Methods of Writing Instruction

Chapter Seven

I. The Basic Building Blocks of Writing

II. Instructional Contexts Along a Continuum of Teacher Directedness

III. The Writing Process: Pre-Writing, Drafting, Revising, Editing, and Publishing

Although we have artificially separated reading and writing instruction to clearly explain them both, we

must start this chapter by reiterating that reading and writing are inextricably intertwined skills and

processes. We cannot and should not separate the teaching of reading from the teaching of writing. As

you will see, the component skills of reading and writing are most effectively taught in connection with

one other. In fact, students achieve the greatest academic gains when their teachers effectively harness

the synergy of the reading-writing partnership. As Marilyn Jager Adams notes, “Children’s achievements

in reading and writing are quite strongly and positively related… an emphasis on writing activities results

in gains in reading achievement.”161

Chapter Overview

We will approach the subject of writing instruction from three, overlapping angles:

Part I—The Basic Building Blocks of Writing

First, we will examine the basic building blocks of writing, such as spelling, grammar, and handwriting.

Students become effective writers more quickly when we teach these fundamental mechanics explicitly

and then ask students to put the building blocks into practice by writing with varying levels of teacher

support.

Part II—Instructional Contexts Along a Continuum of Teacher Directedness

In Part II, we will explore a series of the most effective instructional contexts for writing that fall along a

broad continuum of teacher-directedness. As you recall, a fundamental tenet of excellent literacy

instruction is that the teacher leads students toward independence as active readers and writers by

providing increasingly less guidance and support over time. While most of us will teach in ways that fall

on several places on this continuum on any given day, as a general matter, successful teachers of writing

are those that lead their students toward self-reliance in the writing process. To that end, we will survey

five contexts in which to teach writing—Modeled Writing, Shared Writing, Interactive Writing, Guided

Writing, and Independent Writing—each method more student-driven than the last.

Part III—The Writing Process: Pre-Writing, Drafting, Revising, Editing, and Publishing

In order for students to write independently, they need to know and be able to use the five-step writing

process: pre-writing, drafting, revising, editing, and publishing. In Part III of this chapter, we will consider

the writing process itself, looking closely at techniques teachers use to teach the its five steps. Of course,

this framework is not meant to be an alternative to (and is not in tension with) the various methods

discussed in Part II. In fact, all of the stages of the writing process can be taught through Modeled,

Shared, Interactive, Guided, and Independent Writing.

Adams, Marilyn Jager. Beginning to Read: Thinking and Learning about Print. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990, p.

375.

161

125

Methods of Writing Instruction

I. The Basic Building Blocks of Writing

Reading and writing are complex, interrelated processes. To read, we break apart a string of letters,

decide which sounds those letters represent, and put the sounds back together to determine the word. To

spell, we translate the sounds that we hear in speech into written letters. In this way, reading and

spelling are opposite but related activities. For this reason, much of the information gleaned in Chapter

Three, “The Building Blocks of Literacy,” will be useful as you guide your students toward writing

proficiency. In this section, we will consider some guidelines for teaching spelling, grammar, and

handwriting.

Invented and Conventional Spelling

Children proceed through a relatively predictable set of sequential stages in learning to write. They first

scribble, and then make linear, repetitive drawings that might resemble cursive in English. Children in

this emergent stage may use a few very familiar letters, primarily those contained in their names, to spell

all words (you might be surprised that four-year old Dominic would

write MDNC for float). Next, children begin to write letters that

Spelling and Handwriting?

represent beginning and ending sounds in words (writing ft for

“Adults may wince at painful

float), and progress to include some consonant blends and vowels childhood memories of penmanship

(flot for float). As they understand more of the patterns that

lessons and spelling tests. A small

influence spelling, children will be able to spell most single syllable but growing number of studies,

words with phonetic accuracy (flote for float) but will have difficulty

though, suggest that systematically

teaching handwriting and spelling

spelling across syllables (confedent for confident). In the final

might actually help some students

stage, children are able to spell most words correctly, though they

write more and do it better.”162

may make small errors in the spelling of words containing silent

letters or those derived from other languages (inditement for

indictment).163

As children are motivated to write, their interest in communicating inevitably outpaces their knowledge of

proper spelling. If we accept that students’ interest in communicating should take precedence over

correct spelling, we are able to ensure that students’ interest in communicating does not outpace their

ability to write. We simply have to allow young children to “write” in less conventional ways.

Kindergarten through second grade teachers in particular should keep in mind that “invented spelling” is

a critical part of the literacy developmental process. Children who are using invented spelling are

demonstrating that they are concentrating on the sound/symbol relationship and then trying to encode it

themselves. At first this process doesn’t reflect all the patterns that apply to a language (mostly because

the student simply hasn’t learned them all yet), so a teacher may see many words that are conventionally

misspelled, but still reflect a growing knowledge of the sound/symbol relationship.

chrane train

dwg dog

fesh fish

n and

There is some controversy about when the transition from invented to conventional spelling should occur.

Different students will reach the stage where they are consistently using conventional spelling at

different times. Usually by upper elementary, students should not be encouraged to use invented

spelling, but rather to use resources to find the correct or standard spelling of words.

