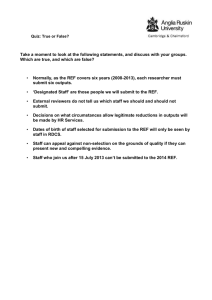

The Research Excellence Framework (REF) UCU Survey Report

advertisement