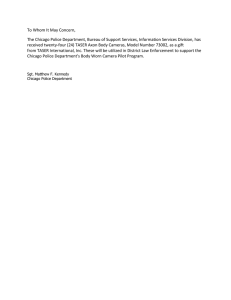

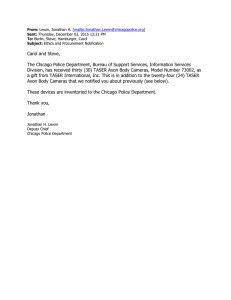

Shocking the Conscience: What Police Tasers and Weapon

advertisement