Viadero, Debra. “Studies Back Lessons in Writing, Spelling.” Educational Leadership, November 20, 2002.

Bear, Donald R. et al. Words Their Way: Words Study for Phonics, Vocabulary, and Spelling Instruction, 3rd Edition.

New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2004, pp. 11-20.

162

163

126

The bottom line is that invented spelling should be

encouraged when it signals that students are using their

knowledge of sound-symbol correspondences to reach

beyond the spelling patterns they have been taught. We

do not want inability to spell a word to stop students from

writing. However, conventional spelling is the ultimate

goal, and students should be held responsible for spelling

words and word patterns that they have been taught.

No matter what grade, no matter what level, kids

will ask you how to spell whichever word they

want to use. Teach them spelling strategies

(including to just sound it out if they don’t have

any clue), and then let them make mistakes. If

you don’t, they’ll never become independent

writers. Then you can use those mistakes that

they make to guide your instruction to spelling

objectives that they need help with.

Guidelines for Teaching Spelling

All students benefit from systematic spelling instruction

Shannon Dingle, RGV ‘03

and practice, and students who are experiencing difficulty

in spelling need intensive instruction and practice tailored to match their individual levels of word knowledge.

Strategically select spelling words. Depending on your school’s curriculum, you may be handed lists of

words that students must learn to spell each week that connect with the broader curriculum. If not, be

sure that you select words that include the spelling patterns that you have taught and include words from

the curriculum or other content areas. Always begin the year with more frequently used and regular

word patterns before moving to less frequently used and less regular patterns.

Here are some other general guidelines for spelling instruction:

Review frequently. Improving students’ spelling accuracy requires that you review previously

taught material often. For example, if you are teaching your first graders the vowel consonant e

spelling pattern, you will ask them to spell words that contain that pattern and some soundspelling relationships that they learned earlier in the year. When they blend and write kite, they’ll

be forced to consider why the /k/ sound is spelled with a k and not a c. Revisiting spelling

patterns often keeps them fresh in students’ minds. For the same reason, it is also useful to

provide students with opportunities to analyze and sort words into categories to focus students’

attention on the spelling and letter patterns that they have already learned.

Limit the number of words in one lesson. Expect that students will need to read and work

with words many times before they are able to spell them. To give enough practice with each

word, do not make your lists too long.

Teach students the process of monitoring and checking their spelling. Ask students to

double-check their work for spelling and maintain high expectations for correct spelling of

previously taught words.

Differentiate spelling instruction. For students who experience spelling difficulty, provide

individual or small group instruction to help them hear the sounds in words and connect

those sounds to letters. With a small group of students, you might model how to stretch out

a word and segment it into individual sounds, then use spelling cards or phonics charts to

prompt students for the correct spelling of those sounds. Students with audioprocessing

disorders will struggle to hear the component sounds in a word, so remind them to pay

attention to their mouths as they say the word slowly.

127

Methods of Writing Instruction

Provide immediate feedback. As students transition from inventive to conventional spelling,

be swift and consistent with correcting the spelling of the words that you have already taught.

Do not let students reinforce errors once the word has been taught.

Connect it to their writing. Especially in the upper elementary classroom, drawing a portion

of their spelling words from trends you see in their writing can be very effective and relevant

for them. Older students could even choose some of their own spelling words by scanning

their portfolio for words with which they have trouble.

Don’t carry spelling instruction over into their free writing or drafting. This may only

disrupt the flow of their writing and put undo pressure on them at a time when they should be

concentrating on ideas.

Teach students to spell high frequency words correctly. As mentioned previously, the 100

most common words make up about 50 percent of the material we read. Thus, we can

significantly improve our students’ literacy skills if we teach them to read and spell these

words automatically. So, how does one teach these sight words? In a word, practice. You

simply have to arrange for students to have many, many encounters with these words, both

directly (flashcards, word walls) and indirectly (reading).

One well-established list of these “sight words” from which

teachers might work, is the “Fry list” that we discussed in Chapter

Three. You may find it beneficial to peruse those lists now and

return to them in your classroom so that you can teach them to

your students along-side spelling words. To examine the list, see

“Fry’s 300 Instant Sight Words” in the Elementary Literacy Toolkit

(pp. 34-35) found online at the Resource Exchange on TFANet.

Letter Formation and Handwriting

Most literacy specialists recommend that

lower elementary students have formal

letter formation instruction as part of

their daily routine, even if it is a relatively

short exercise. Students, especially very

young students, need the opportunity to

think about their writing free of concern

for content in order focus attention on

improving handwriting skills.

Most

curricula will have a particular method of

teaching letter formation and handwriting.

Grammar and Mechanics

Research continues to suggest that teaching students to use

correct grammar in spoken and written language improves

their literacy skills substantially. While you may not be

teaching your Kindergarteners the parts of speech, you are—as

part of your strategies to enhance students’ print awareness—modeling, teaching and reinforcing lessons

about

capitalization,

punctuation,

and

other

fundamental mechanics of the writing process.

