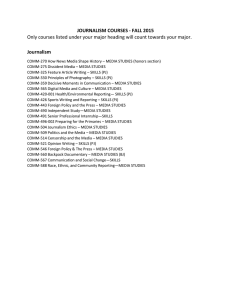

The Future of Journalism

advertisement