Don`t Tase Me Bro: A Lack of Jurisdictional Consensus Across

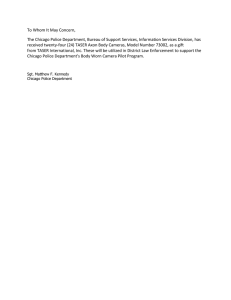

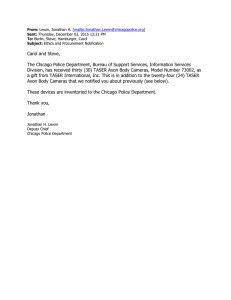

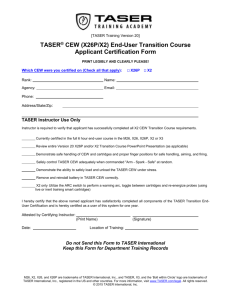

advertisement