One book that was particularly engaging for my

students was Punctuation Takes a Vacation. Our

Younger students need to be taught when and how to

class was learning about punctuation in

leave space between sentences, for example. Older

Communication Arts. All of my students also had

students need practice with more complicated

punctuation as an IEP goal. After conducting a

mechanics such as paragraph structure. As students

thorough, interactive read aloud (on three

mature and develop the capacity to think about the

occasions), and creating several independent

various parts of speech in their writing, the mechanics

learning stations based on the material in the book,

lessons can become more complex. While it would

all of my students mastered punctuation. They met

certainly be unwise to completely divorce these

their IEP goals within a fraction of the time allotted.

mechanics lessons from the real writing that students

Allyson Jasper, St. Louis ‘03

are doing, most teachers find that regular “miniManager, Corporate Relations,

lessons” on subjects such as capitalization,

American Academy of Family Physicians

punctuation, or subject-verb agreement are an

important means of learning the basic conventions of

writing. Teachers will often connect a given mini-lesson to a subsequent writing project to allow students

128

to focus on the mechanics or grammar point in their writing. To plan your grammar and language

mechanics instruction, consider the following grade-level benchmarks, from the Mid-continent Research

for Education and Learning:164

Level I (Kindergarten-Second Grades)

Language Arts Benchmarks

Uses conventions of print in writing (e.g.,

forms letters in print, uses upper- and

lowercase letters of the alphabet; spaces

words and sentences; writes from left-towrite and top-to-bottom; includes margins)

Uses complete sentences in written

compositions

Uses nouns in written compositions (e.g.,

nouns for simple objects, family members,

community workers, and categories)

Uses verbs in written compositions (e.g.,

verbs for a variety of situations, action

words)

Uses adjectives in written compositions (i.e.,

uses descriptive words)

Uses adverbs in written compositions (e.g.,

uses words that answer how, when, where,

and why questions)

Uses conventions of capitalization in

written compositions (e.g., first and last

names, first word of a sentence)

Uses conventions of punctuation in written

compositions (e.g., uses periods after

declarative sentences, question marks after

interrogative sentences, uses commas in a

series of words)

Level II (Third-Fifth Grades) Language Arts Benchmarks

Writes in cursive

Uses pronouns in written compositions (e.g., substitutes

pronouns for nouns, uses pronoun agreement)

Uses nouns in written compositions (e.g., uses plural and

singular forms of naming nouns, forms regular and

irregular plural nouns, uses common and proper nouns,

uses nouns as subjects)

Uses verbs in written compositions (e.g., uses a wide

variety of action verbs, past and present verb tenses,

forms of regular verbs, berns that agree with the subject)

Uses adjectives in written compositions (i.e., indefitine,

numerical, predicate adjectives)

Uses adverbs in written compositions (e.g., to make

comparisons)

Uses coordinating conjunctions in written compositions

(e.g., links ideas using connecting ideas)

Uses negatives in written compositions (e.g., avoids

double negatives)

Uses conventions of capitalization in written

compositions (e.g., titles of people; proper nouns [names

of towns, cities, counties, and states; days of the week;

months of the year; names of streets; names of

countries, holidays]; first word of direct quotations;

heading, salutation, and closing of a letter)

Uses conventions of punctuation in written compositions

(e.g., uses periods after imperative sentences and in

initials, abbreviations, and titles before names; uses

commas in dates and addresses and after greetings and

closings in a letter; uses apostrophes in contractions and

possessive nouns; uses quotation marks around titles

and with direct quotations; uses a colon between hour

and minute)

II. Instructional Contexts Along a Continuum of Teacher Directedness

Spelling, grammar, and mechanics make up the building blocks of writing, much the same way

phonemes, graphemes, and morphemes are the building blocks of reading, and dribbling, passing, and

shooting are the building blocks of playing basketball. So when it comes time for students to put those

building block skills to work in an actual “game” situation, you will move students through a continuum of

instructional contexts that can be classified according to a gradual shift from teacher-driven writing to

student-driven writing. Keeping in mind that (1) independent writing is the ultimate goal and (2) the path

along this line for a class of students is anything but linear (as a teacher might use all of the methods in

any given day), consider the following graphic representation of this continuum:

164

http://www.mcrel.org/compendium/standardDetails.asp?subjectID=7&standardID=3, accessed 7/10/2010.

129

Methods of Writing Instruction

Models of Writing

Instruction

Degree of Student Direction

Modeled—Shared—Interactive—Guided—Independent

Degree of Teacher Direction

We will consider each of these five methods in turn.

Modeled Writing—teacher creates, writes, and thinks aloud

Under the modeled writing method, the most teacher-directed approach, the teacher writes in front of

the students, creating the text, and controlling the pen. Even more importantly, the teacher constantly

“thinks aloud” about writing strategies and skills.

This approach allows students to hear the thinking that accompanies the process of writing. Those

thoughts may address choosing a topic, organizing your ideas, using a plan to write your rough draft,

removing repetitive information, or proofreading to fix grammar or spelling mistakes, to name just a few.

