Mini-Module: Breadboard Prototyping System

advertisement

Mini-Module: Breadboard Prototyping System

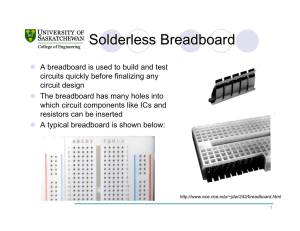

The breadboard prototyping system that we use to put circuits together in this class makes your

life a lot easier IF it is used properly. We will come to rely on some simple relationships

between the holes on the breadboard (BB) which will not be true if you or someone else had

inserted a device with too large pins into the breadboard. When in doubt, don’t do it! Look at

the wires on the little ¼ W resistors; if your wire is bigger than that, it shouldn’t go in the

breadboard. If you have a component that looks too big, either come and ask the instructor what

to do, or use the breadboarding pins as I will show you.

{getting off my soapbox now…}

Connections

The breadboard makes circuit connections easy by using pre-established connections within the

board along rows and columns and by making connection to the external devices as easy as

inserting them in the little holes. If you could look down inside the little hole, you would see

little springy connections that are pushed aside when a wire is inserted. These are the source of

the connection between the breadboard and the external device. This is also a possible source of

problems, since too big of a wire will either deform the little springy things, so the y never make

connection again (which is bad) OR push the little springy things into their neighbor (which is

worse, since you now have an unexpected, often unpredictable connection that wasn’t there

before.) Most devices can be inserted virtually anywhere in the board as needed, but DIP (dual

inline package) type chips are usually inserted across one of the little trenches in the board.

You’ll see that the chips and breadboard are both designed to make this really easy. The logic of

having this setup will become more apparent when we talk about the layout of the breadboard

below and even more apparent when we start to work with these chips. One little saying that I

inherited from the electronics engineer at the University of Arizona (a heck of a nice guy) that

you will hear me say a lot in this class is “95% of the time, the problem is connections.” We

hope to keep those types of problems down a bit using the breadboards properly, but you will be

amazed how often this saying is right.

Board Layout

The connectivity of the rows and columns of holes in the breadboard is designed to help make

circuit construction easier. First, the columns of holes emanating out from the center trenches

are all hooked together. This is the primary mechanism for connecting circuit elements together.

Want to join two resistors? Put one end of each in two holes in the same column (on the same

side of the trench.) In order to make power and ground available all over the board, the bottom

and top of each set of trenches is a row of two holes, called a bus. The connectivity in this case

is along the row. (Be careful, sometimes you have to join parts of the strip together – look for a

break in the middle. You can always check with your DMM if you aren’t sure.) Generally you

will connect the power supplies and ground to the ends of these bus strips and then bring power

into the various devices and entry points of your circuit using little jumper wires connected to the

nearest hole on the bus. This helps to minimize the total number of connections that need to be

made between devices. (Two things that are connected together on a schematic and then

connected to ground need not really be connected together. It would suffice to just connect each

to ground.)

Tips

Think before you set up a circuit. Where should you put the major elements? Where will the tie

points be? Will an element need a potentiometer for some adjustment? It will make more sense

to put the pot closer than farther away. Don’t use great big loops of wire if you can help it, they

fall out easily and are antennas for high frequency noise. Use the different lengths (and colors)

of wire to your advantage. Low and tight is best, wherever possible.