California Essential Habitat Connectivity Project

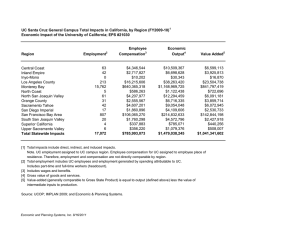

advertisement