For beginning writers who are just developing familiarity with basic book and print awareness, the

modeling teacher might think aloud in the following way:

Let’s see. First, I have to figure out where to start. Do I write from the top going down or

from the bottom going up? I know that I write from the top going down. Now, do I write

from left to right [as teacher makes motion across chalkboard from left to right], or do I

write from right to left? [analogous motion] I know that when I read books, like The Very

Hungry Caterpillar that we read this morning, I read from this side to this side, so I am

going to write from left to right as well . . .

For slightly older students, the thinking aloud might sound more like:

OK. I’ve written in my notebook about the special Wednesday night dinners that my dad

and I had when I was little—our dinner dates. My ideas are really good but they don’t

sound like a story yet. I need to make a plan to help me write a story that other people

will enjoy reading. Hmm… Oh! Now I’m remembering how we read one of Jerdine Nolen’s

stories from In My Momma’s Kitchen. I’m thinking that one thing she did to make us

really love her story was to have everything that happened build up to one really funny

moment. Remember how we all laughed when Daddy sang ‘La Cucaracha’ as his corn

pudding cooked? We called that the ‘hot spot’ in her story, and everything else led us to

that point—the funniest part of all! I think that when I make the plan for my story, I’m

going to tell what happened during our dinner dates and then, at the very end, I’ll share

the best moment of all. My hot spot needs to be something really funny that happened

during one of the dinners, something that will make you all laugh when you read it. Oh, I

see some of you are remembering something funny from my writer’s notebook, and it

looks like you have suggestions for what my hot spot should be… Good idea, guys! I think

I’ll write my story so that all of the events lead up to my dad spilling spaghetti all over his

tie and the waiter bringing him a bib! That’s a perfect hot spot.

130

Thus, by talking aloud about your literacy objectives as you complete the writing, you build your students’

skills, habits, and understanding of a writer’s thought process. As the “modeling teacher,” your role in

this approach as you think aloud is to:

Use expressive language and actions to model critical writing-process concepts

Think aloud about actions and choices in writing

Show students the metacognitive strategies involved in reading and writing

Use modeled writing as a mini-lesson to introduce new writing skills and genres

Demonstrate the importance of composing a meaningful, coherent message for a particular

audience and a specific purpose

Demonstrate the correct use of print conventions such as capitalization, punctuation, and

print directionality

Demonstrate spelling strategies

Connect spelling to phonics lessons

Demonstrate re-reading as a process to help students to remember what they are writing

about

During Modeled Writing, students are listening and watching, with the explicit expectation that they will

be using these strategies on their own at some point soon. Although a standard Modeled Writing lesson

will not last more than 15 minutes, this approach is appropriate for any type of grouping strategy,

including whole class instruction. Many teachers use Modeled Writing exercises each time they

introduce a new writing skill or genre and then transition to the more student-involved approaches

explained below.

Shared Writing—teacher and students co-create; teacher writes and thinks aloud

Shared writing also has the teacher control the pen, but invites the teacher and the students to create the

ideas for the text together. That is, the students and teacher plan out the writing and then the teacher

actually scripts the words. Like in Modeled Writing, it is important that the teacher engage the students

by thinking aloud about the processes that are happening as he or she writes. And, of course, the teacher

may involve students in other ways as well, such as asking them to spell certain words or to decide when

a new paragraph should begin.

This approach effectively reinforces the concepts of print, as the students’ thoughts are transformed to

written language as they watch. In addition to the process-related issues about which teachers might

think aloud during modeled writing, the teacher in a shared writing session may think aloud and talk to

the students more about the content of the writing. Thus, the role of the teacher in Shared Writing is to:

Introduce the lesson or topic by modeling how to begin writing

Plan the text and help students generate ideas for writing

Record students’ ideas

Reinforce print conventions such as capitalization, punctuation, and print directionality

The student, meanwhile, is contributing ideas to the writing and will read and reread the composition with

the teacher. This strategy is also useful for whole group or small group instruction.

Interactive Writing—teacher and students co-create and co-write

For Kindergarten and first grade students, one of the most educationally fruitful learning models is

interactive writing. This approach brings the students into the writing process to create products that are

well beyond the level of anything they could create on their own. The teacher and students share the pen

(or chalk or marker) to do the writing. The teacher plays an active role in monitoring and guiding the

process, talking students through various writing conventions that the group encounters while they write.

131

Methods of Writing Instruction

The purposes of this approach are many. By having a two-way conversation around the creation of words,

sentences, or paragraphs, teachers can negotiate the content of the text, construct words through the

analysis of sound, and develop concepts of letter, word, and punctuation. Moreover, teachers are able to

lead students to increase and reinforce letter knowledge, and gain familiarity with some frequently

encountered words.

Consider the following play-by-play account of an interactive writing activity in a Kindergarten class:

Interactive Writing in Action

The following is a play-by-play description of an Interactive Writing session in the Kindergarten class of Heather

Thompson (Rio Grande Valley ’97) on January 29, 2003. This process took about 8 minutes.

We come back from the park and sit down to write in our class park journal. First, we reread our entries from

previous days. Then, I ask students to think about something they saw or did at the park today. Several hands

shoot up.

Ricky: We saw two dogs!

Vidal: A little dog and a big dog.

Tyler: There was two little dogs.

(An argument ensues about how many dogs there were. Finally it is decided that there were three.)

