formation of the contract based on the requirement of procedural unconscionability. Its purpose is to prevent a seller from taking advantage of the buyer in the negotiation pre-contract process. In short, a close inspection of the construction of section 2-719(2) and 2719(3) remedy and damage limitations finds that they were intended to be evalu­ ated separately as the Illinois Supreme Court has now held in Razor since each is a different concept, and each is judged by different standards both in the elements to determine failure and the time period to judge failure. Federal courts started the change in result Several federal courts in Illinois had previously rejected the J. I. Case analysis of sections 2-719(2) & (3) under Illinois law. Each court treated sections 2-719(2) remedies limitation provisions and section 2-719(3) consequential damage limitation provisions separately.26 In AES Technology Systems, Inc v Coherent Radiation, the seventh circuit said, “[W]e reject the contention that failure of the essential purpose of 4 the limited remedy automatically means that a damage award will include consequential damages.”27 Rather, the AES court requires an analysis of whether a section 2-719(3) consequential damages clause is unconscionable before allowing consequential damages. In ruling that sections 2-719(2) and (3) should be analyzed independently, the AES court emphasized that “[t]he purpose of the courts in contractual disputes is not to re-write contracts by ignoring parties’ intent; rather, it is to interpret the existing contract as fairly as possible when all events did not occur as planned.”28 Other jurisdictions have also recognized this distinction between the defense to a remedy limitation in section 2-719(2) and a damage limitation in section 2-719(3). For example, the U.S. District Court for the District of Connecticut in McKernan v United Technologies Corp, Sikorsky Aircraft Division,29 concluded that the Connecticut Supreme Court would hold that the UCC subsection authorizing the exclusion of consequential damages – section 2-719(3) – is independent from the limited remedy provision, section 2-719(2), and fails only if unconscionable, not when the limited remedy __________ 19.See J. I. Case at 402, 261 NE2d at 7. 20.810 ILCS 5/2-302. 21.See Kinkel v Cingular Wireless LLC, 223 Ill 2d 1, 20, 857 NE2d 250, 263 (2006). 22.Razor (SC) at 99, 854 NE2d at 622; but see Zobrist v Verizon Wireless, 354 Ill App 3d 1139, 1148, 822 NE2d 531, 541 (5th D 2004) (“‘“The more substantively oppressive the contract, the less evidence of procedural unconscionability is required to come to the conclusion that the term is unconscionable, and vice versa.”’”) Id, quoting Ting v AT&T, 319 F3d 1126, 1148 (quoting Armendariz v Foundation Health Psychcare Services, Inc, 24 Cal 4th 83, 114, 6 P3d 669, 690 (2000)). 23.Kinkel at 23, 857 NE2d at 264, quoting Frank’s Maintenance & Engineering, Inc v C. A. Roberts Co, 86 Ill App 3d 980, 989-90, 408 NE2d 403, 410 (1st D 1980). 24.Kinkel at 28, 857 NE2d at 267, quoting Maxwell v Fidelity Financial Services, Inc, 184 Ariz 82, 89, 907 P2d 51, 58 (1995). 25.Razor (SC) at 101, 854 NE2d at 623. The dissent supported the majority’s adoption of the independent approach. Id at 111, 854 NE2d at 629 (McMorrow dissenting). However, the dissent took issue with the majority’s holding on unconscionability on the grounds that the majority opinion imposed upon manufacturers an unreasonable requirement to ensure the presentation of warranties at the time of sale, and would thereby discourage manufacturers from offering warranties on their products. Id at 119, 854 NE2d at 633. 26.AES Technology Systems, Inc v Coherent Radiation, 583 F2d 933, 941 (7th Cir 1988). 27.Id. 28.Id. See also, Smith v Navistar Intl Trans Corp, 957 F2d 1439, 1443 (7th Cir 1992); Lefebvre Intergraphics, Inc v Sauden Machine Ltd, 946 F Supp 1358, 1370-71 (ND Ill 1996). 29.717 F Supp 60 (D Conn 1989). fails in section 2-719(2).30 The court also recognized that the UCC “tests each by a different standard” and there are “two discrete ways of attempting to limit recovery for breach of warranty.”31 Even back in 1989, when McKernan was decided, this treatment of the two subsections as independent was described as “the current trend” and the “better reasoned approach.”32 The Indiana Supreme Court in Rheem Mfg Co v Phelps Heating & Air Conditioning, Inc,33 held the exclusion of consequential damages under section 2719(3) fails only if unconscionable at the time of contract and is therefore independent of the failure of essential purpose of the limited remedy under section 2-719(2).34 The court provided four sound reasons why that result is dictated by the UCC: 1. The drafters of the UCC inserted distinct legal standards differentiating section 2-719(2) from section 2-719(3), and there are also distinctions in who applies the standards – section 2-719(2) a jury, whereas section 2-719(3) the court. 2. The independent view is consistent with statutory interpretation to give full effect to each of the terms. A dependent view would read section 2-719(3) as unnecessary when there is a failure of essential purpose. 3. The independent view supplies simplicity and clarity by allowing a clearly expressed agreement to control a transaction, and allows the parties to anticipate the results. 4. The independent view allows the parties freedom of contract, a goal of the UCC.35 Conclusion In Razor, the Illinois Supreme Court finally conducted its own evaluation of this significant commercial issue rather than reciting prior Illinois boilerplate from the J. I. Case decision. It thus joined the majority of jurisdictions and followed the more logical path. ■ __________ 30.Id at 72. 31.Id at 70, quoting Chatlos Systems, Inc v NCR Corp, 635 F2d 1081, 1086 (3d Cir 1980). 32.McKernan, 717 F Supp at 70. 33.746 NE2d 941 (Ind Sup Ct 2001). 34.Id at 947-48. 35.Id at 948-51. Reprinted from the Illinois Bar Journal, Vol. 96 #2, February 2008. Copyright by the Illinois State Bar Association. www.isba.org 5