Teacher: OK, so we’re going to write, wait, let me write the date first. [Writes and reads, “January 29, 2003.”] OK,

we’re going to write, “We saw three dogs.” How many words is that?

We….saw…three…dogs. [Teacher puts a dot on the paper to indicate each word.]

Evelyn: Four words.

Teacher: What do we need to put to start the word “we”?

(Various students chime in with the /w/ sound, some also say the name of the letter.)

Teacher: That’s right! Christina, would you like to come write a capital “w” to start our sentence?

(The teacher similarly elicits the second sound of “we” from the students, and then discusses leaving a space

between the words. Albert comes up to write the first sound of “saw” and writes the “s” backwards.)

Teacher: Oops.

Several students: Backwards!

Teacher: That’s OK. Let’s cover it up with correction tape and try again.

Albert: How, like this? (Writes s in the air, then on the paper.)

Teacher: Now, the sounds in the rest of the word “saw” are hard, but where could we look to find it?

Jenifer: Look on the other paper.

(Teacher and students look at the previous journal to find the word “saw,” then the teacher demonstrates copying

the rest of the word. The teacher then calls another student to write the number 3, and assists the students in

stretching out the word “dogs” to hear and write the letters for all four sounds.)

Teacher: Are we finished?

132

Class: Yes!

Teacher: So, what do we need at the end?

Class: A period!

Teacher: Vanessa, would you like to put the period and draw the three dogs for us so we can remember what we

wrote? Then we will read it one more time.

As you can see from the above description, in the interactive writing model, the teacher’s role is to:

Introduce the lesson by modeling how to begin writing

Plan the text and help students generate ideas for writing

Record students’ ideas, reinforcing print conventions such as capitalization, punctuation, and

print directionality

Reinforce students’ phonemic awareness through writing

Make connections of unknown to known words, such as students’ names

Ask students to participate in the writing at strategic points by asking individuals to write

known letters, words, pieces of punctuation, or phrases

Move your students to independence by requiring them to accept more and more

responsibility in this process

Involve your students in repeatedly reading the products they have created during interactive

writing sessions

As the students provide writing ideas in something like an apprentice role, they are actively engaging in the

writing process, contributing known letters or words at the frontier of their knowledge. The teacher should

be sure to read and reread the ultimate composition, reviewing the skills that have been highlighted in that

process.

As you might imagine, this method is useful for whole class, small group, and individual instruction. Many

Kindergarten and first grade teachers make interactive writing a part of their daily routine.

To summarize, the keys to effective interactive, shared, and modeled writing are that the teacher:

Demonstrate the writing in a way that is large enough that all students in the class or small

group can access it and be involved

Think aloud constantly about what is being written

Remind students to use the skills and strategies that you model when they write independently

Involve ALL students (There is a risk with this model that one student will be participating

while all others are off task.)

Guided Writing—students create and write in small groups while the teacher guides the process

In Guided Writing, the teacher works with the whole class or a small group of students who have similar needs

and coaches them as they write a composition. Here, the students take on the actual drafting responsibilities

as the teacher presents a structured lesson that guides the students through the writing process. The teacher

closely supervises the students, an element that makes this model most appropriate for small groups. Guided

writing gives each student the opportunity to produce his or her own writing, with a bit of teacher support. This

approach is often used to teach a specific writing procedure, strategy, or skill.

133

Methods of Writing Instruction

In this approach, the role of the teacher is to:

Observe and assess students’ writing

Meet with individuals or small groups who have similar needs

Actively prompt, coach, and guide individual students’ writing skills

Respond as a reader

Ask open-ended questions

Extend students’ thinking in the process of composing

Foster writing independence

Independent Writing—students create and write while the teacher confers and monitors progress

The student is in charge of the drafting under an independent writing model. Students use the writing

process to write sentences, paragraphs, stories, or essays. The teacher monitors students’ progress and

intervenes appropriately. This model can be implemented in any number of ways, including writing

centers, writing workshops, journal writing, and letter writing.

Do not misinterpret the name of this approach as implying that the teacher is not involved. The teacher

continues to be involved—by creating opportunities to engage in authentic, purposeful writing, by

responding to the content of students’ writing, and by assisting students with the revision and editing

process. The student’s role does grow under this model, as he or she takes a larger ownership of both

the process and the product. The student might select topics and content, or even genre in some cases.

Eventually, the student should be responsible for his or her own revision and editing, as well.

Review of Part II

Method

Modeled

Writing

Summary

Teacher creates,

writes, and thinks

aloud.

Shared

Writing

Interactive

Writing

Teacher and

students co-create;

teacher writes and

thinks aloud.

Teacher and

students co-create

and co-write.

Guided

Writing

Independent

Writing

134

Students create

and write while

teacher closely

monitors and

guides process.

Students create

and write while

teacher monitors

progress.

Tips and Suggestions

Think aloud constantly, explaining the strategies you use.

Use expressive language and actions to describe exactly what you’re

doing.

Use modeled writing as a mini-lesson to introduce new writing skills

and genres.

Have your students watch as you transform their thoughts into written

words.

Contribute ideas to the writing, but help students generate ideas

themselves.

Talk, think aloud, and involve your students while one or more write.

Have a two-way conversation around the creation of words, sentences, or

paragraphs.

Move your students to independence by not doing what they can do for

themselves.

Demonstrate the writing in a way that is large enough that all students in

the class can access it and be involved.

Work with the whole class or a small group of students who have

similar needs as they write a composition.

Observe and assess your students’ writing, actively coaching their

skills.

Ask open-ended questions to extend your students’ thinking in the

process.

Intervene with the writing process only when appropriate.

Continue to be involved, but let the students’ role grow.

Respond to the content of your students’ writing.

Assist students with the revision and editing process.

III. The Writing Process: Pre-Writing, Drafting, Revising, Editing, and Publishing

The final way that we can think about the task of writing instruction is by considering how you might

approach instructing students to create a particular written product. The most effective approach to

writing any particular text, be it a paragraph, letter, essay, short story, or research project, requires the

writer to break the process into five steps:

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

Pre-writing

Drafting

Revising

Proofreading and Editing

Publishing and Presentation

As a strong literacy instructor, you will be teaching

students both how to implement strategies for each

of these steps, and the sequence of these steps

themselves. That is, you want your students to

associate the concept of writing with this complete

process. It should be second nature to your students

that there is a meaningful pre-writing stage of any

writing project, and that there is a crucial revising

stage to any writing project. At the same time, your

students should have command of a range of

strategies to use within each stage of the process. In

this section, we will consider various strategies that

you will teach your students to help them at each

stage of the writing process.

At the beginning of the year, I read Amelia’s

Notebook (a story of a young girl who keeps her own

journal) as a way of motivating my students to write.

They then decorate their own notebooks that they will

use all year. Inside these notebooks we complete our

pre-writing steps for each project (our lists of seed

ideas, quick writes, wonderings, etc.). We also have

writing folders that hold work from each stage of the

process (drafts, revisions, and final drafts) for each

individual project.

Shannen Coleman, Baltimore ‘03

Academic Director, Child First Authority/BUILD

Note that our focus in this chapter will be on writing both as a process and a product. Traditionally,

classroom writing instruction has focused on writing products (sentences, paragraphs, essays, research

papers, etc.), with little regard for process. For example, students might be expected to write an essay

based only on their review of models of an essay. In the last two decades, however, we have seen

significant changes in the way schools approach writing instruction. The most effective approach involves

more attention to instructional activities that lead students to think through and organize their thoughts

before writing and to re-think and revise their initial drafts.165 So, while today we still emphasize the

importance of the final product, we recognize that we must also focus on the process itself, expressly

teaching students the steps that go into writing. These trends have led to our focus on the five-step

writing process of pre-writing, drafting, revising, editing and publishing.

Pre-Writing

Pre-writing is arguably the most consequential step in the writing process, and it’s importance is often

overlooked by teachers and students. Many elementary students think that “writing” a story or paper

means sitting down and creating something that will not be altered. While it takes somewhat different

forms depending on grade and developmental levels, pre-writing is both a discovery stage, when content

and ideas are being collected and organized, and a rehearsal stage, when writers are mentally, verbally,

and on paper “trying out” different topics about which they might write. Among the many forms that prewriting can take are:

165

Smith, Carl. “Writing Instruction: Changing Views over the Years,” ERIC Clearinghouse on Reading, English, and

Communication Digest, #155.

135

Methods of Writing Instruction

Generating Words and Ideas Exercises. Motivate students to start thinking about words and

the subject that will be written about, such as:

- Brainstorming

- Listing

- Observing/taking notes

- Reading and conducting research/taking notes

- Free writing

- Sentence frames (My favorite place is…)

Organization. All students need to be taught how to organize their ideas before they write a

first draft. Graphic organizers and outlines are excellent tools for pre-writing, as they force

students to think about connections and relationships between ideas. You can teach students

to create a plan before they write, either by using a teacher-created organizer or a studentcreated outline. For some examples of graphic organizers, see the Instructional Planning &

Delivery text.

Previewing Grammar and Mechanics. Previewing a specific grammar skill that you want

students to use in their writing will give them an immediate understanding of your

expectations, as well as the necessary time to practice the skill in isolation. For example, if

your students are about to write a narrative with dialogue, you could take that opportunity to

teach a mini-lesson on the use of quotation marks.

Teaching Characteristics of Particular

Forms/Genres. A critical stage in the prewriting process is instruction in the genre of

writing students will be producing. As you

can imagine, you cannot expect students to

write a persuasive letter, a personal

narrative, or an expository article with any

success if they do not know the

characteristics of a piece of writing in that

genre and have not read or examined

exemplary models. Just as when you are

teaching any other skill, when teaching the

skill of writing in a particular genre, explain

the characteristics of the genre, look at

several exemplary models to identify those

characteristics, model the creation of a

piece in the genre, and then have students

apply the characteristics of the genre as

they draft their own piece.

KWL Chart

A useful tool to help students pre-write an

informational piece is the “KWL Plus Chart.” As

you know from our previous discussions of this

model, “KWL” stands for “know, want to know,

learn.” Before beginning a project, students can

record what they know about the topic and what

they want to know. As they research, they write

what they’ve learned. The “plus” feature allows

students to sort all that they know about the topic

into categories. Though students need a different

structure (an outline, perhaps) to help them

organize this information, KWL charts help them

take notes as they research. For a sample KWL

chart, see the Elementary Literacy Toolkit (p. 52)

found online at the Resource Exchange on

TFANet.

For an example of student work in the pre-writing stage, see the Elementary Literacy Toolkit (pp. 53-54:

“Sample Student Work: Pre-Writing”); this Toolkit can be found online at the Resource Exchange on

TFANet.

136

Drafting

Once students know the characteristics of the genre and

have collected and organized their ideas, they are ready

to work in the second stage of writing. Drafting refers to

the time when the student is actually crafting language

and translating an outline or plan into a more coherent

piece. Part of your role as a teacher of literacy will be to

disabuse your students of the idea that drafting is

writing. Rather, drafting is one step in the writing

process. The first draft is usually done relatively quickly

to get ideas on paper. In fact, research indicates that

writers who try to make the first draft “perfect” run the

risk of missing opportunities to discover ideas that could

be surfacing during the drafting process.166

Young writers need quiet and focused atmospheres that

will be conducive to drafting. Create routines that get

all distractions (sharpening pencils, gathering

materials, etc.) out of the way before writing time

begins. Many teachers, for example, use a routine

called Writers’ Workshop when students are working in

the stages of the writing process and the teacher is

having writing conferences with individual students

about their progress. For an example of student work in

the drafting stage, see “Sample Student Work: Drafting”

in the online Elementary Literacy Toolkit (pp. 55-56).

How Do I Choose (and Help Students Choose)

Topics for Writing?

One of your goals is to help students learn to write

for a variety of purposes and in a variety of forms.

For example, students can write personal

narratives, short stories, poetry, persuasive

letters or essays, step-by-step directions, or

informational pamphlets and reports. When you

are choosing topics for students to write about,

consider the following guidelines:

Start with topics that are familiar and

manageable for the students you are

teaching. First graders will be able to write

step-by-step directions for cooking a

Thanksgiving turkey (though they may be less

than accurate!) but will not have the requisite

knowledge and skills to write an expository

essay explaining the origins of common

holiday traditions.

Teach students to write the types of genres

that they are reading. Kindergarteners who

are reading and listening to classroom rules

can “write” and illustrate rules for the

cafeteria. Third graders engaged in a study of

nonfiction can write an expository article for a

class magazine (perhaps relating to a science

unit). Fifth graders who are reading and

listening to memoirs can create personal

narratives.

Provide opportunities for choice, in order to

build ownership and motivate students. If you

have decided that your third graders will

create a magazine that gives other students

information about Earth/Space science, allow

them to choose a topic on which to write their

particular article (erosion, fossils, or

continental and oceanic features).

Revising

Revising refers to those substantive changes that are

made after the rough draft. Primarily, this stage

considers the effectiveness of a piece, both in terms of

content and language. Revision does not focus on

mechanics, a task that makes up the editing and

proofreading stage. To help young students understand

the difference, you might explain that writers focus on

how their piece sounds during the revising stage and

how it looks during editing. While this description is not

perfect, it is often a helpful distinction for beginning writers.

Possible foci during the revision stage of writing are the ideas and content, the organization and “flow,”

and the language choices made in the piece. Of course, the extent to which students revise a written

piece depends partially on their developmental level. For example, while you might teach first graders

simply to delete ideas that are off topic, you will probably expect upper elementary students to revise

more extensively, perhaps by adding descriptive language, clarifying sections that are unclear, including

transition words and sentences, or changing the order in which ideas are presented.

Botel, M. and Susan Lytle. Pennsylvania Comprehensive Reading/Communication Arts Plan II. Harrisburg, PA:

Pennsylvania Department of Education – Communications Division, 1998.

166

137

Methods of Writing Instruction

Elementary students find revising to be a particularly

challenging step in the writing process. As with instruction

in all stages, you should deliver a whole-group mini-lesson

on a revision topic, and then model revising your own piece

for your students. You might consider one of the following

sample topics, depending on the skills that your students

need to develop:

Varying sentence structure

Elaborating on ideas

Creating strong topic sentences

Consistency of voice, character, or style

Organization of ideas

Improving introductions/story beginnings

Adding sensory details

Including time and transition words

Using dialogue

Choosing strong action verbs

Crafting conclusions/story endings

When students have a conference with me

during the revising and editing stages, it’s sort

of a “DMV” system: a student takes a

clothespin with a number on it and goes back

to his or her desk to continue working on his

or her story, or he or she can start a new

story. I call a number, and whoever has that

number gets to come to the back table with

their story, and I can help him or her revise

and edit it. This really cuts down on

congestion around my table!

Brooke McCaffrey, Phoenix ‘02

Kindergarten Teacher,

Prospect Hills Academy Charter School

Additionally, students need varying amounts of feedback from you and their peers as they attempt to revise

their first drafts. Teachers of Kindergarten through third graders, as well as fourth and fifth teachers whose

students are just beginning to use the writing process, need to provide a good deal of structure during the

revision process. One way that you might provide structure is by literally “cutting and pasting” students’ first

drafts (mimicking the word processing function on a computer), opening up space for students to add

details or helping them to rearrange the order in which they express their ideas.

Proofreading and Editing

During the proofreading and editing phase, the student-author does the nitty-gritty check on the mechanics

of the writing, watching carefully for details such as punctuation, spelling, and grammar. These editing

skills must be taught to even our youngest students. Children should leave your room not only

commanding age-appropriate proofreading and editing skills, but believing that this stage is an integral part

of writing that cannot be skipped.

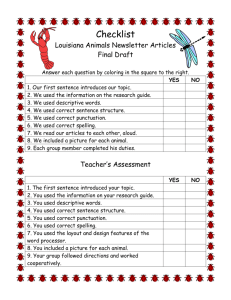

Teaching this part of the writing process can be accomplished through presenting mini-lessons on

capitalization, punctuation, etc. and through providing a checklist of language mechanics expectations for the

text. It is also taught through teachers’ modeling during modeled writing, shared writing, or interactive

writing. See “Age-Appropriate Proofreading Checklists”

in the Elementary Literacy Toolkit (p. 57) found online

Checklists are an excellent way of making your

at the Resource Exchange on TFANet. A table of

expectations clear and helping your students revise

“Proofreading Marks” that shows the grades in which

and edit their work. I make a checklist for each writing

piece that we complete, and give it to the students

various proofreading marks are first used is also

during the revision part of the process. As they revise

provided in the Toolkit (p. 58).

and edit, they can refer back to what I am looking for

(which I’ve taught in mini-lessons). When I grade the

assignment, I fill in the checklist and calculate the

grade based on how many checks the child receives).

Jessica Wells Cantiello, New York ‘03

PhD Candidate, The Graduate Center of the City

University of New York (CUNY)

138

Publication and Presentation

This stage brings closure to the writing process by

allowing students to share their best work with others,

whether that sharing takes the form of a book that is

sold at local bookstores or an oral presentation about

a written project to the class. Many teachers report

that the possibility of publication, in its many forms, has a significant impact on a students’ motivation to

write and also focuses students’ energy on revising and editing.

There are obviously many ways to publish students’ writing. To spark your own thoughts, consider the

following methods:

read writing aloud

submit to a contest

create a class anthology

record on a cassette tape

send it to a pen pal

submit it to a magazine

read it at an assembly

share in a reading party

share with family

hold an “author’s tea”

display on bulletin board

make a hard-bound book

make a big book

share with younger students

The Elementary Literacy Toolkit (available online at the Resource Exchange on TFANet) contains directions

for making bound books (p. 59: “Binding Books for the Classroom”) and also an example of student work

in the publishing stage (pp. 60-63: “Sample Student Work: Publishing”).

Review of Part III

Thus, when we think carefully about the writing process itself—pre-writing, drafting, revising, editing, and

publishing—we uncover a whole menu of activities and strategies that will help us improve our students’

literacy skills. During pre-writing, for example, we can teach vocabulary and organizational techniques.

During the editing process, we can focus students’ attention on particular grammar skills. Combined

with the various contexts for teaching writing that span the continuum of teacher-directedness, these

strategies create powerful tools for literacy instruction.

Stage

Pre-Writing

Review

Teacher leads children to

generate and organize

content and ideas before

beginning to write.

Drafting

Student crafts the

language.

Revising

Proofreading

and Editing

Publishing and

Presentation

Student (often with

teacher’s guidance)

makes substantive

changes to draft, including

fixing content and style.

Student checks the

mechanics of the writing,

watching carefully for

punctuation, spelling and

other mechanics.

Allow students to share

their best work with

others in various ways.

Tips and Suggestions

Ask students to free write in a notebook to spur ideas.

Teach students to read and take notes.

Enable students to organize ideas through the use of graphic

organizers.

Use exemplary models to teach characteristics of the genre.

Preview a grammar skill to make students comfortable with

using it in their writing.

Teach your students that drafting is not writing, just one step

of the writing process.

Provide a quiet and focused atmosphere with set routines and

procedures.

Note: this step does not focus on mechanics; that will be

addressed in the next stage.

Encourage students to improve their word choice, change the

organization of ideas, or ensure sufficient evidence is provided

to support a claim.

Teach these editing skills, even to very young children.

Present mini-lessons on capitalization, punctuation, etc.

Provide a checklist of language mechanics expectations to

your students during this stage.

A few ways to “publish” your students’ writing:

Read the writing aloud.

Invite others to hear student-authors read their published

work.

Submit the piece to a contest or magazine.

Make a book.

139

Methods of Writing Instruction

Conclusion

This chapter has focused on methods of writing instruction:

In Part I, we considered some of the basic building blocks of writing that we know form a critically

important foundation for literacy development.

In Part II, we considered the various teacher- and student-centered modes of writing, including

techniques such as Shared Writing and Interactive Writing.

Finally, in Part III, we considered the various stages of the writing process that students use to create

their own written products. As you read, each stage of the writing process—pre-writing, drafting,

revising, editing, and publishing—offers a range of educational opportunities for teachers and

students.

140